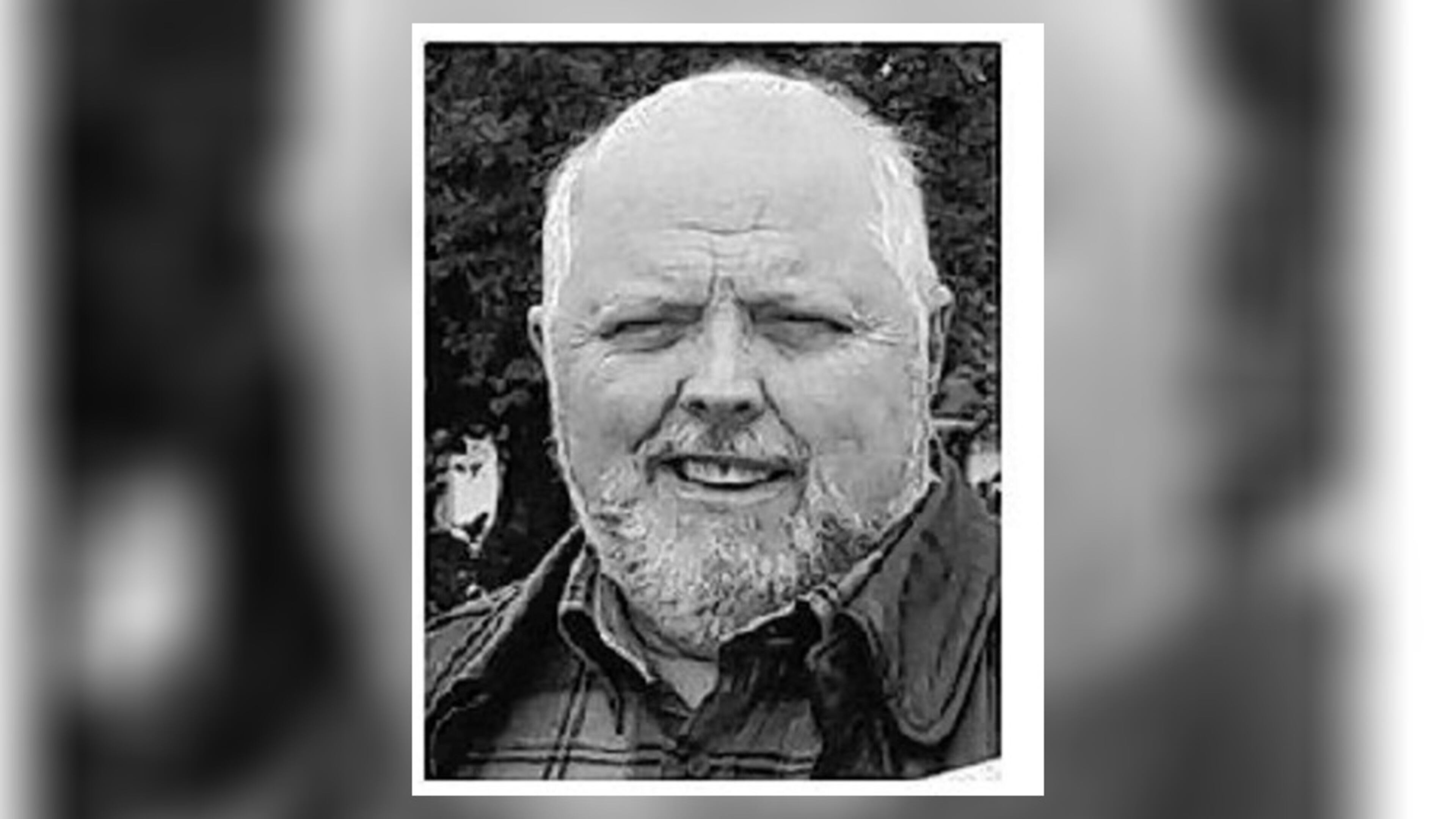

Charles Stone, Olympic bombing investigator, dies

Charles Stone, a career lawman who played a major role in the investigation of the 1996 Centennial Olympic Park bombing, never took the tough-guy approach with suspects.

“Charles did not interview. He did not interrogate,” said Vernon Keenan, former director of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation and Stone’s longtime friend. “He talked to people.”

That technique helped solve cases and produced some unusual results.

“Even some of the felons he sent to prison became friends with him,” Keenan said. “They held no animosity toward him because he was doing his job, and he did it in a low-key, friendly manner.”

Charles Stenius Stone, a retired GBI special agent, author, and devoted family man who approached work and life with humor and optimism, died May 10 after an extended illness. He was 71.

A memorial service was held Monday at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Newnan.

Stone, a native of Aberdeen, Maryland, grew up in Monroe, about 50 miles east of Atlanta. He received his undergraduate degree from the University of West Georgia and his Master of Public Administration degree from the University of Georgia.

Stone spent his career with the GBI, the state’s chief investigative and law enforcement agency, starting in 1973 when he and Keenan became two of the agency’s first hires who were not politically connected, Keenan said.

Stone worked on hundreds of complex cases from murders to timber thefts in his 26 years with the GBI. The Olympic Park bombing by Eric Rudolph was his last and best known.

“Charles played a critical role in representing the GBI and state in the search for Eric Robert Rudolph,” said John Bankhead, the longtime spokesman for the GBI, now retired. “And because of his excellent relationship with local law enforcement, he was one of the first to be notified when Rudolph was captured by authorities in North Carolina.”

Other bombings involving Rudolph were at a gay bar and clinics that provided abortions.

Rudolph eluded capture for years but was arrested rummaging through a dumpster for food outside a rural grocery store in Murphy, N.C., in May 2003. He is serving multiple life sentences for committing four bombings between 1996 and 1998 in Atlanta and Birmingham.

Stone was already working on the GBI’s joint terrorism task force when the bomb went off in Centennial Olympic Park on July 27, 1996, killing one and injuring more than 100.

“After the bombing, he was the first agent assigned full-time to the bombing investigation, and he remained on that investigation until Eric Rudolph was convicted in federal court,” said Keenan, GBI director from 2003 through 2018.

Colleagues and family described Stone as entertaining, humorous, and friendly with a taste for fancy single malt Scotch and a passion for story-telling.

“But underneath that personality, he was a very tenacious criminal investigator,” Keenan said. “He was extremely skillful in collecting information. He was one of the most intelligent people I’ve ever known.”

Dale Russell, a longtime investigative reporter at WAGA Fox 5 Atlanta, said he first met Stone during the bombing investigation. He said Stone was “like the favorite uncle you’ve known all your life.”

“I swear to God I would confess anything to him,” Russell said. “You didn’t think of him as a hard GBI agent, and I think that was the foundation of his success.”

Keenan said Stone was able to develop a rapport with the criminal element. As a result, many agreed to be informants, helping both state and federal law enforcement agents.

In retirement, Stone co-wrote “Hunting for Eric Rudolph” with Henry Schuster, who was an investigative producer at CNN at the time of the Olympic bombing and is now a producer with CBS’s “60 Minutes.”

Stone was candid about the big mistake investigators made in the park bombing case: exposing the name of a suspect too early. Once park security guard Richard Jewell’s name was leaked as the suspect, Jewell went from hero to villain in three days and Eric Rudolph was able to escape. Jewell was later cleared.

“You have to keep your eyes open and not have fixed tunnel vision on one person,” Stone said in a 2013 interview with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “And you don’t release their name unless you have a good, solid reason.”

Stone suffered from kidney problems but a generous former GBI colleague, Mary Anne Jenkins, donated a kidney to him in 2012. The gift allowed him another 10 years of life and the chance to meet and know his grandsons, family said.