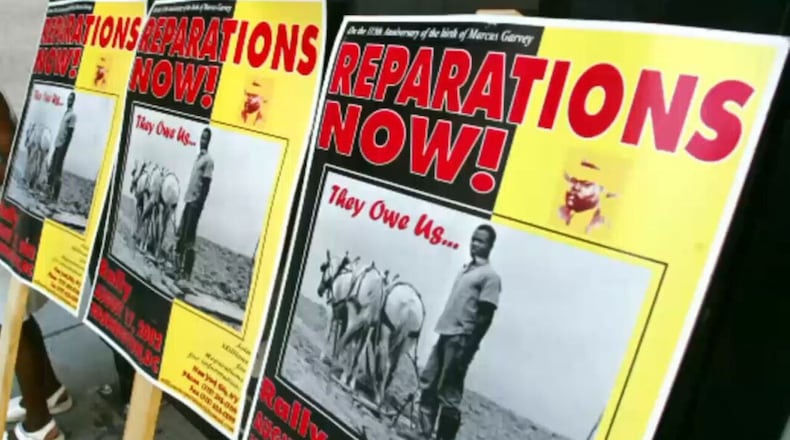

As calls for reparations for Black Americans continue to grow, the conversation will make its way to Atlanta.

The nonprofit Decolonizing Wealth Project will bring its “Alight Align Arise: Advancing the Movement for Repair” national conference to Atlanta this week. It convenes key stakeholders, coalition leaders, celebrities, business leaders and funders to discuss local and national reparations efforts.

High-profile speakers include Nikole Hannah-Jones, who won a Pulitzer Prize for helming the groundbreaking “1619 Project” in The New York Times in 2019, and Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose 2014 Atlantic article, “The Case for Reparations,” jumpstarted a new round of thinking around financial reparations.

The conference arrives as a Fulton County task force is in the midst of a years-long study into possible reparations for local residents — the first such county-led task force in the country.

“This conference is really a moment because folks for decades, or even longer, have been advocating for reparations for Black people in this country,” said Edgar Villanueva, the conference’s organizer and founder of Decolonizing Wealth Project. “But after the murder of George Floyd, the movement and the demand for reparations has just grown exponentially.”

In 2021, in the wake of Floyd’s killing by a Minneapolis police officer, Michelle Bachelet, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, issued a sweeping report that looked at centuries of mistreatment of Africans, most notably through the transatlantic slave trade, and called for a “transformative” approach to address its continued impact today.

She urged countries worldwide to do more to help end discrimination, violence and systemic racism against people of African descent and “make amends” to them — including through reparations.

Nationally, since the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, Democrats and activists have taken reparations up as a conversation. Republicans have been resistant, but several cities and states have set up commissions to study reparations to Black Americans.

In May, Congresswoman Cori Bush, a Democrat from Missouri, introduced a resolution arguing why the federal government must provide reparations to descendants of enslaved Black people and people of African descent. Her Reparations Now Resolution outlines the various forms those reparations should take and calls for $14 trillion worth of compensation for slavery and Jim Crow.

Democrats have floated bills and resolutions with similar language during every legislative session since 1989.

Nikema Williams, who represents Atlanta in Congress, supports the resolution and “wide-ranging” reparations.

“People who profited from the enslavement of 10 million people remain in positions of power, and in far too many instances, the families of enslaved people have received no reward,” said Williams, a Democrat. “America was intentional in disenfranchising Black communities continuing to do things like underfunding our schools, destroying our neighborhoods, and voter suppression.”

Credit: Anna Webber

Credit: Anna Webber

In his influential 2014 article arguing for reparations in the United States, Coates wrote: “Two hundred fifty years of slavery. Ninety years of Jim Crow. Sixty years of separate but equal. Thirty-five years of racist housing policy. Until we reckon with our compounding moral debts, America will never be whole.”

Whenever metro Atlanta resident Malika Redmond knocks on doors to talk to women about human rights, youth empowerment and civic engagement, the question always comes up: What do reparations look like?

“We engage with our constituencies about issues important to them,” said Redmond, a feminist researcher and human rights leader who cofounded the nonprofit Women Engaged in 2014. “The issues include how do we make comprehensive, longstanding shifts to change outcomes because of systematic racism. Reparations are part of that conversation.”

Since the end of slavery, and as far back as Reconstruction, Black Americans have been trying to catch up economically and be compensated. While cash is often the first consideration, experts and economists have argued that reparations can come in other forms, such as helping purchase homes and start businesses, or easier access to education.

Villanueva, the conference organizer, said what reparations look like depends on who you ask.

“Our approach is looking at past atrocities and harms that have been oppressed on Black people and asking those people what they want to need to heal and move forward,” Villanueva said. “There’s no amount of money that can ever undo or fix what has happened to Black people in this country.”

Locally, Fulton County is taking a serious look at the issue. In April 2021, the county formed the Fulton County Reparations Task Force to come up with possible compensation recommendations which could take the form of cash, tax credits or even scholarships.

It was the first county-led reparations task force in the former Confederacy. It follows the footsteps of places like California, which formed a task force in 2020 and issued a report two years later outlining how housing, incarceration, property seizure, devaluation of Black-owned businesses and unequal health care have harmed Black communities.

In 2021 the city of Evanston, Ill., became the first U.S. city to offer reparations to African American residents — in the form of housing grants.

Last January, Fulton commissioners approved $250,000 in funding for the task force to cover the cost of research for a series of studies that are expected to be published in 2024.

“The conversation is growing,” said Karcheik Sims-Alvarado, who chairs the Fulton task force. “We are having greater conversations about reparations than we were having 10 years ago.”

Alvarado said the task force will begin work on the study in July, followed by a series of town hall meetings.

Redmond, of the nonprofit Women Engaged, will keep knocking on doors.

“For us, reparations is part of a comprehensive response to decades and centuries of oppression that includes economics, advancement opportunities and a cultural shift,” Redmond said. “This is about an acknowledgment of wrongs.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured