OPINION: What raising the age of juvenile offenders has to do with more jails

Brace yourselves. There’s talk about building more prisons for juvenile offenders, and you know what that means. More poor black and brown kids could be heading to the slammer soon.

If you missed that bit of news earlier this month, here it is again.

Juvenile Justice Commissioner Tyrone Oliver told a House panel studying legislation to raise the age of juvenile court jurisdiction to include 17-year-olds that Georgia would need at least four new secure juvenile centers — 50 beds at each — to house the 17-year-olds in just three Georgia counties.

According to people who should know, that simply isn’t true.

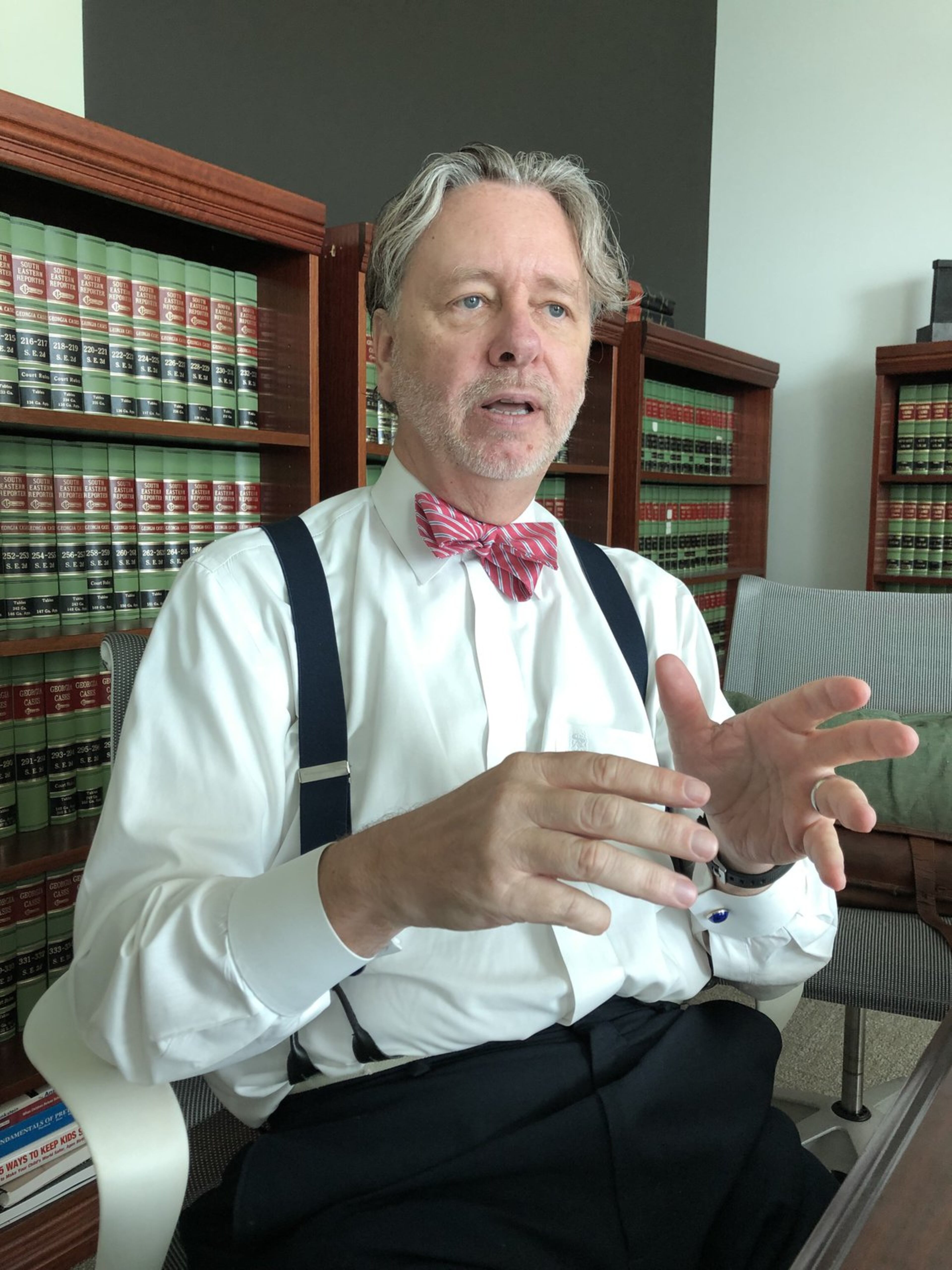

“Georgia has seven secure facilities that you can send kids away on felonies,” said Chief Judge Steven Teske of the Clayton County Juvenile Court. “They have a capacity for 746 youths, though they are authorized for as many as 847 youths. Currently, there are only 366 youths housed in those centers, and the Department of Juvenile Justice is set to close the Sumter center because of declining populations.”

On top of this, Teske said, there has been a steady decline in both youth arrests and long-term incarceration in the state’s youth detention centers since 2009.

In fact, he said, court referrals have fallen nearly 60%.

Oliver would not comment for this column.

RELATED | Raising age for charging as adults could require new Ga. facilities

Here’s the other thing Teske believes we should keep in mind as you consider this: The vast majority of Georgia 17-year-olds are arrested on drug charges, larceny, simple assault, and disorderly conduct, not violent offenses, which comprise only about 5% of arrests.

So why in the world are we subjecting all these high school students to the harshness of the adult system all because we’re scared of 5%? This is a “prophylactic response” — Teske’s words, not mine — to a problem that in the end hurts a lot more kids because we’ve now exposed them to violent adult criminals.

How big is that 5%? Oh, about 335 youths. In the entire state. Even if you increased that to 10% of the kids, it’s still less than 700 across the entire state.

So, what gives?

Teske suspects that the state’s auditor who provided Oliver the numbers didn’t consider that it is juvenile court judges who decide whether a juvenile is supervised in the community or is sentenced to a facility.

When adults get arrested, they go to jail, he said. When kids get arrested, they go to juvenile court intake for screening, and the intake officer decides who is detained. Far fewer of these 17-year-olds would be eligible for jail in the juvenile system because most are nonviolent.

Under House Bill 440, sponsored by Mandi Ballinger, chairwoman of the House Juvenile Justice Committee, the state would allow cases involving 17-year-olds to be handled in the juvenile court system, keeping those under 18 out of state prisons and giving them access to services that would hopefully prevent them from becoming hardened criminals.

So you can see why this news really ticked Teske off.

“How do you get $200 million to build new facilities when you have all these excess beds that are not being used?” he asked. “And how do you get folks like these auditors to pick up the phone and call the 11 other states that have been through this, with very positive outcomes?”

Good questions.

RELATED | New chief vows cultural change in juvenile justice agency

Marcy Mistrett, CEO of the Campaign for Youth Justice, a national initiative to end the practice of prosecuting, sentencing and incarcerating youths in the adult criminal justice system, has seen this kind of reaction to proposed raise the age legislation before.

“When Connecticut passed the first raise the age law over a decade ago, they were riddled with fear,” Mistrett said. “Fear the juvenile population would double, fear they would need more facilities, fear that it would cost more than $100 million. But none of this happened.”

Instead, youths entering the juvenile system dropped 63%, she said, they closed two facilities, costs went down and $39 million has been reinvested in communities. More importantly, other states that embraced this law experienced these same results.

When the initiative began in 2007, Mistrett said, there were 14 states in which the age of adult criminal responsibility was under 18. That meant no notice to parents when they got arrested, no parent had to be present when they were questioned by police and a permanent stain on their record. Now there are only three — Texas, Wisconsin and Georgia.

Georgia spends $390 million on juvenile justice each year. If you add every 17-year-old arrested last year, DJJ will still serve fewer kids than it did in 2013, but its budget keeps growing, Mistrett said.

“So it’s absurd to say this is a $200 million-plus initiative. If 47 states across the country have figured out how to do this, I have every bit of confidence that Georgia can, too.”

Although there will be some startup costs to train stakeholders about the new law and to let the public know about the changes, Mistrett said they would be minimal.

“We recommend that Georgia appoint a task force to ensure smooth implementation,” she said. “We’ve given the state multiple financial models from other states to choose from, and all they have to do is pick one.”

Mistrett said that she has reached out to Commissioner Oliver to offer assistance and connect him to other DJJ leaders and that from all she has heard he is the leader capable of implementing this law.

Given recent developments, Teske fears “raise the age” won’t get passed because Georgia will allow questionable costs to decide what to do instead.

“I would just like to ask the public how would you feel if it were your 17-year-old kid who was still in high school, did a stupid teenage thing and was locked up with all these adults in the county jail waiting to be processed,” he said. “I call it my child test.”

Teske said it’s hard for him to swallow the continued harsh treatment of 17-year-olds, knowing how much capacity there is to save them.

There may be a lot of folk out there like Teske, but he’s the only one I know willing to consider the “white elephant” in the room — most of the kids we’re talking about are poor African Americans and Latinos.

“A lot of people with my complexion have difficulty making the connection between the ‘Get Tough’ policies on 17-year-olds and how they target mostly poor black and brown kids,” Teske said. “We can’t fix poverty in Georgia if we do things to poor children that make them poorer, and leave them with no hope for escape.”

If your moral compass won’t allow you to see the white elephant, just apply Teske’s child test and ask yourself what would you do if it were your 17-year-old facing jail time?

Find Gracie on Facebook (www.facebook.com/graciestaplesajc/) and Twitter (@GStaples_AJC) or email her at gstaples@ajc.com.