A caretaker’s dilemma

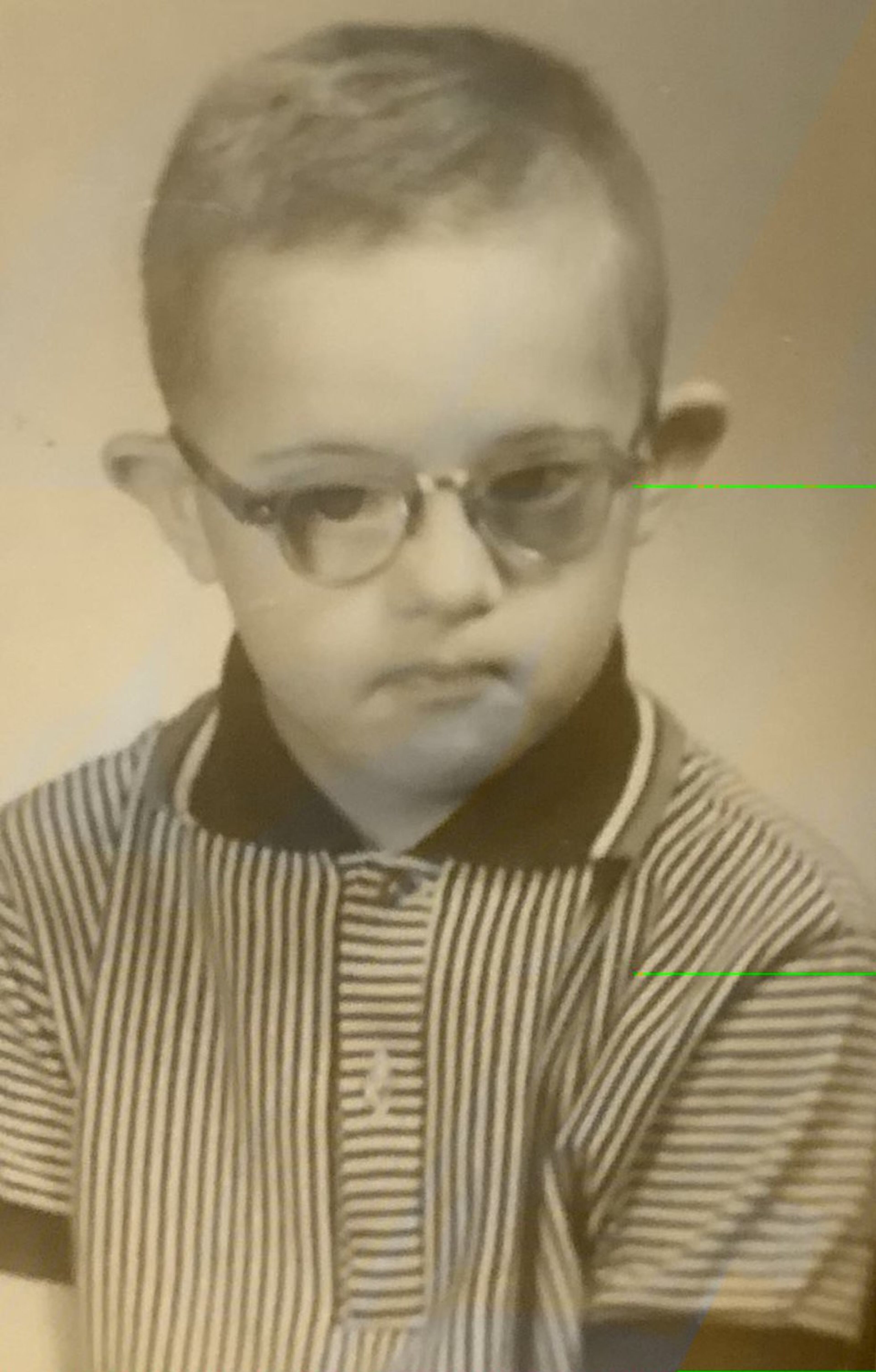

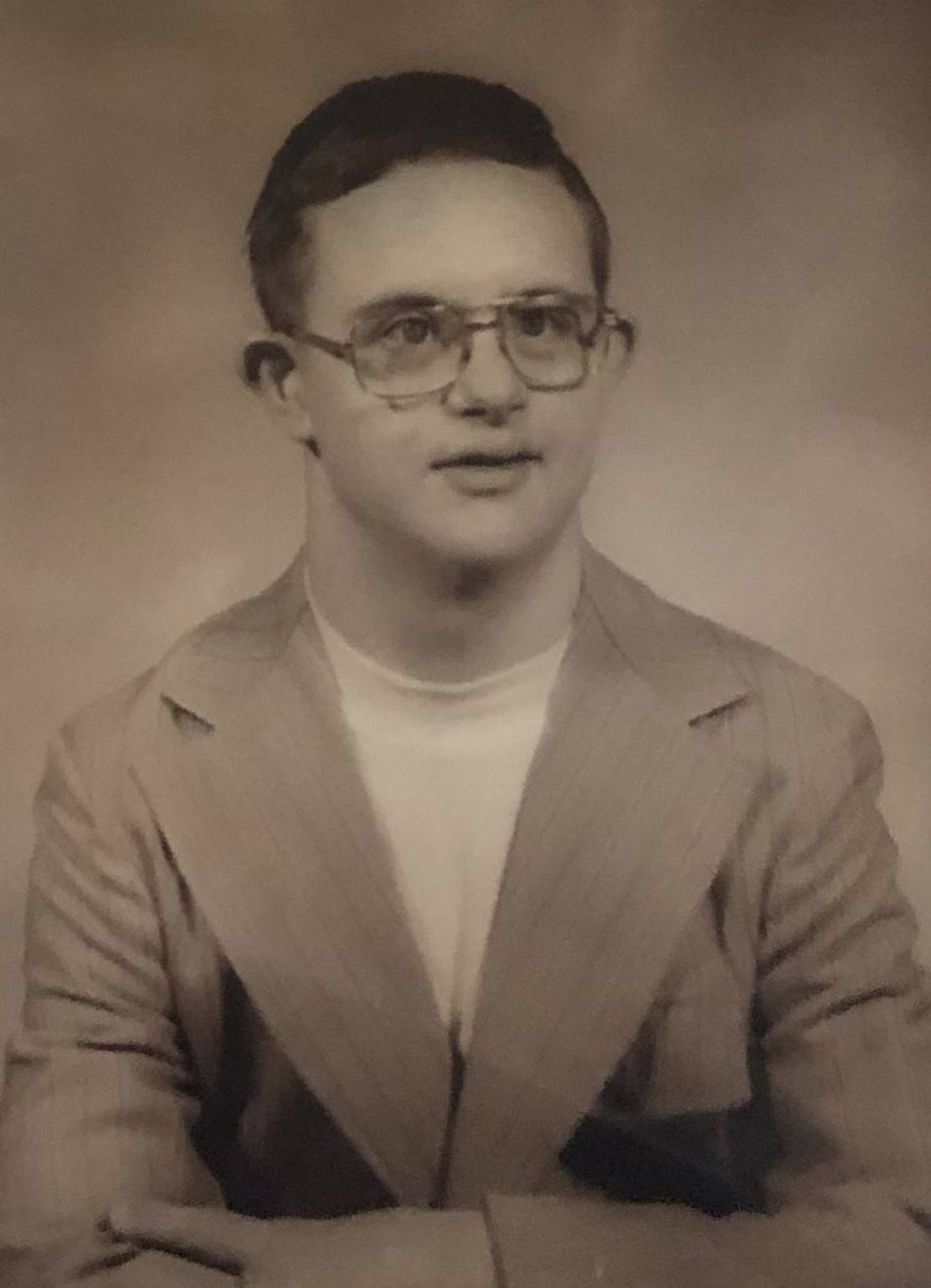

Hoke Edward “Ed” Benton, 68, sat in a recliner in a sun-splashed bedroom, studying the covers of DVDs he held close to his face. The large television played a 1997 Lawrence Welk special, the same show he’s watched every day for more than 16 years — a program his cousin and longtime caretaker, Julianne Jones, describes as “his form of prayer.”

But Benton, who has Down syndrome, peered up through his thick glasses and reached out for a hug when she entered the room. He stroked her arm. The red Santa Claus T-shirt he wore was emblazoned with the phrase “Don’t stop believing,” words Jones, 73, clings to now.

This visit was over the holidays, before coronavirus and social distancing took hold, forcing Jones to stay away. She hasn’t returned since March 14.

“I was seeing him about every third day,” she said recently. “Not being able to do that, it’s just killing me.”

For more than 15 years, Jones cared for Benton in her Douglasville, Georgia, home. He was a fixture by her side. Then, last fall, her cousin’s mounting physical problems — which grew after a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease two years ago — forced her to scramble for an alternative. The care she found was temporary, though, as she only had enough money to fund it through the spring.

If she couldn’t find a new way to support him, Jones feared earlier this year, her cousin would become a ward of the state and end up in a nursing home that wouldn’t give him the quality of life he deserves or understand his needs and would be too far away for her to see him.

“I’m terrified I’m going to lose him,” Jones said at the time. “And he can’t speak for himself.”

>> READ | Opinion: Act now to help elderly, care homes in COVID-19 fight

Now, given the COVID-19 pandemic, she can’t move him at all — adding one more twist to an already tangled story.

Benton is part of the first generation of people with Down syndrome who are reaching old age, experiencing new joys and rites of passage. But their newfound longevity is ushering in a host of challenges, including higher rates of physical health issues and dementia. As they begin to outlive their parents, many families are grappling with devastating questions: Who will care for them? And how will they pay for it?

‘Still in there’

He was full of mischief when they were small. He pulled her hair, yanked off her necklaces and rammed her with his tricycle. Still, Jones’ younger cousin taught her all she needed to know about patience and tenderness.

In spite of his poor vision and 70 IQ, Benton learned to read and write. He was a history buff who could name all the presidents, the states and their capitals, and rattle off Civil War trivia. He was valedictorian of his class at the Atlanta-area school he attended for children with developmental and intellectual disabilities. Jones opened up a scrapbook to share a lengthy poem he copied in cursive around that time.

“What will I do and what will I be, when I’ve grown so tall that I’m all of me,” Benton wrote, though we’ve added punctuation for clarity. “Will I be a pilot or maybe a diver? A singer, an actor, a taxicab driver? Perhaps a doctor who cures cuts and ills, or a druggist with shelves of bottles and pills?”

This poem, which goes on to fill a notebook page, gets to Jones every time she reads it, she said, her eyes welling up.

“I know he is still in there with all the dreams and hopes that we all have,” she said. “Most people don’t see that.”

Living longer

Each year, some 6,000 babies are born in the U.S. with Down syndrome, the most common chromosomal disorder, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The total number of people now living with the genetic disorder in the U.S. is unknown, but it’s well more than 400,000, according to the Global Down Syndrome Foundation.

The average lifespan for someone with Down syndrome in 1960 was 10 years. That shot up to 30 in the 1980s and more than 47 by 2007, The Journal for Pediatrics reported. Now, the average life expectancy is 60, with many people living well beyond that age, according to the National Association for Down Syndrome.

Advances in medicine explain some of this longevity. But society has changed too: Children aren’t cut off from their families and hidden away like they once were.

“I can guarantee you that when (Benton) was born, a doctor recommended that he be institutionalized,” said Sheryl Arno, executive director of the Down Syndrome Association of Atlanta. (Jones confirms that’s true.) “Ed’s parents did everything right. They were involved in his life, kept him at home,” and likely never believed he’d outlive them, Arno said.

Individuals with Down syndrome carry the gene that produces a protein in the brain that’s linked to Alzheimer’s. The National Down Syndrome Society says, as a result, about half of those who reach 60 will have the disease. This leaves people like Jones struggling to figure out long-term care options for loved ones, a concern that’s become universal as Americans age.

“We use the phrase, ‘We’re more alike than different,’” said David Tolleson, executive director of the advocacy group National Down Syndrome Congress. “This is one case where it’s absolutely true.”

A plan for care

Benton’s father, a carpet layer and war veteran, died in 1986. When Benton’s mother entered a nursing home in 2004, two years before her death, she came up with a plan for her son, an only child.

Jones, a divorced mother of grown children who’d retired after 27 years from BellSouth, promised to execute the plan and look out for her cousin. She became Benton’s power of attorney for health care and took control of two trusts to meet his needs.

One, a restricted fund to supplement the survivor benefits he gets from his father’s Social Security, offered $800 a month, but that ran out in 2009. The other, a special needs trust in the amount of $318,000 (only made possible thanks to a family inheritance), has dwindled over the years — after being used for Benton’s transportation, activities, clothing, food, medical costs, special tests and more.

Up until last summer, the two cousins were getting by, even if they couldn’t be as active as they once were. Gone were the days when they bowled every Saturday, traveled for the Special Olympics and took tai chi classes.

Benton, a country music fan, amassed DVDs and CDs. Every Friday, they went to Walmart so he could pick up the latest issue of Country Weekly. For a long time, he wore only black in homage to Johnny Cash, before adopting a wardrobe of Hulk superhero T-shirts. For 10 years in a row, at his insistence, Jones dressed him up as the Hulk for Halloween.

He loved politics and sat with Jones to watch debates. He never did register to vote, though, she said, “because if you asked him who he wanted to vote for, he’d say Bill Clinton, even though he wasn’t running.”

Benton drew pictures, and she shaded in the colors. They used nicknames for each other. She called him Leroy; he called her Turkey Butt. Every night, they said their prayers together.

A rapid decline

Starting a couple of years ago, Benton’s health began to decline. He had digestive issues and gallbladder problems. He was diagnosed with osteoporosis. He asked where the bathroom was at home, a first sign of his dementia. He stopped recognizing people in photographs, repeated questions and, most worrisome to Jones, started wandering in the middle of the night.

Benton, who is legally blind, had long been prone to stumbles and twisted ankles. But his gait got worse. He was admitted to the hospital last July with a dislocated patella, or knee cap. An initial attempt to put the patella back in place failed, and in the weeks that dragged on at the hospital, Benton developed a urinary tract infection, double pneumonia and bad reactions to medications. Doctors gave up on fixing his knee and put him in a steel leg brace that gave him blisters.

Already incontinent, now Benton couldn’t walk or lift himself out of a chair or bed. He was uncomfortable, in pain and grew embarrassed when strange women changed his diaper. The hospital labeled him “combative” and pushed for his discharge. Social workers pressured Jones to move him to a nursing home but gave only three options, each 100 miles away. Instead, she brought Benton home again.

She pushed a cot up against a hospital bed in her living room, so she could sleep next to him. Benton still managed to fall during the night and got his arm caught in the railing. The fire department had to take the bed apart to free him.

That led to another hospital visit. Then came a third, after Benton crumbled to the pavement after getting out of Jones’ car, forcing her to dial 911. She says she was told, more than once, that doctors wouldn’t help Benton further because he “has no quality of life.”

She sobbed and demanded, “What am I supposed to do, take him to the vet and put him to sleep?”

A temporary answer

Unable to handle Benton’s growing needs, Jones found a temporary solution in a cozy private personal care home, 35 miles away, close enough for her to make regular visits. The owner, Jeremy Le, 35, established Albert’s House, a small private business that caters to those who are hard to place, need extra attention and may not thrive in other settings.

He took Benton in, Jones said, when no one else would — in part because her cousin had been branded “combative.” Le, who calls Benton “an angel,” figured the least he could do is offer a month’s respite care, giving Jones a needed break and time to figure out a long-term plan. That was in October, and Benton’s never left.

The house has bedrooms for three residents, and the all-inclusive costs start at $8,000 a month. It was meant to be a stopgap, but Jones has since blown through Benton’s trust money while battling bureaucrats to get permanent help.

She originally set out to get him government assistance through a Medicaid waiver program that covers residential care for people with developmental or intellectual disabilities. But the obstacles kept coming, the paperwork didn’t stop, and her desperate calls were met with non-answers.

Le, who’s reached out to multiple experts to try to help, is no less confounded.

“I still don’t know how the hell to figure this out, and I’m generally pretty resourceful and savvy,” he said a couple of months ago. “I’m baffled that this isn’t discussed more often. I think about Julianne and wonder, ‘How is she supposed to navigate this?’”

She’s given up on that waiver. Even if Benton was deemed eligible, he wouldn’t have gotten it before the money ran out. That’s because there are 6,000 other people in Georgia who are on the same list seeking similar services, according to the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities, and he’d need to be prioritized to the top.

>> READ | Controversy over Georgia mental health budget as needs grow

The odds of that grew slimmer as state lawmakers debated proposed budget cuts, including the possible elimination of new waivers, before the coronavirus caused the Legislature to suspend its session.

Georgia is far from alone in having long waiting lists, and it’s not the only state that’s sought to cap new waiver slots, said Ashley Helsing, director of government relations for the National Down Syndrome Society.

“The whole system is just outdated and not set up for people with disabilities,” Helsing said.

What’s next

The state could be forced to step up and pay for Benton, if he was declared homeless. The way that might work, Le explained, is an ambulance could take Benton to a hospital and then Jones would have to say she can’t care for him. But that could mean relinquishing control of where her cousin lands, a prospect Jones can’t stomach. She made a promise to his mother, after all, that she’d look out for him.

The trust established to assist with Benton’s care, in the end, may have complicated matters. Jones was told that until that money was depleted, he — and, by extension, she — couldn’t be helped with services. And so, Jones rushed to spend every penny. She shopped for supplies, scheduled home improvements and paid Le to keep Benton through May.

“They were using the trust as an excuse not to go forward, and now they don’t have that excuse anymore,” she said in late March.

The bedroom where Benton once slept is stockpiled with purchases including adult diapers, sets of sheets and a collection of pureed foods, since Benton has no upper teeth, juices and treats with extra protein.

She ordered new gray vinyl floors, to replace the old carpet in the living room, which trapped smells each time Benton had an accident. The new floors can be easily cleaned and are strong enough to withstand a hospital bed with wheels — which she can’t yet order, when coronavirus makes the supply of them a premium.

The plan was to bring Benton home in April, but until isolation orders are lifted, he can’t move. She’s talked to him on the phone a few times, but she doesn’t want to excite or confuse him. She doesn’t know if understands why she stopped visiting.

“I just want to hold him so bad and explain to him what’s going on, and I can’t do it,” she said.

That he remains in the home’s care offers some relief to Jones, even as it pains her that she can’t see him.

“They’re going to do a better job with him than I could,” she said.

The best hope for Jones, once she has him back, is to get a different sort of waiver, one that will help her get in-home assistance.

When Benton was still with her she hired someone to stay with him a four hours a week while she ran out for groceries and other errands. Now, given his growing needs, she says she’ll take as many hours of help as she can get, ideally “one day for errands, one night for sleep.”

But is that waiver for in-home help even guaranteed? If it is, how long will it take to secure? What happens when her cousin falls next? Or if Jones becomes sick, her back goes out, or worse?

“If something were to happen to me, he’d be laying there … with nobody to check on him,” she said, through tears. “But I don’t think Ed has a chance of getting any kind of waiver until he’s home, and I begin to beg again.”

Jessica Ravitz is a freelance journalist based in Atlanta. Learn more about her at www.jessicaravitz.com.

A version of this story was originally produced by MemoryWell News for the Ages, a news site for and about family caregivers.