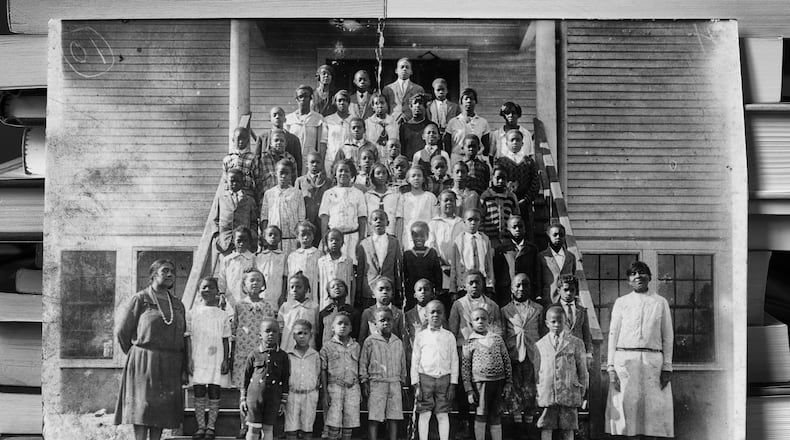

Hidden all over the South are structures that once powered a renaissance in Black America.

Some are modest, two-room clapboard structures. Others are three-story brick buildings.

All were built through a unique partnership between white mail-order magnate Julius Rosenwald and Black educator and leader Booker T. Washington.

Urged by his friend Washington to help the Black community educate its children, Rosenwald, from 1912 to 1932, helped fund the construction of almost 5,000 schools for Black children around the South, schools that lifted generations of African Americans out of poverty.

Rosenwald, president and part-owner of Sears, Roebuck and Co., teamed with local communities, who contributed labor, materials and funds. Atlanta photographer Andrew Feiler discovered the Rosenwald story while working on another project, and was shocked that he hadn’t heard the name before.

Feiler is a fifth-generation Jewish Georgian, raised by politically active parents who worked for social justice. How had they not told him about Rosenwald, a Jewish philanthropist with an incalculable impact on the South? “This was my territory!” said Feiler.

Rosenwald and Washington’s program “dramatically transforms this country,” he told a recent virtual panel at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights. “It profoundly reshapes the African American experience, and yet its scope and sweep are largely unknown and remain hidden history.”

In 2014 Feiler set out to find and photograph the Rosenwald schools that still stand, and to bring the Rosenwald story into the light.

Credit: Andrew Feiler

Credit: Andrew Feiler

Today perhaps 500 of the buildings survive. At first Feiler planned a simple photo essay, but as he talked to graduates, the scope of the project grew, and he added history behind his images. He decided, he said, “I can’t NOT tell this story.”

Feiler’s photos and text became the volume called “A Better Life For Their Children: Julius Rosenwald, Booker T. Washington, and the 4,978 Schools That Changed America,” published this spring by the University of Georgia Press.

(See a gallery of images from “A Better Life for Their Children.”)

Twenty-three images from the book are also part of a new exhibit at the rights center. Feiler recently provided a tour of the exhibit, which features 20-by-30-inch prints of his black-and-white photos.

As Feiler marveled at seeing his name in two-foot-high letters on the exhibit wall, Calinda Lee, head of programs and exhibitions at the center, praised the scholarship and art that went into Feiler’s work.

Lee added that the center had been financially stressed during the year of COVID-19, and that Feiler helped make the exhibit possible. “Andrew was generous: he waived the venue fee, he had the pictures framed and mounted,” said Lee. “It’s a really important issue to understand: that Julius Rosenwald was a visionary philanthropist.”

Credit: Andrew Feiler

Credit: Andrew Feiler

The photograph inviting visitors into the exhibit is a portrait of the late U.S. Rep. John Lewis, who attended the Dunn’s Chapel School, a Rosenwald school next to the Dunn’s Chapel A.M.E. Church in Pike County, Ala.

Children educated at Rosenwald schools would, like Lewis, go on to power the civil rights movement. They included Medgar Evers, Mississippi field secretary for the NAACP who was later murdered for his activism; the poet and memoirist Maya Angelou, northern coordinator for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and a former student at an Arkansas Rosenwald school; and Lewis, who chaired the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, helped organize the 1963 March on Washington and was one of the original Freedom Riders.

Feiler captured Lewis’ portrait in the congressman’s Washington offices on Oct. 29, 2019. Two months later Lewis would announce that he had been diagnosed with stage IV pancreatic cancer.

Despite his illness, Lewis also wrote a forward for the book, stating, “Andrew Feiler’s photographs and stories bring us into the heart of the passion for education in black communities. The passion of teachers who taught multiple grades and dozens of students in a single classroom. The passion of parents and neighbors who helped to raise the money to build our schools and then each year continued to reach deep to purchase school supplies. The passions of students like me who craved learning, worked hard, and read as many books as we could put our hands on.”

There were 243 Rosenwald schools in 103 of Georgia’s 159 counties; 35,000 children attended these schools. The surviving schools in Georgia include the Hiram School in Paulding County, the Eleanor Roosevelt School in Warm Springs, the Friendship School in Chattahoochee County, the Sandersville Hill and Industrial School (now the T.J. Elder Community Center) and the Noble Hill School in Cassville. The latter is a humble, two-teacher structure, which was preserved and became a heritage center for Bartow County.

Credit: Andrew Feiler

Credit: Andrew Feiler

One of the first images in the book shows Sophia and Elroy Williams inside the Hopewell Rosenwald School, in Bastrop County, Texas. The couple are proudly holding an ornately-framed photograph of Sophia’s grandparents, Martin and Sophia McDonald.

Formerly enslaved, the McDonalds eventually acquired 1,200 acres in Bastrop County, and Sophia McDonald donated two acres for the Hopewell School. Sophia Williams’ mother was one of the first teachers there, and the younger Williams was eventually a student there.

In the photo, we see that the Williamses are bundled against the cold. They are posing in the unheated schoolhouse, which Elroy has been steadily repairing, re-roofing, and insulating, in preparation for its new life as a community center.

The first structures were, like the Hopewell School, two-room wooden structures. Later the schools were three-story brick buildings. They housed multiple classrooms with hundreds of children and employed up to 18 teachers.

Feiler points out that the Rosenwald initiative was innovative in several ways. It was an early version of the challenge grant, which drew matching funds from the community. It was a public-private partnership: county school boards had to staff and maintain the buildings. And it included a “sunset” clause that required all funds in the foundation be expended within 25 years of Rosenwald’s death.

Credit: Andrew Feiler

Credit: Andrew Feiler

The last school was built in 1937 near President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Warm Springs retreat. Roosevelt covered a $1,000 shortfall for the project out of his own pocket, and spoke at the school’s opening.

Integration brought an end to the Rosenwald schools, though many continued to serve their communities long after 1954′s Brown v. the Board of Education.

Their impact extends into the present day.

Labor economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago estimate that 40% of the gains realized by African Americans between the two World Wars could be attributed to the Rosenwald schools.

The schools themselves, some tattered, some restored to new uses, stand as an emblem of the drive toward betterment.

“These schools put the student at the forefront of education for southern African American children,” writes Brent Leggs, a preservationist and a scholar of the Rosenwald schools, in an afterword to the book. “The architecture of the schools was a tangible statement of the equality of all children.”

EXHIBIT PREVIEW

“A Better Life For Their Children.” Through Dec. 12. noon-5 p.m. Thursdays, Fridays and Sundays; 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Saturdays. $16. National Center for Civil and Human Rights, 100 Ivan Allan Jr. Blvd., Atlanta. 678-999-8990, civilandhumanrights.org.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured