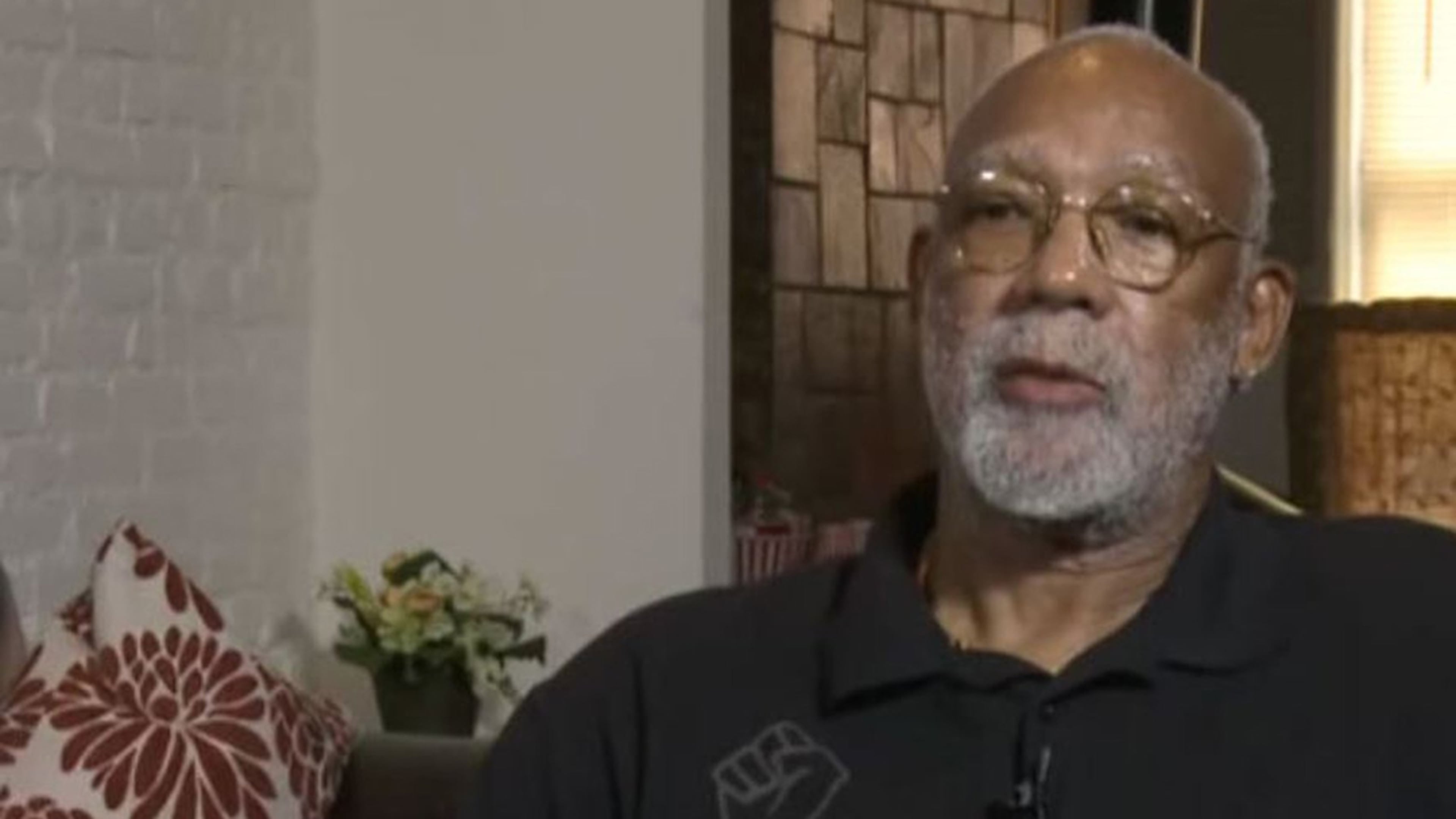

John Carlos, Olympian who raised fist in 1968, on “take a knee”

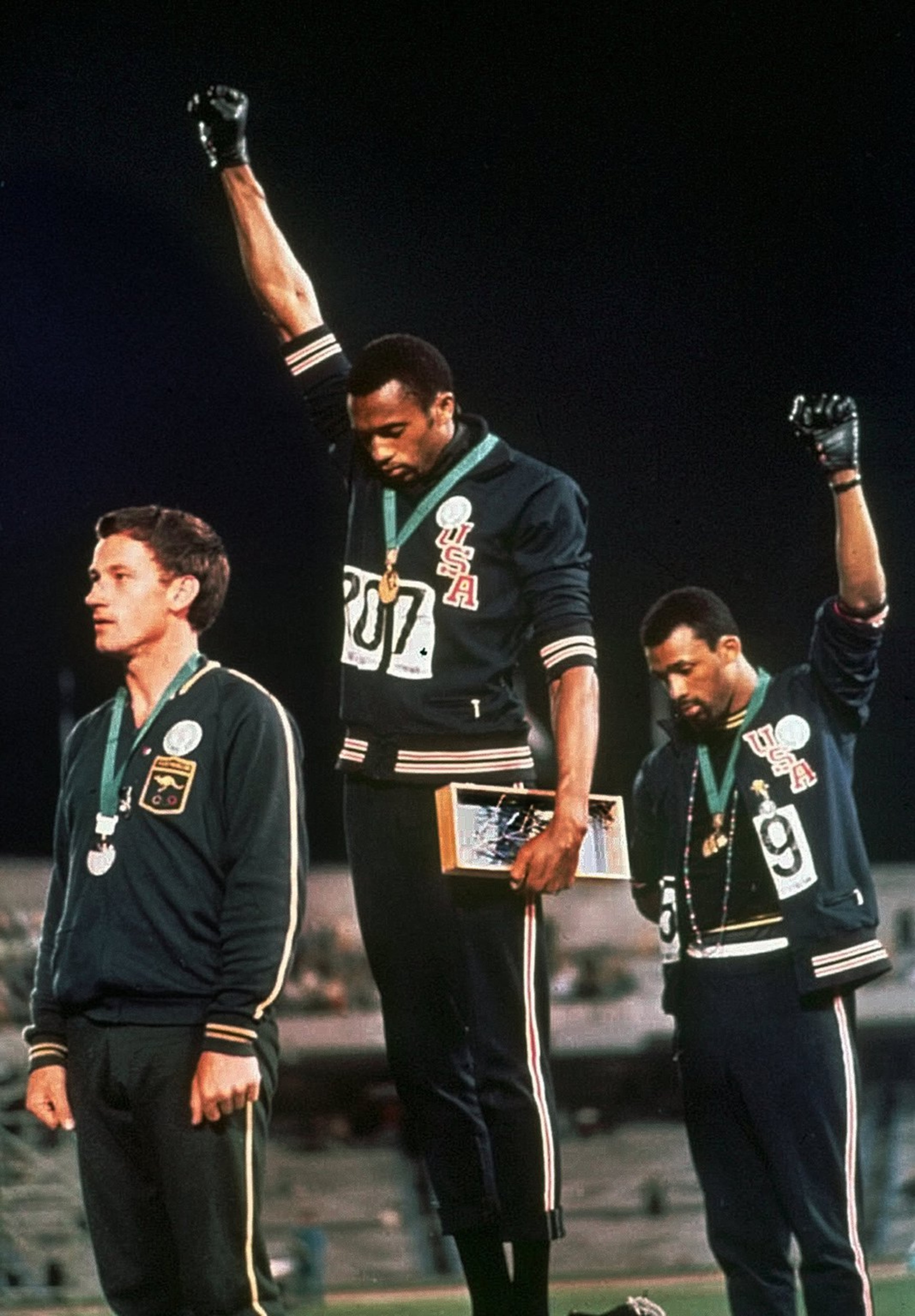

Nearly 50 years ago, it wasn’t a bent knee but a raised fist that shocked the nation.

John Carlos, then a bronze medalist in the 200 meters during the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, joined fellow American Olympian Tommie Smith in protesting the way blacks and others who were disenfranchised were treated in the United States.

They did so by raising their fists skyward in the black power salute.

It’s not unlike today’s controversy surrounding former San Francisco 49er Colin Kaepernick and other professional athletes who have taken a knee during the national anthem. Kaepernick was protesting police killings of African-Americans.

President Donald Trump has blasted those National Football League players who take a knee. During a recent rally in Alabama for Republican U.S. Senate candidate Luther Strange, the president said NFL owners should respond by saying: “Get that son of a bitch off the field right now, he’s fired. He’s fired!”

Trump others say the players are showing disrespect for the flag, the country and the military.

Carlos said the gesture was for all human rights.

“We were tired of being second-class citizens,” said Carlos, 72. “We were tired of the living conditions, tired of drugs running through the neighborhood — they weren’t going through Beverly Hills and Malibu. They were going through Harlem and the South Side of Chicago. We were tired of the housing situation in terms of blacks getting decent housing, and we were tired of the police harassing black people.”

Smith could not be reached for comment. Peter Norman, of Australia, who won the silver, wanted to show his solidarity. He wore an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge. Norman faced scorn when he returned to Australia, which was also dealing with criticism for its treatment of Aboriginals. He died in 2006.

It was a turbulent time in the United States. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. had been gunned down that April as he stood on the balcony of a Memphis hotel. His assassination was followed by riots and protests across the country. Opposition to the Vietnam War was growing.

Carlos, who now lives in Clayton County, remembers that moment vividly and the firestorm that followed.

He said he and Smith had talked about a way to protest what was happening at home. That moment came while on the podium.

Carlos said people in the stadium had started to applaud. That stopped when he and Smith bowed their heads and raised their fists.

“There was a deafening silence,” he said. “Everybody was stunned. Then they started screaming. They were going to shove it down our throats.”

International Olympic Committee President Avery Brundage criticized the athletes’ actions, which he called “outrageous.”

According to an article in The New York Times, the two athletes were told “that they must leave the Olympic Village. Their credentials also were taken away, which made it mandatory for them to leave Mexico within 48 hours.”

It wasn’t any better when Carlos returned to the states, where he said he and his family went through hell.

There were threats. He was investigated by authorities. His children were targeted by faculty members once it became known Carlos was their father.

“Let me tell you something, when you make a statement for humanity, you become this sacrificial lamb,” said Carlos, who later played professional football. “Your life is already secondary to the image you want to leave. They could take my life, but they could never erase that image. Once it’s done, it’s done and you’ve got to live with it.”

Related:

The Rev. Timothy McDonald III, the senior pastor of First Iconium Baptist Church, remembers that day well. He was a 14-year-old student and member of the Youth Black Panther Party in Brunswick.

“It was the talk of the town,” McDonald said. “Did you see? Did you see? Yes, I saw.”

That moment “symbolized the kind of pride that was different than anything else,” he said. “The intersection of athletics and politics goes back a long way. That point in history sent a loud message to America — not just black America — but to all America that we’re here, we matter and we make a difference.”

Gold medalist Mel Pender Jr. was also on the U.S. team in 1968.

Pender, 79, who lives in Kennesaw, roomed with Carlos.

He was in the military at the time, and while he didn’t participate in that protest, he understood the aim.

“Here we are representing our country, winning gold medals for America, and when we go home we don’t have the same privileges and opportunities as whites and it’s still that way,” he said. He considers the United States “one of the greatest countries in the world,” but he is bothered by the reaction to Kaepernick, who was trying to make a statement with a peaceful protest.

“This is America, but we have police brutality in this country and we have discrimination in this country,” said Pender, who co-authored a book, “Expression of Hope: The Mel Pender Story,” with his wife, Debbie. “I still want to see everybody live in harmony, but I have to wonder, will it ever happen?”

Today, Carlos is a staunch defender of those other athletes who are taking a knee during the anthem. He’s also spoken out in support of Black Lives Matter.

He said he would “definitely” take a knee today. It’s not about a “piece of cloth, it’s about the social injustices in society and the inequities of black people in this country.”

He criticized Trump’s comments about those who are taking a knee. He said Trump ran a divisive campaign and has done little since he’s been in office to build unity.

“Donald Trump is playing with people’s lives,” he said. “It’s the same rhetoric he used during the campaign. As a black man, my kids can go out to play and not come home. A black woman can drive through Texas and not come home. White people don’t have to worry about that. Everything changes in time, but the oppression hasn’t changed.”

He said before Trump questions anyone’s patriotism, he wants to see his discharge papers from the military.

“I demand to see his sons’ discharge papers from the military,” Carlos said. “I demand his daddy’s discharge papers.”

Carlos added: “People need to find their moral compass. You can’t be neutral anymore. You have to step up.”

Once you do, though, he said “the haters will come out to discredit you and lambaste you.”