Atlanta in the 1960s has been described as an overgrown small town, but in the 1970s Atlanta stepped through the looking glass.

Professional basketball and hockey arrived, along with a brand-new music venue at the Omni Coliseum; Atlanta’s first Black mayor was elected; the city built the world’s tallest hotel, welcomed a rapid transit system and a new international airport, along with some big-city worries. (Atlanta was the murder capital of the U.S. in 1973.)

Another major change occurred during that decade: The city became a magnet for gay and lesbian transplants from elsewhere in the South, who came seeking a more accepting environment.

That new demographic gave rise to two new phenomena: A vibrant gay rights movement and the proliferation of gay nightclubs offering elaborate shows by female impersonators.

A new history of the period by Martin Padgett, “A Night at the Sweet Gum Head: Drag, Drugs, Disco and Atlanta’s Gay Revolution” was mostly written while he was pursuing a Master of fine arts degree at the University of Georgia. It follows a broad cast of characters, but focuses on two men, activist Bill Smith and drag artist John Greenwell.

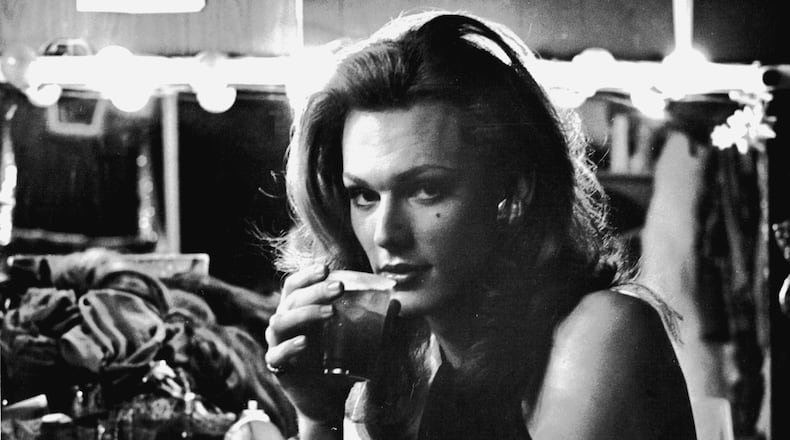

Credit: Courtesy: Martin Padgett

Credit: Courtesy: Martin Padgett

Greenwell, who would eventually win a national title for his drag performances as Rachel Wells, came to Atlanta from Huntsville, Alabama, in 1971, and perfected his act at a scruffy Cheshire Bridge Road club called the Sweet Gum Head.

Smith campaigned through his influential gay newspaper, The Barb, and from inside city politics as a member of the Community Relations Council, fighting to reduce police harassment of homosexuals and to prompt the city to pass gay rights legislation.

Padgett weaves together these overlapping story lines, while crafting a portrait of the wild and wooly Atlanta of the 1970s, when the crickets of a thousand back yards gave way to the pounding 4/4 beat of Donna Summer and Gloria Gaynor.

Credit: Susan W. Raines

Credit: Susan W. Raines

The book offers dozens of cameos, including such personalities as Burt Reynolds, in town to kick-start Georgia’s film industry, and RuPaul Charles, who moved to Atlanta at age 15 and found his niche in drag. RuPaul would eventually turn the art of drag into nationally televised entertainment.

Then there are the drag performers — among them Charlie Brown, Satyn DeVille, Lavita Allen and Diamond Lil. If Padgett offers overgenerous detail about the frothy songs and costumes at the Sweet Gum Head nightclub, he explains in the introduction that these safe places, gay bars and nightclubs, were pivotal, “the birthplace of the emerging gay rights movement.”

It was the community that coalesced around clubs that swelled the Pride Day parades and also took to the streets to protest Anita Bryant and her “Save Our Children” anti-gay movement, Padgett said.

“From day one there has been a division between achieving queer rights through assimilation versus radicalism,” said Padgett in an interview from his Toco Hill home. “There has always been that tussle. Well, the drag queens won.”

Drag, said Padgett, led the “queer civil rights movement,” not just by providing a safe place for gay Atlanta to gather, but also by attracting those outside the community.

“There’s this entertainment factor,” said Padgett. “It can draw in straight people who might not be allies but are curious. It’s bringing people into a room together who might not understand each other. It’s a powerful community creator, as well as an art form, especially in Atlanta.”

Credit: Courtesy: W.W. Norton

Credit: Courtesy: W.W. Norton

In the meantime Bill Smith, who shielded his sexuality from his parents by maintaining a usually Platonic relationship with girlfriend Diane Hughes, represented a different approach.

Copying the tactics of the civil rights movement, he led the Gay Liberation Front, helped organize the city’s first Gay Pride march in 1971, organized protest gatherings, urged boycotts, wrote editorials and presented demands to the new African American mayor Maynard Jackson.

But behind his suit-and-tie appearance, Smith was living on the edge, abusing prescription drugs and operating a male escort service. He died March 9, 1980, of an overdose of Placidyl.

All these events happened long before Padgett, 51, arrived in Atlanta. He was born and raised in Washington, D.C., and lived in Birmingham, Alabama, as a young man, making frequent trips to Atlanta to experiment with visits to gay clubs.

When he moved to Atlanta in 1997, at the age of 28, he was still hiding his sexuality from the world, but reasoned “If it’s not going to happen here, it’s not going to happen anywhere.”

To tell Smith’s story Padgett hunted down relatives and friends as far away as Japan. He found copies of The Barb at the Atlanta History Center, the University of California, Davis, and Cornell University. Diane Hughes shared some of Smith’s letters and sat for lengthy interviews.

Greenwell’s history was easier to document. The performer had published a memoir online, and Padgett found him living in Kentucky, having left the drag life behind.

The manuscript eventually grew unwieldy and Padgett had to cut some marvelous scenes, including a charity boxing match between Maynard Jackson (in flowered trunks) and Muhammad Ali.

He wrote a long portrait of diminutive Leslie Jordan, who would later reach fame in television’s “Will & Grace” but got his start as a drag performer at the Sweet Gum Head. The bit was excised, but resurrected in an issue of The Bitter Southerner.

This history of the gay revolution begins with the happy crescendo of a disco anthem. Padgett ends his history in 1981, as scientists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puzzle over a rare form of cancer that affects gay men.

That was the tragic advent of the AIDS crisis, a disease that would take 100,000 victims before the decade was over and would threaten to destroy the community and all the political progress of the previous decade.

Padgett, now a Ph.D. candidate in history at Georgia State University, said he may explore that next chapter. But he writes that he hopes that this tale “reclaims some of the joy and optimism of that brief time.”

Coming Sunday

Atlanta’s first gay pride march, on June 27,1971, was virtually unrecognizable from the 300,000-person, multi-day celebration it has become in recent years.

The event was a turning point, a moment when, for the first time, the LGTBQ community could publicly celebrate a part of themselves that society had long demanded they keep hidden.

See full story on Sunday A1.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured