Cobb County voters reject three cityhood movements

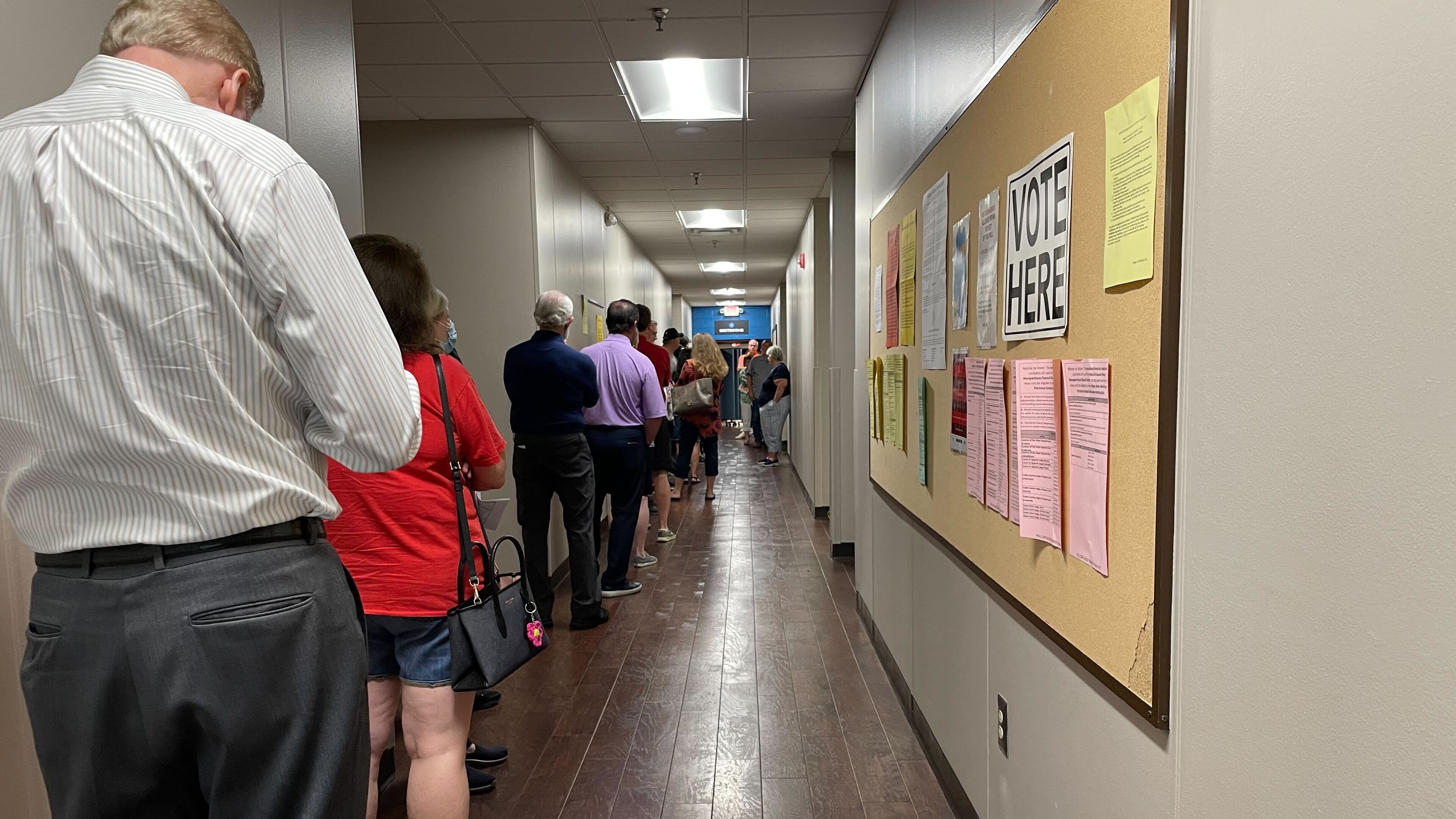

Voters across unincorporated Cobb County rejected efforts to form three new city governments, in a rebuke to Republican state lawmakers who rushed the proposed cities to the ballot.

Aside from one exception in the 1960s — a city of just 200 people that later dissolved — it has been over a century since Cobb County residents have formed a new municipality. And on Tuesday, when asked by cityhood supporters to create new governments to preserve their suburban way of life, voters opted instead to preserve something else: Their unincorporated slice of Cobb County.

Had the three cities been approved, they would have eliminated much of the remaining unincorporated land in Cobb. Instead, voters overwhelmingly voted for the status quo, following an abbreviated campaign in which residents and county officials alike complained that they were given too little time to understand the full implications of a decision that would have wide-ranging consequences for Cobb’s future.

In unofficial results Wednesday morning, 73% of East Cobb voters were opposed, the Lost Mountain cityhood effort trailed 58% to 42% and Vinings was rejected 55% to 45% with 100% of precincts reporting.

A fourth proposed city, Mableton in South Cobb, will appear on the November ballot.

The three cityhood movements, all led by Republicans, were widely viewed as a backlash to Democratic control in the county’s most conservative areas. This year’s was the first election since Democrats took over the Cobb Board of Commissioners in 2020, ending decades of GOP dominance in the northwest Atlanta suburbs.

Cityhood supporters promised that each of the three would be limited in scope, offering only a handful of services, such as planning and zoning, code enforcement and parks and recreation. Only East Cobb planned to provide its own police and fire departments.

All three are wealthier, whiter and more conservative than the county as a whole. Proponents said a city government was needed to block unwanted development from their affluent rural and suburban neighborhoods.

Misinformation was widespread throughout the abbreviated campaign, after supporters moved the election date up from November to May. In town halls, mailers and interviews, cityhood supporters claimed without evidence that Democratic Chairwoman Lisa Cupid was targeting the county’s low density neighborhoods for unwanted development, such as apartments and laundromats.

But that message fell flat with voters. Critics said the cities were rushed to the ballot, leaving voters with too many unanswered questions to make an informed decision.

Opponents also questioned whether a new layer of government was needed to accomplish the stated goals of cityhood supporters. County planning documents, which govern future zoning decisions, envision the three areas remaining predominantly low density.

Lost Mountain in West Cobb would have immediately become Cobb’s largest city, with a population of 75,000. East Cobb’s proposed city limits cover nearly 60,000 residents, while Vinings would have had a population of about 7,000.

District 3 Commissioner JoAnn Birrell, R-Northeast Cobb, easily withstood a primary challenge and will face Democrat Christine Triebsch in the November general election. Birrell defeated Republican challenger Judy Sarden, receiving 77% of the vote in unofficial results.