This Life with Gracie: Morehouse president wants tuition to play smaller role in who can go

Two nights in a dorm room is by no means a long stay, but Morehouse President David A. Thomas is hoping it is enough to begin to understand his newest customers — freshmen — and what they need, expect from their experience.

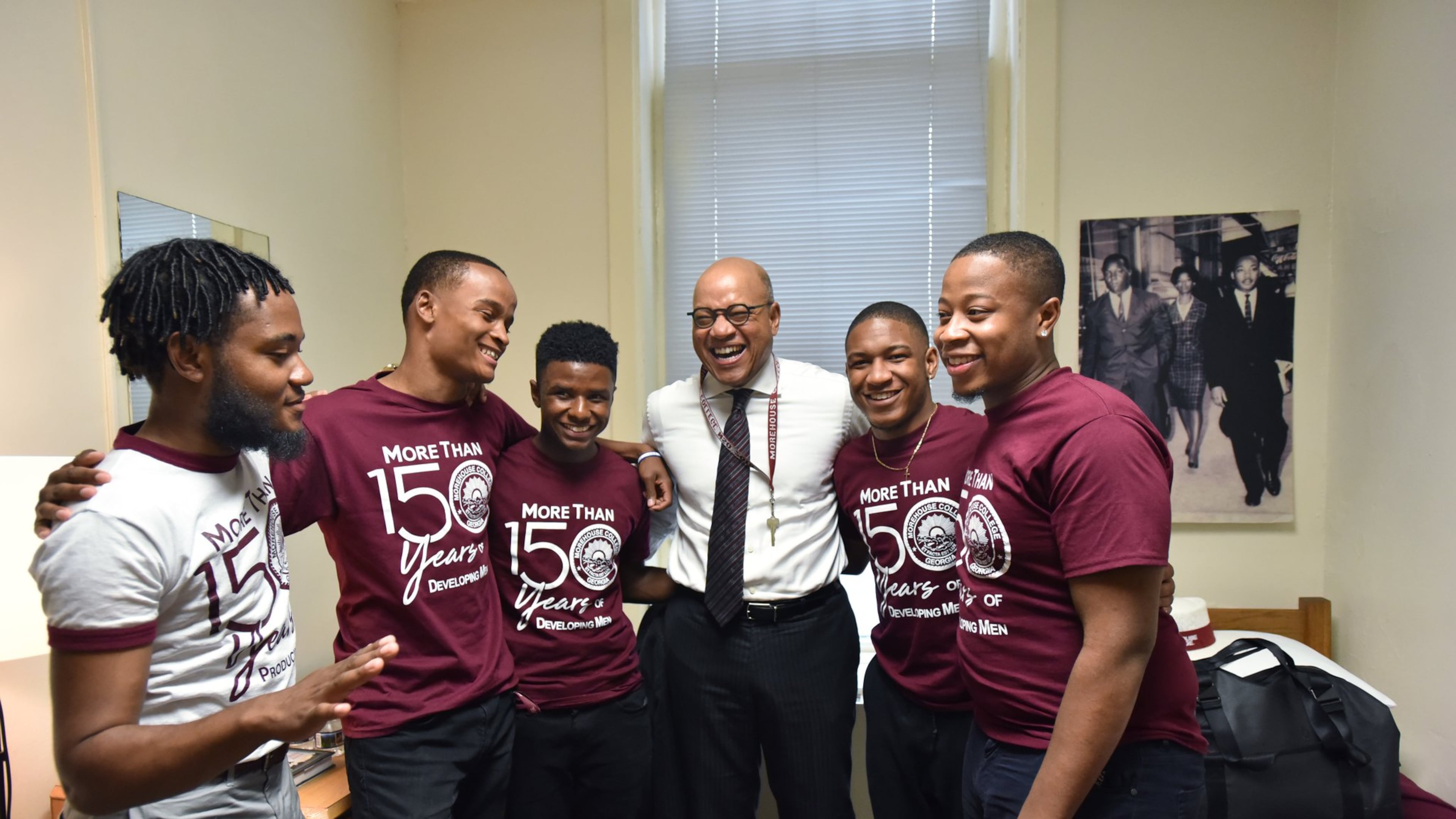

And so there he was last week in Room 116 of Graves Hall, a five-story brick building that once housed all that was and is Morehouse College, getting a glimpse of a day in the life of a Morehouse freshman, surrounded, of course, by Morehouse men.

He’d barely crossed the threshold and dropped his black duffel bag on the twin bed when Marcus Washington, residential adviser, launched into his spiel, a laundry list of do’s and don’t. Do fill out the three forms left on his desk. Do make note of the condition of the room. And do sign the key agreement. And don’t even think about having a visitor before the college’s October homecoming.

Thomas, who assumed office as president in January, won’t be here until homecoming but nods in agreement as a half-dozen reporters and photographers laugh.

For him, this move is both serious and symbolic. It is also very personal. You might have read some of that story in this newspaper earlier this year.

From the time he was a little kid, Thomas wanted just two things: to become president of the United States and to go to Morehouse.

RELATED | Morehouse valedictorian headed to Harvard Law School

He was a poor kid from a working-class family in Kansas City, Mo. No one in his family had ever gone to college, but he’d read somewhere that slain civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was a Morehouse grad.

He knew, too, that he did not want to be a janitor like his father. He’d done that. Swept floors. Cleaned toilets.

“You hate this?” his father would say to him, studying his face as he pushed a mop. “If you go to college, you won’t have to.”

Thomas began to take note of other men in the community, at his church who’d gone to Morehouse, his dream school.

He was a standout at his high school, a star student with a bright future. When it came time to apply for college, Morehouse was his first choice. Yale was second but only because his counselor insisted he had a backup plan. He and his parents hadn’t even heard of the school before then.

It was a good thing he had a backup plan. Yale offered young Thomas a full ride. Morehouse did not offer him a scholarship.

He was disappointed, but when he graduated from Paseo High School in 1974, family finances dictated his college choice. Yale it was.

Even after he’d moved on, Thomas never forgot the dream, keeping up with Morehouse in newspapers, magazines, word-of-mouth.

Four years later, he graduated, earning a bachelor’s degree in administrative sciences, and then three master’s degrees: one at Columbia University and two at Yale.

He’d eventually earn a Ph.D., too, at his alma mater and then work as an assistant professor at the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania before heading to Harvard and then Georgetown University.

Harvard lured him back once more last year for a dream job as the H. Naylor Fitzhugh Professor of Business Administration, and that’s when Morehouse came calling. The HBCU wanted a new president.

Was he interested?

Decades had passed since he’d fancied himself a president, but this was his chance.

In October, Thomas said yes, becoming the 12th president of the all-male college.

With both Yale and Columbia degrees, and tenure as a Harvard University professor with more than 20 years in the classroom, you’d think Thomas would’ve made peace with why his route to Morehouse was a circuitous one.

In some ways, he has. He’s grateful for having gotten through undergrad without a mountain of loan debt. But all these years later, he can’t help thinking what his life might have been had he made this stop at Morehouse first, and more recently, of the thousands of students who like him have to make the hard decision not to attend their preferred college because they, too, can’t afford tuition.

“I want there to be no more David Thomases,” he said.

That right there is the fuel feeding a historic capital campaign the president plans to launch soon to raise money for student scholarships and hopefully make the school less dependent on tuition for its fiscal health.

“In today’s environment, you can’t do what colleges did decades ago and keep raising tuition,” he said. “The public is not accepting of it nor are the parents who are making decisions about where to send their children.”

RELATED | Morehouse's new president discusses long to-do list

With tuition the only source of revenue, Thomas said, it becomes more and more difficult to not just offer scholarships, but to maintain a high-quality faculty and physical plant and secure the college’s future.

“That really requires us to build an endowment for our scholarships that will get to at least $200 million,” he said.

Plus, that will increase the college’s credit score and increase student access to Morehouse across the economic spectrum.

Ninety-five percent of Morehouse 2,175 students receive some type of financial aid.

Tuition at the private college is $24,565 ($47,952 including all costs), putting it far beyond many students’ reach.

But why a sleepover in the freshman dorm?

Since his term began on Jan. 1, 2018, Thomas had been asking his staff to put the experience of students first when making decisions and make the effort to provide consistent, reliable customer care. That includes quality food in the dining hall, responding quickly to concerns, and thinking of each other as customers.

“I wouldn’t call it service so much as care and providing it in a way that lets them know we care about them and respect them,” Thomas said.

Two nights at Graves Hall won’t likely cover the extraordinary scope of student life, but you have to appreciate Thomas’ efforts.

As president of this iconic place, the esteemed school he once dreamed of attending, he’s excited to be here. But he feels a certain heaviness, when he steps from his home, walks down the hill toward campus, and sees students crisscrossing the school yard.

He knows that one of them could be his MLK, the man in the black-and-white photo above his bed.

That means he has to get this right. If it means two nights in a freshman dorm, then so be it.

Find Gracie on Facebook (www.facebook.com/graciestaplesajc/) and Twitter (@GStaples_AJC) or email her at gstaples@ajc.com.