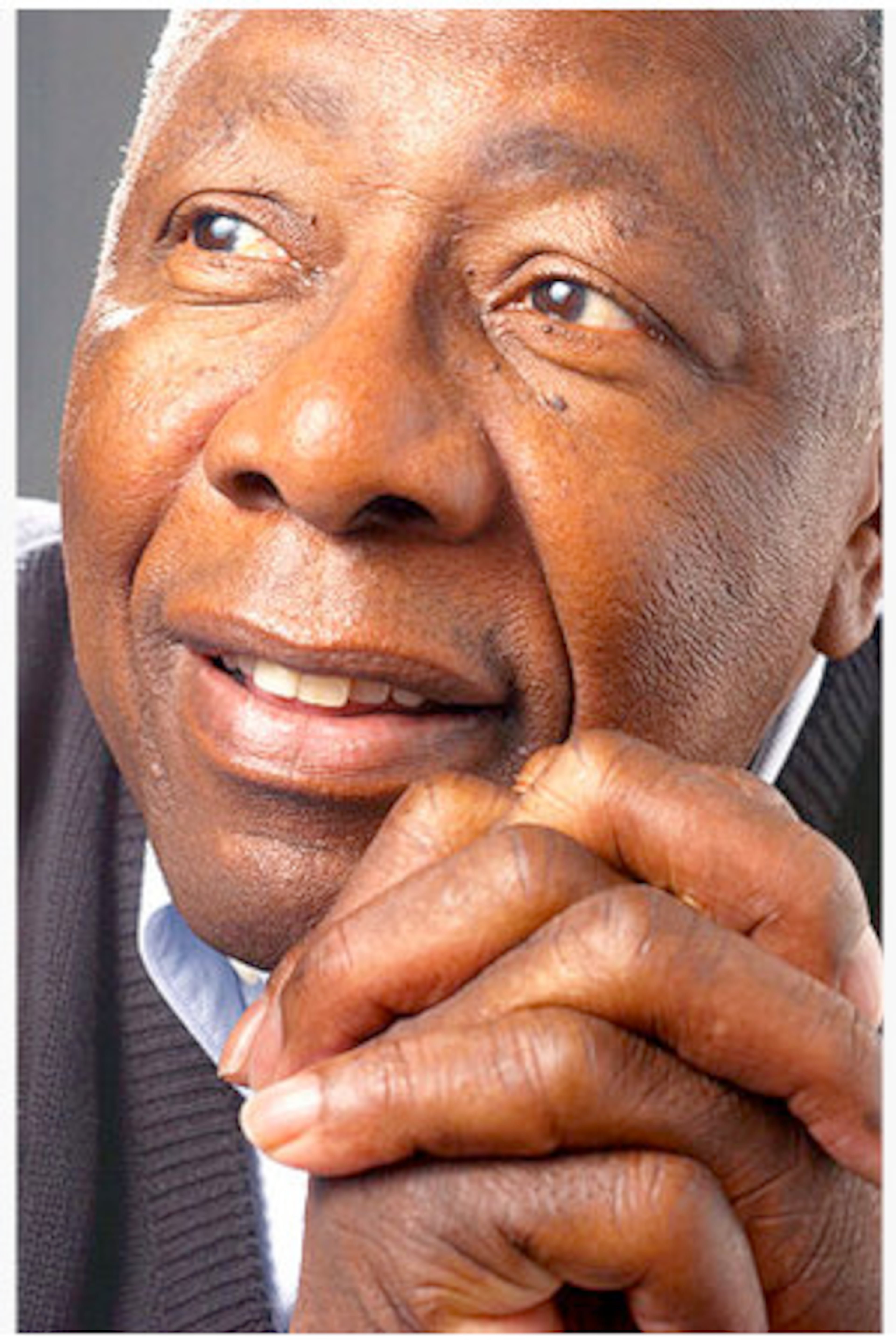

Baseball great Henry ‘Hank’ Aaron, 86, passes into history

In March of 1954, with his place in the major leagues far from assured, Hank Aaron was granted a start in a Milwaukee exhibition game versus Boston, only because Bobby Thomson, the regular left fielder and Aaron’s idol, had just broken his ankle.

Already possessed of dramatic timing at the age of 20, the rookie promptly drilled a ball that carried the wall, flew over a row of trailers parked outside the Sarasota park and reverberated so loudly in the Red Sox clubhouse that the great Ted Williams emerged, as Aaron recalled, “wanting to know who it was that could make a bat sound that way when it hit a baseball.”

Over the next 23 years, a nation of fans would join in Williams' wonder, as Aaron was transformed from a raw, cross-handed line-drive hitter into the game’s most prolific force. A Hall of Famer, Atlanta’s first professional sports star, and, in a soft-spoken way, an agent of change in the post-Jim Crow South, Aaron came to embody the city as he embodied the Braves.

Aaron, at one time baseball’s all-time home run king, died Friday at the age of 86.

“We are absolutely devastated by the passing of our beloved Hank,” Braves Chairman Terry McGuirk said in a statement released by the team. “He was a beacon for our organization first as a player, then with player development, and always with our community efforts. His incredible talent and resolve helped him achieve the highest accomplishments, yet he never lost his humble nature. Henry Louis Aaron wasn’t just our icon, but one across Major League Baseball and around the world. His success on the diamond was matched only by his business accomplishments off the field and capped by his extraordinary philanthropic efforts.

“We are heartbroken and thinking of his wife Billye and their children Gaile, Hank, Jr., Lary, Dorinda and Ceci and his grandchildren.”

According to the Braves, Aaron passed away peacefully in his sleep.

Aaron told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2006: “I don’t think too many people got a chance to know me through the years, and that was something that was my own doing, because I’m actually kind of a loner, a guy that has stayed to himself”

“A lot of people thought they knew me, but they really didn’t.”

“They pretend that they know me, but I travel alone. I do just about everything alone. I have associates, but I don’t have many friends. I would just want to be remembered as somebody who just tried to be fair with people.”

In a funhouse way, Aaron could be viewed differently from varying angles. To a 19-year-old kid breaking in with the Braves in 1968, Aaron was not a star, but an “extra parent.”

“I’ve always loved the guy,” said Dusty Baker, an Aaron teammate for eight years long before he became a three-time National League manager of the year. “He’d cut those eyes at you, and you knew you had to straighten up and stop doing wrong. He was always full of honor and dignity.”

Bud Selig said that though he and Aaron had little in common, they forged a life-long friendship because of their love of baseball.

“He’s just been held with such reverence by everybody,” said Selig, who in 1999 established the Hank Aaron Award for the yearly offensive leader in both the National and American Leagues. “He got over all of that horrible, horrible hatred of the 1970s when he was breaking Babe Ruth’s [career homerun] record, and he was so classy and so dignified through it all and afterward. I run into people who don’t know him as well as I do, and they just say, ‘Wow, what a wonderful person.’”

To a refugee of the Ohio coal fields, he was a man of amazing grace.

“I never saw him angry,” said Hall of Famer Phil Niekro, who recently died and broke in with the Braves in 1964 and was Aaron’s teammate for 11 seasons. “I never even saw the man get upset. I’m sure it had to have happened, but if he ever was angry, he kept it to himself.”

Aaron’s record of 755 home runs hardly does justice to his extraordinary career, for he retired with 23 major league records. The all-time RBI leader (2,297) also racked up the most extra-base hits (1,477) and finished in the top three for at-bats (second with 12,364), runs (second with 2,174 in a tie with Babe Ruth), games (third with 3,298) and hits (third with 3,771).

Yet for such slugging, he averaged only 63 strikeouts per season and retired with a career .305 batting average. A 20-time All-Star, he won the 1957 NL Most Valuable Player award and was rushed to Cooperstown on the first-ballot in 1982.

His magnificent wrists became a thing of legend.

“There always was a great comparison between Willie Mays and Hank Aaron,” Ernie Johnson, a former Braves teammate before moving to the broadcast booth once said. “I think a Los Angeles writer said it best when we were playing out there, and the guy wrote, ‘Hank Aaron does everything that Willie Mays does, but his cap doesn’t fall off.’”

Yet what Mays could not do and what the typical contemporary player declines to do, is shoulder civic responsibility. An African-American presence in a majority African-American city during the 1960s, Aaron did not flee from the prospect of societal change.

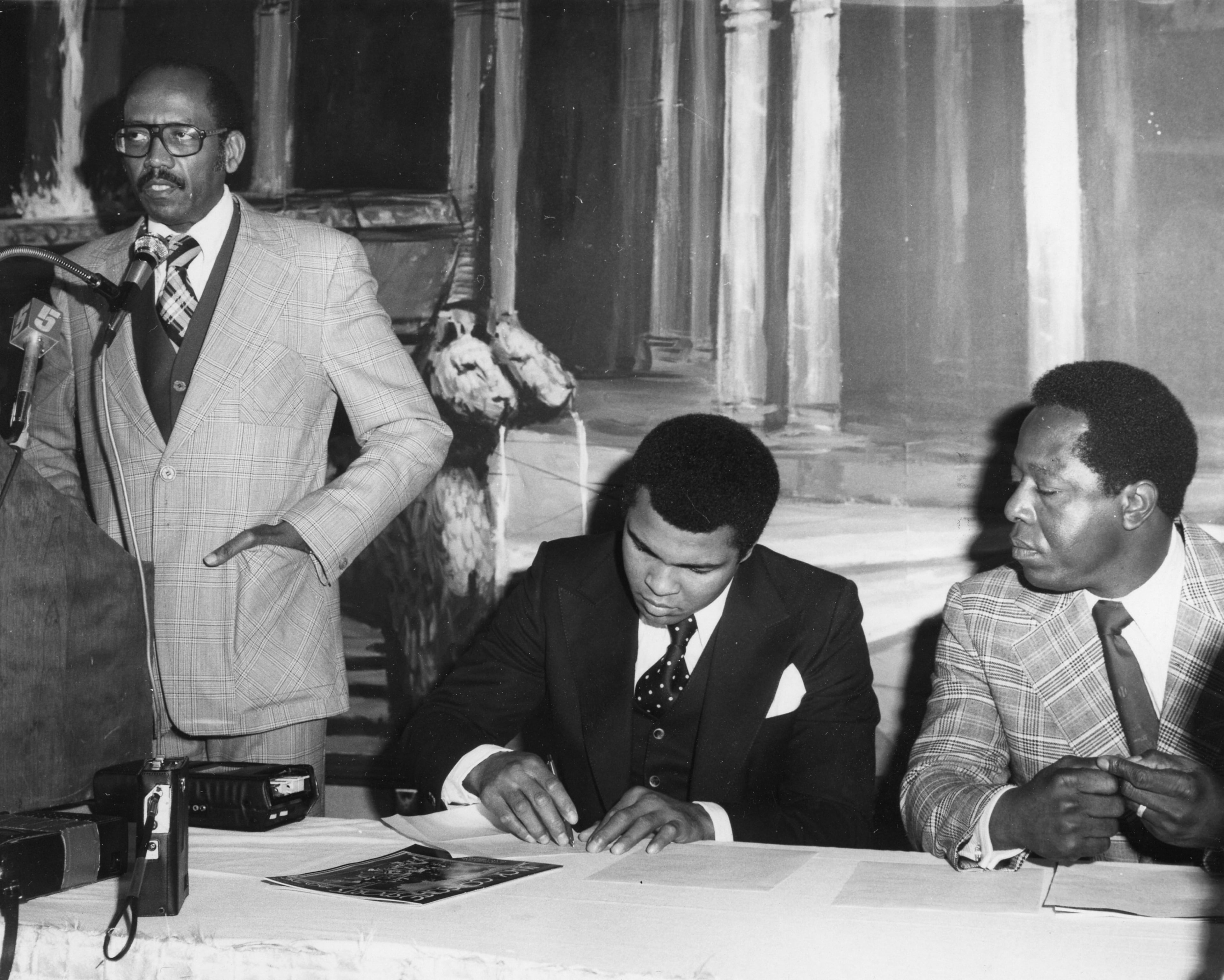

“I was standing there when the parade with the Braves came into town [from Milwaukee],” said two-time Atlanta mayor Andrew Young, recalled of a 1966 welcoming celebration. “There were some of the good old boys standing there with me, and I was sort of wondering what they would say, because he came in, sitting on the back of a convertible. And they said to each other, ‘You know, we’re a big-league town now, and that fella oughtta be able to buy a house wherever he wants to.’ "

Though he had come to the game seven years after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier, Aaron was in the first wave of new Black stars, many of them from the Deep South. Like Aaron, Mays, Willie McCovey and Billy Williams all came from Alabama and all broke into the majors in the 1950s. Only Aaron would stay in the South.

“His coming here opened up the town significantly,” Young said. “That actually was (then-mayor) Ivan Allen’s plan, that big-league sports would bring a big-league attitude to the city of Atlanta. And it was right about that time that we started the campaign of ‘the city too busy to hate.’ So I’ve always said that Hank Aaron made a huge contribution to the successful desegregation of Atlanta. He did so very quietly and very effectively.”

Born into poverty Feb. 5, 1934, in segregated Mobile, Henry Louis Aaron was the third child of Herbert and Estella Aaron. In high school, he mostly played softball.

Aaron never totally abandoned his oldest habits, even while ascending in the corporate ranks in Ted Turner’s old empire, and later as a successful car dealer. He was prone to fry fish and eat it on the porch of his southwest Atlanta home. A life-long Cleveland Browns fan, he occasionally would fly to northern Ohio on game days and sneak into the old Dawg Pound in disguise to watch his team play.

But Aaron’s connection with one number — No. 715 — would bear no disguising. It was the homerun that surpassed Ruth’s all-time total of 714. It marked Aaron forever, for better and for worse. And if he were to need any refreshing of his dark memories of his relationship with breaking Ruth’s record, he only needed to climb the stairs to his attic, where he kept a box of the worst of his hate mail, filled the worst racial epithets people could conceive to spit at him.

“Since I was so close to Hank, I had to look at a lot of that stuff,” Baker said. “It was terrible, but he was still carrying himself with honor and dignity. He treated white kids and Latin kids as well as he did the Black kids. He treated everybody good, regardless. That’s why it bothers me when I hear people say, ‘Well, Hank was bitter.’

“And if he had any bitterness, which I didn’t really see, he had plenty of reason to be, brother. You hear what I’m telling you?”

In an interview for the 20th anniversary of No. 715, Aaron acknowledged the split public image: the smiling baseball ambassador who never tossed his hate letters.

“A lot of people still don’t understand me,” Aaron said. "Some of them view me as a very bitter person. Some of them look and say he’s very angry. And those things are not true. I’ve tried to tell people that. I don’t have time to be angry or bitter. I may have been bitter right after I got out of baseball, but that’s all gone by the wayside. I don’t have time for things like that. …

“Somebody asked me if baseball was good to me. I was as good to baseball as baseball was to me. I think I was better to baseball than baseball was to me. But my life has moved up to another level.”

As with so many baseball careers, it almost never happened. Aaron nearly baled out before ever reaching the majors. In 1952, the Braves signed the skinny second baseman away from the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League for $10,000. Playing 87 games (.336, 61 RBIs) for Eau Claire, Aaron was recognized as the Class A Northern League rookie of the year.

But then came 1953, when the Braves shipped Aaron to Jacksonville, where he was forced to battle more than just breaking pitches and runners sliding spikes high into second base. As one of the first Black players in the Class A South Atlantic League, Aaron saw Jim Crow from a more sinister angle, his white teammates afforded meals and lodging he never saw. One night, a guard fired a gun at him when he returned to training camp after hours.

Still, the stats never wavered; he hit .362 that season as the Sally League’s MVP. Ticketed in 1954 for the Class AA Atlanta Crackers, his spring plans changed when Thomson, hero of the 1951 New York Giants, broke his ankle shortly after being traded to the Braves.

Thomson would return to play, but he would never get his job back. A month after Ted Williams wondered what that big noise in Sarasota was, Aaron was in the majors to stay.

“I just thought I was way out of my league. I mean, it was like a strange dream: Is this really happening?” Aaron said. “Here I was with the Braves in the company of supermen all of a sudden. I really had no idea that I would halfway reach anything near the point in baseball that I had gotten to back then.”

Future Hall of Famer Eddie Mathews was among Aaron’s new teammates, but that didn’t intimidate the rookie.

“He’d only been in the league a few years, and he didn’t have a name,” Aaron said. “Joe Adcock didn’t have a name. Johnny Logan didn’t have a name. Del Crandall didn’t have a name.”

But Warren Spahn had a name — and the club ace, a 33-year-old World War II veteran, would make Aaron doubt his worth. Aaron recalled how Spahn used to join Adcock in uttering racially charged comments in the clubhouse.

The Braves’ first game during his rookie year was in Cincinnati, the home of baseball’s first professional team. It is a proud city that always treats opening day as a religious holiday, and such was the case on April 13, 1954. There was the traditionally loud and colorful parade that moved through downtown to an absolutely stuffed Crosley Field. And, before long, there was Aaron, walking to home plate for his first time in the majors to face the Reds’ Joe Nuxhall. With parts of the overflow crowd literally standing around the outfield, and with his heart skipping more than a few beats, the rookie contemplated making a U-turn back to Mobile.

“I was scared. I was scared. I was scared,” said Aaron. He barely had enough strength in his wobbly legs to chase fly balls in left field, he said. And he was a disaster in the batter’s box. Despite a slugfest, featuring prolific hitting from both teams, Aaron went 0-for-5.

“I hadn’t been overly shocked playing in Jacksonville, but I just thought there was no way that yours truly should be playing with the guys that I was playing with,” he said.

This, in effect, was a downside to Robinson’s entry in Brooklyn. As teams now scoured the countryside for Black prospects, Aaron was among a host of young players who may have arrived before their time.

“Baseball back in those days had not caught on with Black kids,” Aaron said. “Television wasn’t prevalent. The only way you could keep up with it was through radio, and the only somebody that you kept up with was the Dodgers, especially among Black people.

“Although I finally was a player in the majors, the only guys I knew about was Jackie, Campy [Roy Campanella], Don Newcombe and those guys. I didn’t know about anybody on the Cincinnati team.”

It showed. Not until the Braves returned for their home opener did Aaron get his first hit, a double off St. Louis' Vic Raschi. Eight days after that, Aaron faced Raschi in St. Louis to slam the first of what would become 755 home runs.

“I don’t think I ever got to the point during that season of feeling comfortable,” Aaron said, adding, “I always was scared, and I always kept one bag halfway packed, knowing that, if things didn’t work out, they were going to send me be back in Triple-A ball. And that was the way baseball was played back then. You had to really show them something to stick around. It just so happened that they really didn’t have anybody else to play out there but me.”

Not even a broken ankle in early September could budge him from the Milwaukee roster now. He hit .280, which amazingly would be his lowest seasonal average until he hit .279 in 1966. It also would be the only season in which he would play less than 145 games until 1971. He finished with 13 home runs, which would be the only time he would manage less than 20 home runs in a season for the next two decades.

There also were two dramatic switches for Aaron after his first season. He moved from left to right field, where he would become a three-time Gold Glove winner, and he shed his No. 5 to become linked with No. 44 for eternity.

“He didn’t weigh very much, maybe 175 or 180 pounds,” said Johnson. “We just wondered how he would get all of that bat speed until you saw his forearms. He didn’t make hitting very scientific. I remember one time somebody asked him how he hits like that. He said, ‘Well, two things. I look for the ball and I hit it.’ "

Johnson recalled times he would fume over the treatment of Aaron and other Black players into the early 1960s.

“We were playing a game in spring training, and afterward, we pulled up to a restaurant,” Johnson said. “The guys were starved, and the owner came out as we got off the bus, and the owner said, ‘I’m sorry, but the Black players are going to have to eat in the kitchen.’

“Charlie Grimm, our manager, turns, looks at us and says, ‘About face. Let’s get back on the bus. We all eat together.’ Hank ran into those things a lot during that time, but he always could handle those things.”

With Milwaukee appearing in back-to-back World Series in 1957 and 1958, splitting the two with the New York Yankees, stardom came easily to Aaron. He quietly strung together four 40-plus home run seasons over seven years (1957-63) and his total stood at 398 when the team moved to Georgia, where Atlanta-Fulton County quickly earned its nickname, The Launching Pad.

Where the Great Bambino had created his record with a New York-hyped flair, Hammerin' Hank did so in a small market, quietly chipping away at the game’s most prized mark, which had stood since 1935.

He never finished with more than 47 home runs in a season (1971) — an Atlanta record that lasted until Andruw Jones’ 51 in 2005. But Aaron had eight seasons with 40 or more home runs, the last coming in 1973, when he finished the year with 713 homers and an estimated 930,000 pieces of mail. Much of it was racist. There also were enough death threats for the FBI to get involved. Aaron received personal protection through the off-season.

As interest bubbled over in the first week of the 1974 season, Aaron homered off the Reds' Jack Billingham, 20 years to the date and in the same city as his debut. Mathews, then Braves manager, decided to rest his 40-year-old star for the next two games before the Braves went home for their Atlanta opener.

Mathews took a media whipping for the decision, which was seen as a plot to stage history in Atlanta, and after Aaron sat out the second game, baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn forced Mathews to start Aaron in Game 3 “in the best interest of baseball.”

But Aaron eventually went hitless, setting up his date with history the following night at soggy Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium before national television cameras and celebrities. Pearl Bailey sang “The National Anthem.” Sammy Davis Jr. was in the stands, and so was Gov. Jimmy Carter. Aaron’s parents, Herbert and Estella, made the trip from Mobile to help swell the rocking and rolling ballpark to beyond 54,000.

The moment came in the fourth inning. After Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Al Downing threw a low slider toward the middle of the plate, Aaron carved another of his economical swings and watched the ball land over the fence in left-center field. He glided around the bases despite two young fans jumping in his way. He was met at home plate by a mob that included his mother, and a large smile eased across his normally stoic face. He was just relieved that it was over.

During his AJC interview in 2006, Aaron recalled the moment with a renewed sense of pride.

“Really, I’m not as in awe of the moment as I used to be,” Aaron said. “It’s to the point where I look back and I think to myself that I played the game the way that I wanted to play it for 23 years. Instead of 755 home runs, I could have ended up with 775 or more, if I would have really pushed myself during the end of my career.”

Sign Hank Aaron’s guestbook here on ajc.com

Then pausing, Aaron added what he wanted to say the most about his journey as a player from Mobile to Indianapolis to Eau Claire to Jacksonville to Milwaukee to Atlanta and to immortality: “Yeah, I did hit a lot of home runs, but I never struck out 100 times in a season. That’s the thing that I marvel at more than anything I did in the game.”

Aaron retired before the 1977 season, spending the last two years of his career as a faded star for Selig’s Brewers. He was 42 when he finished playing, but he was far from finished with baseball. With Jackie Robinson’s death in 1972, Black players had lost their loudest voice and Aaron was not reluctant to criticize what he saw as remaining inequities in the game.

Aaron mentioned back then how the game was hesitant to hire African-Americans for coaching, managing and executive jobs. He even chastised baseball for refusing to consider him as a candidate for commissioner after Kuhn, his old nemesis, retired in 1984.

Young chastised those who believe Aaron went from soft-spoken to outspoken over night. Young credits him with helping his successful bid to become Georgia’s U.S. congressman in 1973, when Aaron not only contributed money to the campaign but persuaded singer Isaac Hayes and comedian Bill Cosby to do the same.

“It wasn’t that he became any more outspoken and started to pop off. People just began to ask him questions,” Young said. “As long as he was playing, they were asking Hank about balls and strikes and pitchers and hitters. When he stopped playing, the questions changed, and he just responded to them. Hank has always been unappreciated and underestimated.”

Not by everyone. Former Braves owner Ted Turner asked Aaron to become manager of his team on two different occasions during the late 1970s, but Aaron declined both times. He did accept Turner’s offer to become a vice president and director of player development. During his 13-year tenure, Aaron oversaw a farm system that produced the likes of Dale Murphy and the foundation for a divisional title in 1982.

After leaving as director of player development, Aaron spent the rest of his years in baseball as a Braves senior vice president and assistant to the president. He also heightened his role as an entrepreneur, owning eight Arby’s franchises in Milwaukee during the early part of his post-playing career before he turned the bulk of his attention to his two car dealerships (BMW and Honda) in the Atlanta. He also had area after he ran his own restaurant in town.

“To be honest with you, I had all of this planned out, because I knew it was going to be hard for me after 23 years of playing baseball to just get into something else,” Aaron told the AJC in 2006. "I started out in real estate when I first started working for the Braves, and I ended up with the biggest crook in the world, losing about $1 million. I lost everything I had through my insurance and some other things. Whew! And back then $1 million was $1 million.

“But, having said that, I wasn’t going to let that keep me from doing well. I did have some money that I had saved through the years and some deferred money. And the reason I was such a great ballplayer and did some great things is because a lot of people said that I couldn’t do certain things.”

“When I got out of baseball, for instance, I read what somebody wrote in the paper after I got my first dealership, ‘Don’t put too much stock in this, because he’s going to fail.’ I remember that, and I said, ‘If I have to crawl at night, I won’t fail.’ I said, ‘I’m going to make all of these people eat their words.’ I’ll do anything not to fail, and that’s why I kept pushing.”

Along the way, there was a heart-wrenching divorce in 1971 from his first wife of 17 years, Barbara, and then there was his heart-warming marriage from 1973 through the present to his second wife, Billye, a former Atlanta television personality. There also were four children from his first marriage (Gaile, Hankie, Lary and Dorinda), his adoption of Billye’s daughter, Ceci, and grandchildren, and great grandchildren.

Something else motivated Aaron: needy people, particularly youngsters. He developed his “Chasing the Dream” foundation to help 755 underprivileged kids get an education.

“My wife [Billye] gives a lot, and I give a lot” he said. "But that’s what we’re here for. I just feel like nothing that we have belongs to us. It was given to me by God, and when we leave here, I don’t know of anybody who will go with a casket full of money.

“Why not let somebody else enjoy whatever I’ve been fortunate enough to accumulate?”

Thomas Stinson contributed to this article.