As powerful and significant as he was as a civil rights leader, C.T. Vivian was content with being the quiet one in the back while men like Martin Luther King Jr. and Andrew Young basked in the spotlight.

He waited until late in life to pen his autobiography. And even on the day he died, July 17, 2020, he shared the spotlight with his good friend, congressman and civil rights leader John Lewis, whose death was announced hours later.

That is why, a year later, his family is surprised at how Vivian’s legacy has grown, sparked by the posthumously published memoir, a rediscovery of his work and a planned museum that will showcase his vast book collection.

Credit: HANDOUT

Credit: HANDOUT

“Dad, in a way, has turned out bigger in death than he was in life,” said Vivian’s daughter, Denise Morse. “When he died, I thought after six months things would be over and people wouldn’t think about dad. I didn’t expect him to live on like he has.”

At the recent unveiling of the John Lewis statue at the new Rodney Cook Sr. Park, Morse pointed to a hill about 100 yards away.

That’s where the Georgia Peace Column will be built. Inside its pedestal, the C.T. and Octavia Vivian Library will house the couple’s 6,000 volumes of rare works by mostly Black authors.

Credit: National Monuments Foundation

Credit: National Monuments Foundation

The books are part of a vast collection of memorabilia that includes Vivian’s papers and sermons, along with his collection of rare artwork.

“Daddy left no money, no insurance and no equity in the house,” Morse said. “He left us what he loved – art, books and his written word.”

More than 250 boxes of the Vivians’ books have been cataloged and are in storage. The artwork, collected from all over the world, has been passed down to their six children. It is also in storage.

Vivian’s papers, speeches, sermons, essays, photos, letters, articles about the civil rights movement and notes, including those jotted on napkins and event programs, are at Emory University’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library. It also holds the works of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, as well as writer James Weldon Johnson and entertainer Josephine Baker, both civil rights activists.

Vivian initially donated his papers, along with his wife’s, to Emory in 2014. Clinton Fluker, the curator of the library’s African American collection said the family recently donated another 50 boxes of items.

“It really comprises their whole life, personally and professionally,” Fluker said. “My favorites are the letters that they wrote to each other over 50 years, where you see the relationship play out.”

Next month, at the Bronze Lens Film Festival, the library will premier a short documentary, “Small Steps,” about the work Vivian did to start Project Vision, which became the predecessor of the federally funded educational program Upward Bound.

“I love the fact that his works are to be maintained by a major organization like Emory because it helps keep him alive,” said son Al Vivian, adding that the family is just starting to plan a book of sermons culled from the papers.

Credit: custom

Credit: custom

In the park where the Vivian library will be located, Rodney Cook Jr. talked about plans to break ground on the Georgia Peace Column by next spring.

Cook’s father, the namesake of the park, was a white Atlanta alderman and state legislator who pushed for civil rights in the 1960s and cultivated friendships with the movement’s young Black leaders, including Vivian.

It didn’t make him popular among some white residents, so there were bomb threats and fear of kidnappings. In 1962, after a cross burning in their yard, a young Rodney Cook Jr., stopped talking and withdrew.

Vivian loaned the young Cook books, including a volume of poetry by Claude McKay, which featured Vivian’s favorite, “If We Must Die.”

“Having just suffered what I had suffered, the poem rang true,” Cook said. “C.T. was naturally quiet, and he saw that in me when I was a child. I was tortured by the civil rights movement, and he gave me a lifeline.”

Now, as the founder of the National Monuments Foundation, Cook is spearheading an effort to get at least 17 more statues of civil rights figures erected in the park, which sits in the shadow of both Mercedes-Benz Stadium and King’s former home.

Vivian announced in 2018 that he wanted his book collection to go in the Peace Column as the centerpiece of Cook Park.

“I wanted to do this in his lifetime, but things take time,” Cook said. “It is ironic that he gave me books as a child, then entrusted his whole library to me.”

Credit: ALYSSA.POINTER@AJC.COM

Credit: ALYSSA.POINTER@AJC.COM

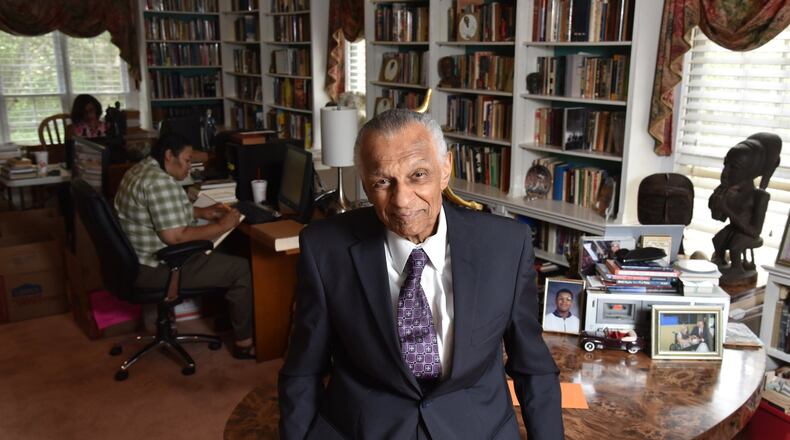

Cook said the library will be a re-creation of the one in Vivian’s Cascade home, down to his favorite reading spot.

Vivian’s book collection is one of the most extensive collections of Black literature in the city, carefully curated over 80 years and featuring first editions by the likes of Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes and W.E.B. Du Bois. Some are signed, like a copy of Phillis Wheatley’s 1773 “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral,” the first known book authored by an African American woman.

“We never thought the collection was valuable in a sense of money,” Vivian told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2018. “They were valuable in the sense that we can read our history. I want every Black child to be able to read about themselves. So books about Black people were always nearby for my children and for anyone who wanted to read about Black people and understand how we got this history.”

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Al Vivian remembers attending a housewarming party in the early 1990s. As an ice breaker, the host whipped out a Black history quiz game. Al Vivian dominated the game.

Later, his father reminded him of the family’s “Hall of Pride.” While living in Chicago in the late 1960s, the long hallway — leading to the library — was lined with framed pictures and biographies of famous African Americans.

“He reminded me that we were learning on a daily basis,” Al Vivian said. “We were always learning about Black history.”

Credit: ALYSSA.POINTER@AJC.COM

Credit: ALYSSA.POINTER@AJC.COM

Morse said that her parents would plan their trips across America to include stops at bookstores and frequently returned home with a trunkload of books. Octavia Vivian also was an author — she penned the Coretta Scott King biography.

Often, one of Vivian’s travel companions was David McCord, a book dealer known for finding the rarities that Vivian craved.

“I remember how much fun it was to bring books to C.T. and watch him go through all of them,” said McCord. “He was very sophisticated in his tastes.”

It was McCord who secured the Wheatley book and first edition of Jean Toomer’s “Cane,” without a dust jacket.

“C.T. used to say that they always knew we could write, they just never knew we could read,” McCord said.

Yet, Vivian waited before undertaking his own memoir.

While contemporaries like Lewis and Young published heralded autobiographies in the 1990s, Vivian, who had such an appreciation for the written word, waited until he was in his 90s.

“My takeaway is that he was always too busy and too humble,” said Steve Fiffer, who wrote the book with Vivian.

Published after his death, “It’s in the Action: Memories of a Nonviolent Warrior,” has brought a new appreciation for Vivian. His book from 1970, “Black Power and the American Myth,” was also reprinted and re-released this year as a 50th-anniversary edition.

“The response has been fantastic. All positive,” Fiffer said. “The most heartening thing to me is people who said, I didn’t know about this guy. One of the real pleasures is that there is more recognition coming to him now.”

Here is a snapshot of some of the books in the Vivian collection.

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral

Written in 1773 by Phillis Wheatley, “Poems,” is the oldest book in the collection. Born in Africa and brought by slave traders to Boston as a child, Wheatley quickly mastered English and learned to read and write. When few believed that Africans had the capacity to write poetry, Wheatley was put in front of a panel of 18 prominent Bostonians to prove it. Satisfied, the men wrote a preface to the book. Vivian owns a signed edition.

The Black Man: His Antecedents, His Genius and His Achievements

Published in 1863 by William Wells Brown, the book traces the lives of Nat Turner, Crispus Attucks, Denmark Vesey, Henry Highland Garnett and other men who had, through “genius, capacity, and intellectual development, surmounted the many obstacles which slavery and prejudice have thrown in their way,” and “raised themselves to positions of honor and influence.”

Journal of Negro History

Credit: Courtesy National Park Service

Credit: Courtesy National Park Service

A quarterly academic journal founded in 1916 by historian Carter G. Woodson. It covered African American life and history and was published until 2001. Vivian had the whole collection.

Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, an African

Credit: Submitted

Credit: Submitted

Sancho was a British composer, actor and writer. A former slave, he was seen as an “extraordinary Negro,” and a symbol of the humanity of Africans and the immorality of the slave trade. In 1782, two years after his death, his 160 letters were published, one of the earliest accounts of African slavery written in English. Vivian had a 1784 edition.

The Penitential Tyrant; or, Slave Trader Reformed: a Pathetic Poem, in Four Cantos — Written in 1807 by abolitionist Thomas Branagan, the book is his stern opposition to slavery.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured