What Remains: The power of Black family reunions

Book I: A legacy of presence

There was a moment last month when Reginald Thornton, surrounded by family in a small ballroom at a Cobb County Embassy Suites, paused — caught by a memory too large for words.

He swept his gaze across the room and watched adult grandchildren mingle, uncles in seersucker suits trade jokes and aunties in wide-brimmed hats share hugs, a heavy tapestry of lineage.

They represent three branches of the Thornton family — descendants of brothers Frank, Willie and Clarence.

But Reginald’s mind turned to his father, Hubbard “Herb” Thornton, who had died just a year earlier.

A man of quiet devotion, Hubbard’s absence now gave the gathering a sharper sense of purpose.

“We have to encourage the younger people to start attending,” said Walter Thornton, who moments before had invited everyone to rise to pay tribute to his brother, Hubbard, while also noting the need for a younger generation to pick up the baton to carry the family traditions. Only three members of the entire gathering — Walter’s grandchildren — were under 30. “We are not going to be here forever.”

That lodged in Reginald’s heart.

Last summer, he had missed the family reunion in Washington, D.C. He stayed behind to care for his ailing father, Hubbard, who had moved back to Albany to help his brother Frank run the family barbershop, the city’s oldest Black-owned business.

Reginald said his father, as he got older, understood the value of the reunions and keeping the family close.

“He always asked, ‘You going to the reunion? You talk to your sisters?’” Reginald recalled. “He was always checking in, organizing, pushing us to stay connected.”

Now, with grief still fresh and relief just beginning to settle, the reunion felt charged — not just with memory, but with meaning.

“Does the reunion mean more to me now, since his passing? Yes and no,” confessed Reginald, who planned this year’s reunion with his cousin Hank Young. “It doesn’t necessarily mean more, but it feels more important to be there.”

Across the room, Bob Thornton, now the family patriarch at 88, stood and nodded — as if absorbing the weight of every generation.

“We tend to end up letting others write our history when we can do it ourselves,” he said, his words measured, full of meaning. “The family is getting larger and the youngsters are getting smarter. We are pressing on to them that they write their history by living it well.”

The reunion wasn’t just a tradition, Reginald said later. It was reclamation.

Book II: The cultural roots of reunion

In the long shadow of slavery, family was the first casualty.

In a calculated and cruel dismantling of kinship, husbands were sold away from their wives, children were wrenched from their mothers’ arms and siblings disappeared — scattered across cotton fields and auction blocks, never to be seen again.

Between 1790 and 1860, historians estimate that more than 1 million enslaved African Americans were forcibly relocated from the Upper South to the Deep South in what was known as the “Second Middle Passage.” Peaking between 1820 and 1860, roughly a quarter of those sold were between the ages of 8 and 15.

“No relationship was protected,” said Villanova University historian Judith Giesberg.

After emancipation, as the Civil War ended and the 13th Amendment was ratified, many newly freed people set out to find those they had lost.

They walked roads, crossed state lines, wrote letters and contacted pastors.

Giesberg, through her project and now book, “Last Seen: The Enduring Search by Formerly Enslaved People to Find Their Lost Families,” has documented more than 5,000 desperate newspaper pleas from formerly enslaved people searching for family members — sometimes decades after separation.

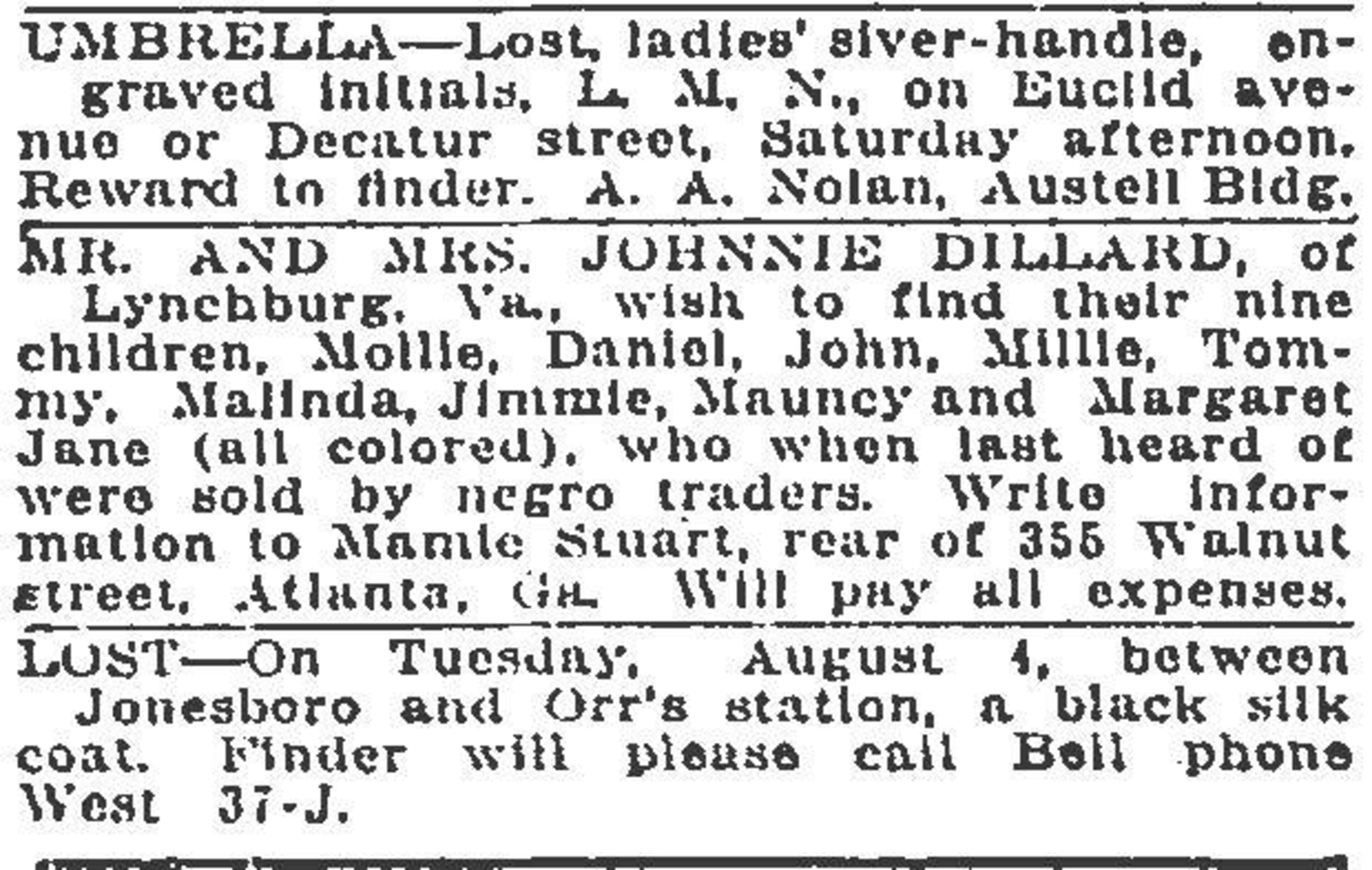

On Aug. 19, 1917, in what is now the “Atlanta Journal-Constitution,” a family posted a plea that reflected more than 50 years of heartbreak:

“MR. AND MRS. JOHNNIE DILLARD, of Lynchburg, Va., wish to find their nine children, Mollie, Daniel, John, Millie, Tommy, Malinda, Jimmie, Mauncy and Margaret Jane (all colored), who when last heard of were sold by negro traders. Write information to Mamie Stuart, rear of 355 Walnut Street, Atlanta, Ga. Will pay all expenses.”

Their cry for their stolen children appeared between a notice about a misplaced umbrella and another about a missing silk jacket — a haunting reminder of how Black lives were once valued less than others’ lost belongings.

Of the thousands of such ads, only about 2% resulted in reunion. But the pursuit of reconnection became a cherished feature of Black American life and birthed one its most sacred cultural rituals: the family reunion.

Multiple studies — including research from Pew, the National Council of Negro Women and the National Museum of African American History and Culture — suggest that African Americans are more likely than other groups in the U.S. to hold large, regular family gatherings and to feel a strong connection to their cultural roots.

One estimate, published by Julie E. Miller-Cribbs through the University of Michigan, found that nearly half of all travel by African Americans — and 70% of non-business travel — is related to family reunions.

White families often gather more casually around weddings or holidays. Latino families often maintain deep traditions of multigenerational celebrations rooted in “familismo.” Asian and Native American families may preserve kinship through tribal rituals, religious festivals and clan associations.

But few gatherings carry the historical and emotional weight of the Black family reunion, born directly from the need to repair what slavery tore apart.

That, Giesberg says, is no coincidence.

“What we see today has roots not just in the legacy of separation, but in more recent history, specifically the generation that grew up watching ”‘Roots,’” she said.

During the Great Migration, as millions of Black families left the South in search of safety and opportunity, reunions became a way to stay connected.

Then came the 1976 publication of “Roots” by Alex Haley. A year later, the television adaptation became one of the most-watched miniseries in American history.

Haley’s search for his original African ancestor in the U.S., Kunta Kinte, was transformative, sparking a genealogical awakening that inspired millions of African Americans to trace their roots and reclaim an often-erased history.

Book III: A name, a lineage and a homecoming

For journalist Sheeka Sanahori, it began, like many great stories do, with a hint of curiosity and a name.

In 2023, she nervously traveled to Jackson, Mississippi — a place she’d never been — to meet a branch of her family she had only recently discovered through Ancestry.com.

Her father didn’t want to go. Her husband had to work.

“My family thought I was nuts,” she laughed. “My dad was like, ‘I don’t know these folks. Why would I go?’”

But Sanahori went anyway. She packed up her 6-year-old son and drove to the Magnolia State from Decatur in the dead heat of summer, through miles of cotton fields, bracing for the possibility that she would not be welcomed at a gathering of more than 100 strangers — and feel like one herself.

“If I’m being very honest, I was also really nervous to go to a family reunion in which I didn’t know anybody,” she said. “I’d never met anybody who was there. I just knew that I was distantly related to this really large family.”

Once informal gatherings, Black family reunions have evolved into intentional rituals of remembrance, often supported by city and county offices across the South.

Usually held when school is out and travel is easier, they transform parks, churches and community centers into hallowed meeting grounds for families spread across states and generations.

Through oral histories, family Bibles, funeral programs and public archives, the gatherings have become opportunities to document and celebrate heritage with care and pride.

They are acts of representation — complete with matching T-shirts, commemorative booklets, generational portraits, storytelling circles, genealogy workshops, scholarship awards and health screenings.

That is what Sanahori walked into.

Dozens — over a hundred, in fact — milled through the banquet hall, sharing plates of food and photos and stories that stretched across generations. Sanahori wandered in carrying only her bloodline and a hope that she wouldn’t feel like an outsider.

“They welcomed me with open arms. They were so kind and they wanted to know everything about me to connect all of the dots,” she said. “It was surprisingly beautiful.”

That “welcome home,” as she calls it now, marked the end of a genealogical journey she began while pregnant, driven by the idea that her son deserved a history.

Her search led her to Angela Weathers, a distant cousin who was also trying to piece together the family’s tree.

Together, the two women unearthed records and oral histories pointing to Abraham Weathers, Sanahori’s great-great-grandfather and the keystone of their shared ancestry.

Angela had invited Sanahori to the family reunion many times before, but each year, life, doubt, distance — and her own family — held her back. Until that summer.

By the end of the weekend, Sanahori had not only met a new branch of her family. She also joined the reunion planning committee the following year, when the event was held in Atlanta.

“There were several generations of this side of my family that had basically separated during the Great Migration and just lost touch,” she said. “In a symbolic way, we were able to reunite those branches.”

She is still gently encouraging other relatives, like her father — whose middle name is Weathers — to join these reunions.

“I’ve been slowly chipping away at them,” she said of her relatives, laughing softly. “Trying to entice them to come to a reunion on this side. But I haven’t convinced them yet.”

Book IV: Walking history

By late June, as summer settled in, the Georgia air had already turned thick.

On a Tuesday afternoon, Thomas Dorsey, his daughter Tamara and cousin Paul Ponder made their slow, reverent way through the manicured grounds of the Fayetteville City Cemetery.

They walked 200 yards past rows of pristine headstones to a dividing road — more than a pathway, it was a symbol.

On the other side was the cemetery’s Black section, consecrated ground established over a century ago by their ancestors to ensure that formerly enslaved people would have a dignified place to rest.

Among the hundreds buried there, more than 100 are members of the extended Dorsey-Ponder family.

“I cry when I come out here,” Ponder, 75, said quietly, his eyes scanning the markers. He stood between the graves of his grandmother and father. “These are all of my people. Right here.”

For the Dorsey-Ponders, as for many Black families, history isn’t just remembered. It’s is walked, touched and wept over.

From the 1940s through the 1970s, annual reunions were a staple for the family. Then, for reasons that remain unclear, the tradition died.

In 2008, Thomas Dorsey revived the tradition driven by a sense of urgency.

“I don’t know exactly why they stopped,” he said. “But I wanted my people — the Dorseys — to know who they are.”

Thomas, 61, can trace his family back to one of Fayetteville’s most storied landmarks: the Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House, now a museum.

His third-great-grandmother, Silvey Holliday, was once enslaved by Dr. John Stiles Holliday, the home’s original owner and the uncle of the infamous gunslinger John Henry “Doc” Holliday.

Silvey later married Thomas Dorsey — Thomas’s namesake and third-great-grandfather — who had been enslaved by the home’s next owner, Solomon Dorsey.

After emancipation, Thomas and Silvey began building and investing in their community.

In 1884, Thomas and his son Isaac cofounded the Union Benevolent Aid Society at Edgefield Baptist Church.

Modeled after mutual aid organizations like Atlanta Life and North Carolina Mutual, the society offered support in life and dignity in death during an era of exclusion.

At its peak, the organization counted more than 500 lodges across Georgia. The Dorseys also purchased land for several Black cemeteries at a time when Black bodies were denied even burial rights.

“If you got sick, they’d help,” Thomas Dorsey said. “If you died, they’d bury you.”

Today, many family reunions include designated historians, relatives who trace family trees, gather records and present findings.

“It really helps, especially the younger people, figure out how they fit in,” said Clevlyn Anderson, corresponding secretary for the Atlanta chapter of the Afro‑American Historical and Genealogical Society. “It gives us our history. Seeing those connections can be powerful.”

Thomas Dorsey has long played that role in his family and has helped contextualize the Dorsey-Ponders’ legacy for the next generation.

As a boy, he often rode through Fayetteville with his grandfather, stopping at churches, homes and cemeteries tied to their story.

Those trips, “made me who I am,” Thomas said.

Now, he’s passing that inheritance on.

“My father took us to cemeteries and landmarks on the Southside and in Fayetteville,” said Tamara Dorsey, 29, a Clayton County teacher who’s helping plan this year’s reunion, expected to draw more than 150 relatives in October. “Always showing us who we are and where we come from.”

Earlier this year, the Georgia Historical Society installed a marker at the entrance to Fayetteville Cemetery, ironically positioned near the entrance to what was once the whites-only section, to honor the family and the Union Benevolent Aid Society.

During their recent walk, Thomas, Tamara and Paul moved among the headstones, naming relatives and noting dates.

They paused at the graves of Silvey and Thomas Dorsey. Isaac, their son, lies just behind them. A whole generation rests nearby.

Each headstone — some elaborately carved, others bearing names etched by hand — tells a larger story.

“Historically, we were taught we didn’t have much worth,” Thomas said, ducking beneath a tree for shade. “But our people were doing great things — even with less than we have today. Once you start looking at what they did, it changes everything.”

Book V: A Peachy reunion

For more than half a century, the Cloud-Travis family has gathered somewhere in America — every summer, without fail. They arrive from Ohio and Virginia, North Carolina and Washington, D.C., to remember, reclaim and to hold each other close.

What began in 1970 as a modest reunion has grown into a powerful tradition, rooted in the vision of two Black women born in 1920 and shaped, in part, by the family’s white ancestry and its unexpected link to one of America’s most pivotal economic events.

“They were strong Black women who loved their family dearly,” said Ken Oglesby, the family historian and reunion organizer, describing cousins Gladys Rogers Hilton and Willie Mae Satterfield — the women who started it all. “They were more than cousins. They were the mothers of this reunion.”

Their vision was simple but profound: to stitch back together what history had scattered.

During the Great Migration, as many Black families sought safety and opportunity in distant cities, the Cloud-Travis clan — like so many others — was dispersed. The reunion became a way to hold on to the branches of a family tree being pulled apart.

“They were trying to make sure that the younger people stayed together as a family,” said Sarah Pringle-Lewis, 71, whose mother was a cousin of Hilton’s. “They weren’t just remembering their own childhoods. They were trying to remove the miles.”

The miles have never stopped stretching. But the family has kept pace. Even a pandemic couldn’t break the chain.

“Every year, we ask if we should switch to every other year. And every year, we say no,” Oglesby said. “Because if we skip a year, it might be the end.”

As chair of the family’s history committee, Oglesby maintains the archive.

Earlier this month, he sat in his Alpharetta home with a mound of photo albums, flipping through sepia-toned portraits and pointing out relatives with pride.

He pulls out a large plastic folder containing nearly 50 years of newsletters mailed to relatives across the country.

This summer — 55 years after Gladys and Willie Mae’s first gathering — about 100 family members will meet for what they call “Another Peachy Reunion,” in Atlanta.

“For African Americans, family is everything,” Oglesby said. “For so long, we were stripped of our ties. This is how we reclaim them. This is how we remember who we are.”

Still, the family’s origins stretch even deeper into the American story.

From his pile of albums and documents, Oglesby pulls out a copy of “California Gold Book.”

It tells the story of how in 1848, Oglesby’s great-great-great-aunt — a white woman named Elizabeth Jane Cloud, later known as Jennie Wimmer — played an unlikely role in a turning point of U.S. history: she confirmed the authenticity of the first gold nugget found at Sutter’s Mill in California, helping to ignite the Gold Rush.

“She’s kind of a hidden figure,” Oglesby said.

Jennie Wimmer’s place in the Cloud-Travis family narrative reflects part of the strange, knotted history of African American families shaped by both Black resilience and white violation. The contradiction is not lost on the Cloud-Travis family.

That resilience and sense of purpose, leaves Pringle-Lewis — who is making the trip to Atlanta from Maine — both astonished and proud.

“I’m just always impressed that — and this is true for most African American families, if not all — that we survived,” she said. “That we know who we are. And that we want to be together. Who would’ve thought that a hundred years ago?”

Book VI: What remains

Back in that Embassy Suites ballroom, as the legacy of Hubbard Thornton hung gently in the air, the family prepared to close the circle.

Around the room, T-shirts and a family crest displayed images of identity: a barber pole, a tractor, a barn, visual tributes to the Thornton family’s work, land and legacy. They trace their roots to Albany and the red clay of Southwest Georgia — land hard-earned and held through generations of love and perseverance.

In the 1940s, Clarence Thornton quietly defied conventional odds by purchasing more than 150 acres of farmland, at a time when Black landownership was both rare and hard-won.

Today, that land remains in the family’s care, tended by his granddaughter, 81-year-old Jacqueline Harper.

For the reunion, which was attended by about 50 family members, Harper stitched a quilt titled “Love” — a tangible thread in a lineage shaped by separation and survival.

At the close of the luncheon, Harper rose and carefully folded the “Love” quilt into the hands of Nikki Moon, Hubbard’s daughter and Reginald’s sister.

“My father was supposed to get this last year,” Nikki said, her voice catching.

Her tears weren’t just for what was lost — they were for what remains.

More Stories

The Latest