Accreditation announcement coming for DeKalb

Timeline

December 2012: The Southern Association of Colleges and Schools places DeKalb schools on probation

February 2013: Cheryl Atkinson resigns as superintendent and is succeeded by Michael Thurmond

March 2013: Gov. Nathan Deal suspends six school board members and names replacements

November 2013: The Georgia Supreme Court upholds the removal of the six school board members

People in DeKalb County are anxiously awaiting an announcement Tuesday about the accreditation of their schools.

The political and financial turmoil that roiled Georgia’s third-largest school system in prior years are a thing of the past according to some hopeful observers, who believe the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools will finally erase the stain that has soiled DeKalb’s name for more than a year.

Mark Elgart, the president and chief executive officer of SACS parent company AdvancED, will meet with the county school board at 10 a.m. to reveal the findings of a review conducted last month, a year after his agency placed the district on probation. Gov. Nathan Deal also is expected to give a speech at the board meeting.

The drop in accreditation, and a SACS threat to strip accreditation altogether if school leaders failed to reform the system, plunged the district into crisis. The superintendent walked out, the governor intervened and the state supreme court got involved.

Now, officials and observers say the district of 99,000 students has stabilized and deserves to come off probation.

“I’m extremely optimistic,” said Ernest Brown, one of two parents SACS interviewed in 2012 during its investigation of the district. (Most of those interviewed by SACS were school officials.) The school district has dug out of its budget deficit, he said, and Deal’s intervention — he replaced two-thirds of the nine school board members — neutralized a major concern about school board meddling.

SACS accused the former school board members of infighting, influencing personnel decisions and otherwise throwing their weight around inappropriately.

“The reason we went on probation was not because of what was going on in the classroom but because of what was going on on the school board,” said Brown. “There’s a 180-degree difference.”

Elgart had no comment about his pending announcement. SACS wants the superintendent and school board to hear the results first, a spokeswoman said.

Superintendent Michael Thurmond, who immediately began addressing the accreditation concerns when he was hired in February, declined to speculate on Elgart’s plans but said he was hopeful for a “positive” outcome.

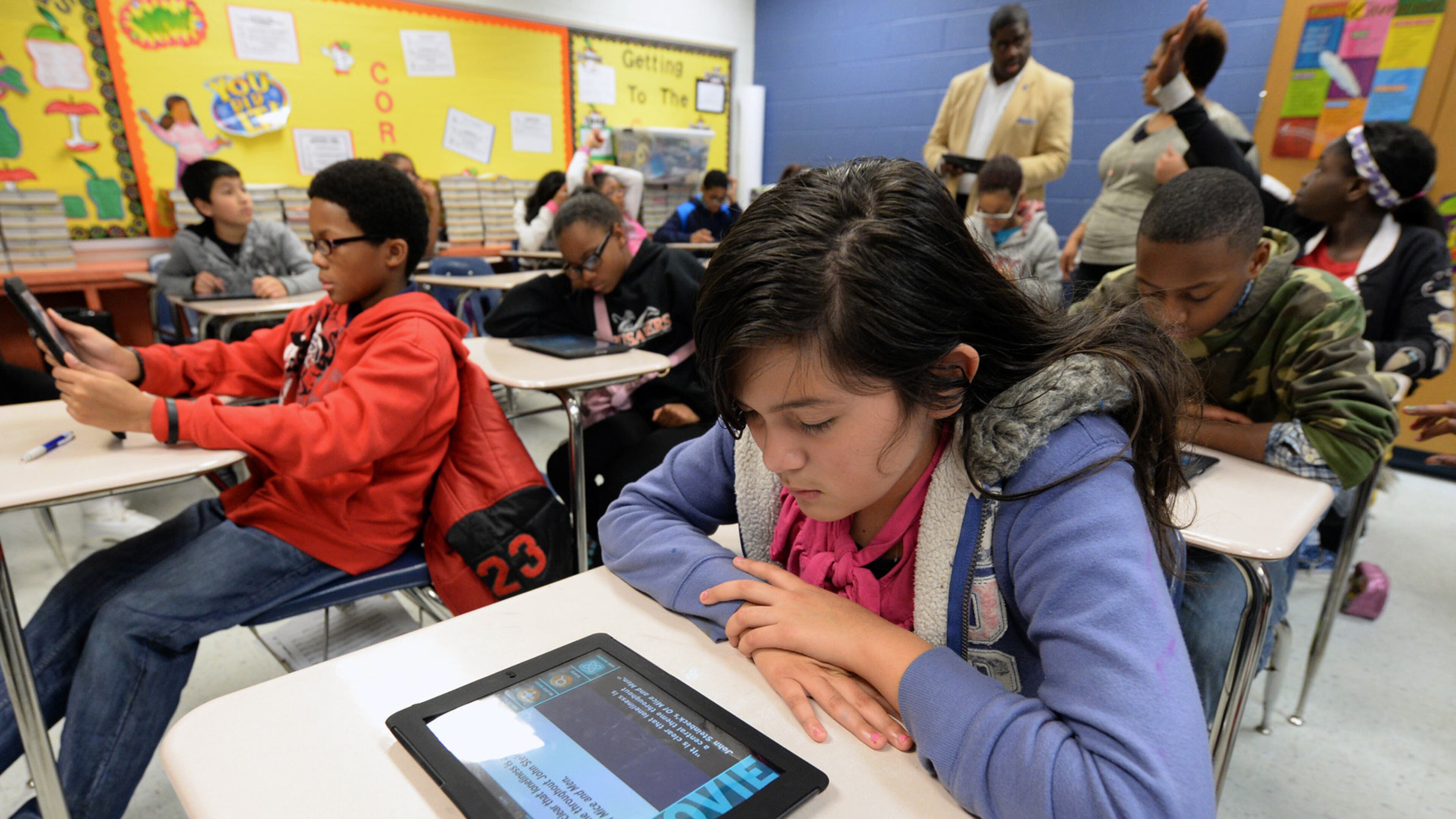

SACS gave DeKalb a list of 11 “required actions” to regain full accreditation. Topics included planning, instituting respect for the superintendent’s authority, fiscal discipline, effective deployment of technology and communication with parents.

“I feel like we made significant progress,” Thurmond said, adding that “not losing accreditation would be a very good outcome.”

Accreditation loss, an extremely rare sanction, would be traumatic. Many in DeKalb point to Clayton County, which in 2008 became the first school district in four decades to lose accreditation under SACS. Students fled and the tax base eroded as the value of real estate tumbled.

Probation alone has been enough to undermine economic growth in DeKalb, said Arnie Silverman, a board member of the DeKalb Chamber of Commerce.

“The fact that we have been on probation has been a negative for companies and businesses thinking of coming here,” said Silverman, a construction company executive. “It is important to the business community that we have a strong, clean school system.”

Luz Borrero, a county official involved with economic development, said the school system woes are a frequent concern among businesspeople and others queried in surveys and focus groups.

With the population of DeKalb aging, DeKalb hopes to attract more young families, but the probationary status has been an impediment. “The statistics show that we are not making ourselves more attractive to that population because of this,” said Borrero, who is DeKalb’s deputy chief operating officer for development.

Accreditation is important because colleges use it to judge the quality of schools their applicants attended. It can influence admissions and financial aid.

DeKalb has been on SACS’ watch list for a while. The agency had dropped the school district one notch below full accreditation — to “advisement” — in early 2011, and shocked many in December 2012 when it put the district on probation, skipping an interim step called “warning.”

A swift series of leadership changes followed. Cheryl Atkinson, the superintendent at the time, had been at odds with her school board and walked out midway through her contract last February. The board hired Thurmond just before Deal suspended and ultimately removed six board members. One sued all the way to the Georgia Supreme Court, which in November upheld the removals.

Thurmond, with the help of a more unified school board and a recovering economy, tackled the deficit. A lawyer, he cut back on payments to law firms and focused on ending a lawsuit that had drained away at least $18 million dollars since 2007. The suit involved the school district’s former construction manager, Heery International, Inc., which settled with a $7.5 million payment to DeKalb.

Elgart has said DeKalb was showing progress. During a visit last year, he said the district would likely keep its accreditation but remain on probation. Many, though, are hoping for a better outcome.

Borrero, the DeKalb government official, said the school district appears to have made deliberate progress in addressing SACS’ concerns.

“My expectation is that it will be very good news,” she said. “If not, I will be very disappointed.”