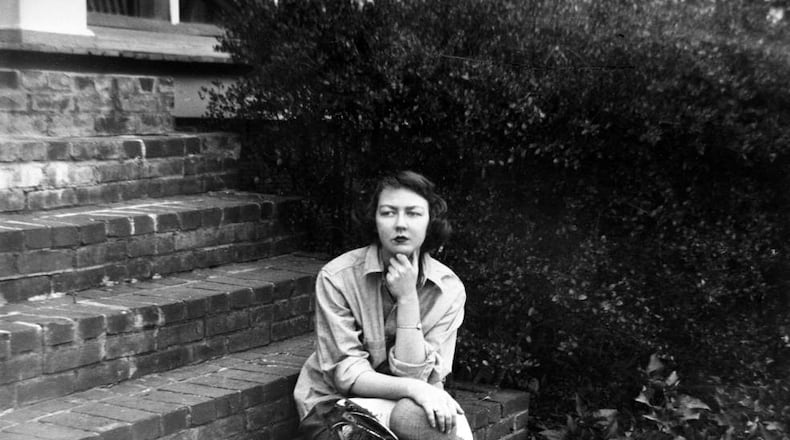

A new documentary film about one of Georgia’s most eminent writers, Flannery O’Connor, will have its digital premiere online Friday, July 17.

“Flannery: The Storied Life of the Writer from Georgia,” includes interviews with many friends and colleagues of O’Connor who are no longer living. Chief among these is Sally Fitzgerald, who edited O’Connor’s letters for the collection “A Habit of Being” and who worked for decades on an O’Connor biography.

As a young writer, O’Connor stayed for a year and a half with Sally and Robert Fitzgerald in a garage apartment at their house in Ridgefield, Conn., while O’Connor wrote the beginning of “Wise Blood” and other stories.

Her hostess determined that O’Connor was a “formidable talent” and from that time forward their lives were twined together. Few knew more about O’Connor than Fitzgerald.

Fitzgerald died 20 years ago this month, her O’Connor biography still unfinished.

“Flannery” the film includes excerpts from a three-hour interview with Fitzgerald conducted by filmmaker Chris O’Hare in the late 1990s. Listed as one of three executive producers, O’Hare shared those interviews with co-directors Elizabeth Coffman and Mark Bosco. Scholars, said Coffman, “will go crazy” for that information, and for a possible extended version.

“We’ve been given permission to make a second kind of film that would have more interviews,” said Bosco, a Jesuit priest and vice president for mission and ministry at Georgetown University.

Other significant interviews include talks with O’Connor’s good friend the late William Sessions -- also an O’Connor scholar and a Georgia State University professor -- and with O’Connor’s publisher, the late Robert Giroux.

All of these voices open a window into the life of O’Connor that had been closed by death. Also, because the filmmakers had the cooperation and support of the Mary Flannery O’Connor Trust, they were able to incorporate passages from her writing in the film.

“I personally really resent documentaries about writers that don’t include some of their story-telling,” said Coffman. “From the beginning I wanted to include excerpts from her fiction.”

The trust was not willing to allow any re-enactment of O’Connor stories, but did allow voice-over from actor Mary Steenburgen, which the filmmakers paired with motion graphics. Animated characters, some of them grotesque, act out scenes from such stories as “A Good Man is Hard to Find.”

“This was a compromise,” said Bosco. “I think the trust is pleased with the results. We were the first people they gave the rights to the archives, to quote from Flannery.”

These scenes are incorporated into a portrait of the Middle Georgia world which O’Connor rebelled against and which she dissected in her fiction, but which also shaped her sensibilities.

A new book by Angela Alaimo O’Donnell, “Radical Ambivalence,” and recent essays in the New Yorker and the The Bitter Southerner have re-examined O’Connor’s attitudes toward race, her treatment of the African American characters in her stories, and the sometimes-racist language in her private correspondence.

The film is a view into this time, as the Jim Crow south was being dismantled, said Bosco. “I think the film tries to lay it out fairly and squarely.” Despite her racist language, she was aware of the imbalance in the world, and “her stories were almost always interrogating her position,” he said.

Last fall and winter “Flannery” made an appearance at several film festivals, before the pandemic “cut our film festival parade short,” said Coffman. The Atlanta Film Festival, canceled, along with everything else this summer, “was one of the big ones we were looking forward to.”

Instead, viewers can buy a virtual ticket to the movie at the Atlanta Film Festival site. Part of those proceeds will go to help support the festival, which has postponed its events until September.

In addition to the film, the filmmakers are hosting four different online discussions of issues that are critical to O’Connor’s life and work. Each will take place at 6 p.m. on the next four Mondays.

At 6 p.m. on Monday, July 20, the filmmakers will oversee a panel on race at the “Flannery” Facebook page.

On Monday, July 27 a panel will discuss faith. On Monday, Aug. 3, they will host a discussion of disability, a topic that affected O’Connor throughout her adulthood. She was a victim of lupus, which finally took her life in 1964.

On Monday, Aug. 10, there will be a discussion of craft.

All discussions will allow audience members to pose questions to the panels in real time through the chat function.

For more information go to flanneryfilm.com

About the Author

The Latest

Featured