To Ebrahim Khosravi, south metro Atlanta looks a lot like the future of American tech — a young, diverse, mobile population that has never known a world without the Internet or cell phones that fit in your pocket.

But while much of the area north of Interstate 20 is gaining a reputation as a hub for financial, cyber and IT services, metro Atlanta’s southside — Clayton, Henry, Fayette and South Fulton counties — has largely been ignored by the tech world.

That’s been the case even as its leaders say they want to reach out to communities of color.

“We are in a unique position in tech,” said Khosravi, dean of Clayton State University’s College of Information and Mathematical Studies, which recently added cyber security to its graduate program. “About 62% of our students are minorities and we should be advertising that.

“We should tell people we have the workforce that is underrepresented in your area,” he said.

There’s a lot at stake.

Tech businesses added $650 million to Georgia’s economy in 2019, according to the most recent data available from the Georgia Technology Association. And employment in the industry accounted for 290,000 jobs, about 66% of which were in metro Atlanta.

In addition, the GTA said metro Atlanta ranks 6th in technology across metro regions nationally. But breaking through hasn’t been easy for south metro communities.

Josh Penny, director of corporate citizenship at digital marketing company Mailchimp, said the company has partnered with Clayton State in the last few years on training and educating south metro tech students.

While the company has gotten some industry colleagues to take a look at the region, south metro continues to be largely ignored because of the economic divide that has long separated north and south metro, he said.

“It’s partially about historically how the region has operated and developed,” said Penny, a graduate of Jonesboro High School. “We’ve seen chronic under-investment south of I-20.”

Investment shortcomings

Clayton Commission Chairman Jeff Turner said the county is trying to up its game by setting aside more funding for business development, including tech companies. Leaders have received a few bites from companies interested in locating in the county’s northern communities, but nothing concrete.

“The wave of the future is technology and if we can get ahead of the curve we can help the young people who have interest in that field,” he said.

South metro leaders have a lot of work to do to achieve that.

Metro Atlanta communities to the north benefit from having several colleges and universities — Georgia Tech, Clark Atlanta, Emory and Georgia State — close to one another to create a critical mass of employees for companies seeking talent.

The city’s northern end also is home to the city’s biggest brands, many of which have created incubators around Georgia Tech.

In addition, Atlanta and its northern suburbs have put more money into the infrastructure necessary to attract tech companies, such as fiber optic cabling under the city’s streets to boost the speed of communication. They also have launched incubator campuses such as Atlanta Tech Village to fund entrepreneurs in the sector.

“When you think about south of I-20, it does lag a great deal,” said Shannon James, president and CEO of Aerotropolis Atlanta, a business group helping to bring development to areas around Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport.

James has been in talks with Plug And Play Tech Center, a company that supports start ups and incubators, to create a hub around the airport. But the south metro needs an eco-system that makes it easy for companies with minimal effort, he said.

“When the Amazons, Googles and Mailchimps of the world come down and want to work with someone, they are looking for partners,” James said. “Where we are struggling from a capacity standpoint is to be able to have that infrastructure to support those partnerships.”

And because the tech industry is so well represented on Atlanta’s north side, some companies may think it’s easier for those south of I-20 to commute instead of trying to expand their reach, said Colin Martin, president of the Fayette County Chamber of Commerce.

“We would love to have startups here, not only for the economic impact, but for the culture it creates,” he said.

Josh Fenn, executive director of the Henry County Development Authority, said Southern Crescent Technical College had been trying to expand its reach into metro Atlanta’s second fastest growing county in hopes of being a catalyst for incubators and other educational opportunities. But they effort has been slowed by the pandemic.

”Before the pandemic, we were getting looks from ‘shared workspace’ firms as this part of the region was not the market of first choice by WeWork and others,” Fenn said. “We were getting some interest. We have some entrepreneurs who have filled that space but we need more ... and there is a market case for Henry.”

Signs of tech life

For Trina Reaves and Janetta Greenwood, that infrastructure starts in kindergarten through high school.

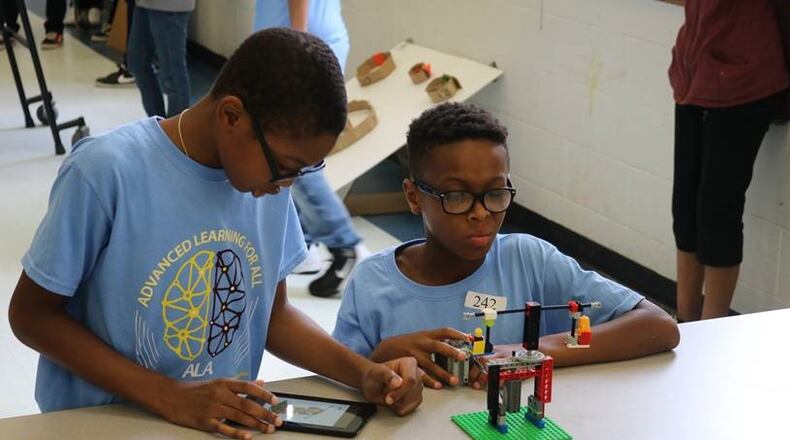

Reaves, director of STEM and Innovation for Clayton County Schools, and Greenwood, the district’s coordinator of science, said they try to offer students the breadth of tech experiences — from learning about gaming to visiting farms that use technology.

Developing local incubators and startups could add another layer to that strategy. Children would get to see the entrepreneurial side of tech and learn what it takes to develop an idea into a finished product.

“One of the things that we recognize is that the students just need access to opportunities,” Greenwood said.

Jason Bass, who has developed an app called Brewery Hours HQ and is owner of web company JasonHunter Design, said the infrastructure is slowly developing.

He is part of StartUp Fayette, an initiative of the Fayette Chamber of Commerce that brings together entrepreneurs, including those in tech, to talk strategy, funding and collaboration.

But a pitch contest planned for November shows how far south metro tech has to go. The winner will get web design help as a prize from his company and another local entrepreneur is offering headshots to the victor. Bass would love to see a “Shark Tank”-type result where the best idea gets funded.

“I’m having trouble getting entrepreneurs to come out of the woodwork,” he said. “They would come out if there was money.”

Frank Patterson, CEO and president of Trilith Studios, said there are more opportunities for the south metro area than one would think.

Trilith, formerly Pinewood Atlanta Studios and home to “Spider-Man: Homecoming,” “WandaVision” and the multi-billion dollar “Avengers” franchise, has brought a lot of Atlanta’s tech talent south. The studio also tapped into the fiber optic network in downtown Atlanta to make sure it can communicate with studios all over the world just as efficiently as if its offices were in Midtown Atlanta.

The challenge, he said, is bringing everyone together to get the infrastructure that is developing to work together as one.

“Atlanta has been a great resources for young talent, including what’s happening on the southside,” he said.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured