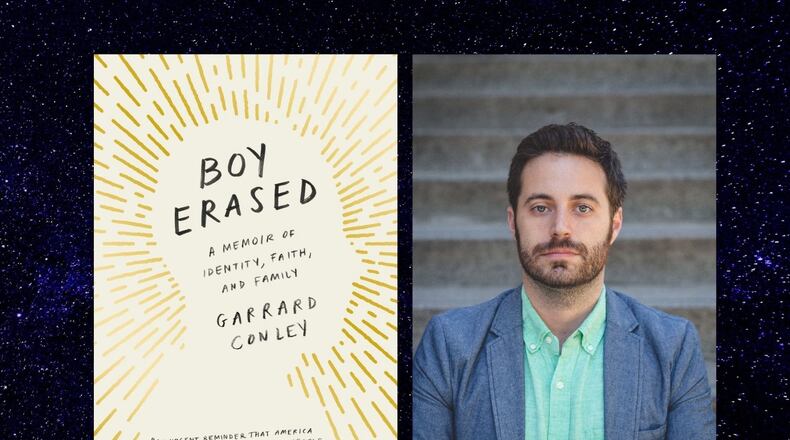

Banning a book usually extends its influence. For House Bill 4979, Texas Rep. Matt Krause compiled a list of 850 books to be removed from public and school libraries. One of the titles is “Boy Erased: A Memoir of Identity, Faith and Family” by Garrard Conley, who recounts his harrowing experiences with conversion therapy to “cure” his homosexuality. (Spoiler alert: It failed.)

“I was not shocked to see my book on the list,” Conley says, “though I did find it a bit funny given the fact that the main message in my memoir is one of compassion, which stemmed from my understanding of Christ’s life. I apply compassion to my parents, my community, even my counselors who performed conversion therapy on me. My parents are compassionate people who made a mistake. But, of course, none of these people making banned books lists actually read. They are not interested in context or content; they are interested in cheap signaling.”

The signaling flagged MSNBC commentator Ali Velshi, who had the author on national television recently for a lengthy interview about the book and the movie it inspired, starring Russell Crowe and Nicole Kidman. Conley — warm, modest, respectful — is his own best pitch-man. Sales of the 2016 book soared. Sorry, Rep. Krause.

“I find this banned-books list to be incredibly stupid, and I imagine many people do, but incredibly stupid things can also be dangerous,” Conley says. “Conversion therapy seems like a joke to anyone who hasn’t been involved with it, but it kills people every year.”

An assistant professor of creative writing at Kennesaw State University (KSU), Conley, 37, is the incoming executive director of the Georgia Writers Association (GWA), which oversees the Georgia Author of the Year Awards and hosts other events and classes, as well as the Red Clay Writers Conference.

About GWA, “I really like the direction the group has been going in, in sharing voices that we hadn’t heard from,” he says.

Conley identifies the John Lewis Writing Grant, which just announced open submissions, as a step in the right direction. The program awards a $500 grant to a Black Georgia writer to give a public reading or workshop presentation and includes a scholarship to the Red Clay Writers Conference. For details go to www.georgiawriters.org.

Conley, who moved from New York City to Atlanta during the pandemic, doesn’t officially take over GWA until Aug. 18, but his first goal will be to convene in-person events that were cancelled during the COVID-19 shutdown.

“I want us to get our physical presence back, with better networking between individual writers and strengthened ties among universities. We need to build more partnerships.”

He’s considering moving the Red Clay Writers Conference from fall to spring, but hasn’t made any decisions yet.

“I will be assembling a team,” he says. “I don’t like to make decisions unilaterally, so I haven’t set up anything yet. I’m hiring interns next week.”

Meanwhile, Conley recently visited Andalusia, home of the late Flannery O’Connor in Milledgeville, and he is looking forward to reading more books by Georgia authors.

“One reason I came to KSU was Tony Grooms, whose writing I had always admired, and he has proved very generous and helpful since I arrived.”

Grooms — an author, fellow professor of creative writing and director of the M.A. in professional writing program at KSU — returns the sentiment.

“Garrard Conley is as charming as he is talented,” says Grooms. “He is well-connected in national publishing circles and is an absolute gift to Georgia’s writing community. As director of Georgia Writers, he will bring new ideas and expand the reach of the organization. As a professor of writing at Kennesaw State University, he will be deeply involved in training the next generation of Georgia writers.”

Conley wanted to be a writer since he was 9 years old. He was an only child in a close-knit, devout family in a small town in Arkansas. His father is a Baptist preacher. When someone “outed” Conley to his parents, he was given the ultimatum of exile or conversion therapy. So he enrolled, with earnest determination, in a group called Love in Action that promised a path to heterosexuality.

“Most of us have that uncle at the dinner table,” Conley says. “The one who says offensive things and laughs? Like, ‘What’s next? Marrying your dog?’ Well, conversion therapy is like if that uncle developed a program for his outrageous theories.”

Conley and other LGBTQ people, grouped together with people identified as pedophiles, adulterers and alcoholics, endured a program loosely based on 12 Steps with dashes of Freud, featuring confessions and moral inventories. Alumni of conversion therapy often joke that if you are not queer when you go in, you will be when you leave. One assumption these places make is that gay men have not been adequately exposed to sports, so watching fit jocks flex their muscles was part of the therapy.

“I don’t think seeing good-looking men in tight outfits was having the intended effect!” says Conley.

While in the program, Conley kept notes, but counselors threw them away. The only books he was allowed to read were Christian fundamentalist texts. No secular novels, no yoga, no Dungeons & Dungeons and no “Harry Potter,” one of his guilty pleasures.

A small-town boy who wanted to be a citizen of the world, Conley studied at Auburn and joined the Peace Corps for three years, teaching English and HIV/AIDS awareness in western Ukraine. He earned an MFA from Brooklyn College, where he was a Truman Capote Fellow, and he received an MA in English from Auburn. He also did something spontaneous in his personal life: “I fell in love with a Bulgarian man and lived in Bulgaria for a while.”

Now happily married, Conley and his parents have made peace, and he dedicated his book to them. He speaks around the country about conversion therapy, and runs, with friend David Craig, the podcast UnErased on the subject.

“What impresses me to this day about my friend is his grace,” Craig says about Conley. “There are many people in his life that have done him wrong, not putting his feelings or interests ahead of their own, and he has always led with thought and compassion, forgiving those who have hurt him, educating and advocating along the way.”

Conley remains optimistic despite the persistence of the therapy.

“The more you try to control someone’s heart and body, the more that person is going to resist, to be even more expressive, to win in the end.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured