Inclusivity and optimism reign at 2019 Atlanta Biennial

A show that may genuinely offer something for everyone, the 2019 Atlanta Biennial “A Thousand Tomorrows” at the Atlanta Contemporary is a uniquely democratic endeavor for artists and audience alike.

“I like the idea that a visitor could come in here and, whoever they are, whatever background they’re from, whatever age they are, they can come in and find someone that looks like them,” says independent curator Phillip March Jones, who mounted the exhibition alongside Atlanta Contemporary curator Daniel Fuller.

“I wanted to represent the South as this dynamic, engaging place that it is,” says Jones, who splits his time between Lexington, Kentucky, and New York City.

Composed of 21 artists from throughout the Southeast, the 2019 Atlanta Biennial is just one in a cycle of hundreds of contemporary art biennials including the Sao Paulo Biennial, the Whitney Biennial and the Venice Biennale that unfold across the globe and bring together artists working in a variety of disciplines. “Biennials are markers of time and place,” says Fuller, who conducted studio visits throughout the region to create the show. The Atlanta Biennial’s distinction within that worldwide biennial phenomenon is its particularly Southern cast.

The Atlanta Biennial has had an on-again off-again rhythm since it was first launched in 1984 by curator Alan Sondheim. During its two-decade-long history, the Atlanta Contemporary’s Biennial included notables such as Kara Walker and Radcliffe Bailey before they achieved their present art world renown. In 2016 the Biennial reappeared again after a nine-year hiatus and this most recent Atlanta Biennial comes after another, smaller gap. It is diverse enough and engaging enough to make one hope the Atlanta Contemporary can return to its regular biennial schedule and continue to include guest curators who enrich and expand its vision.

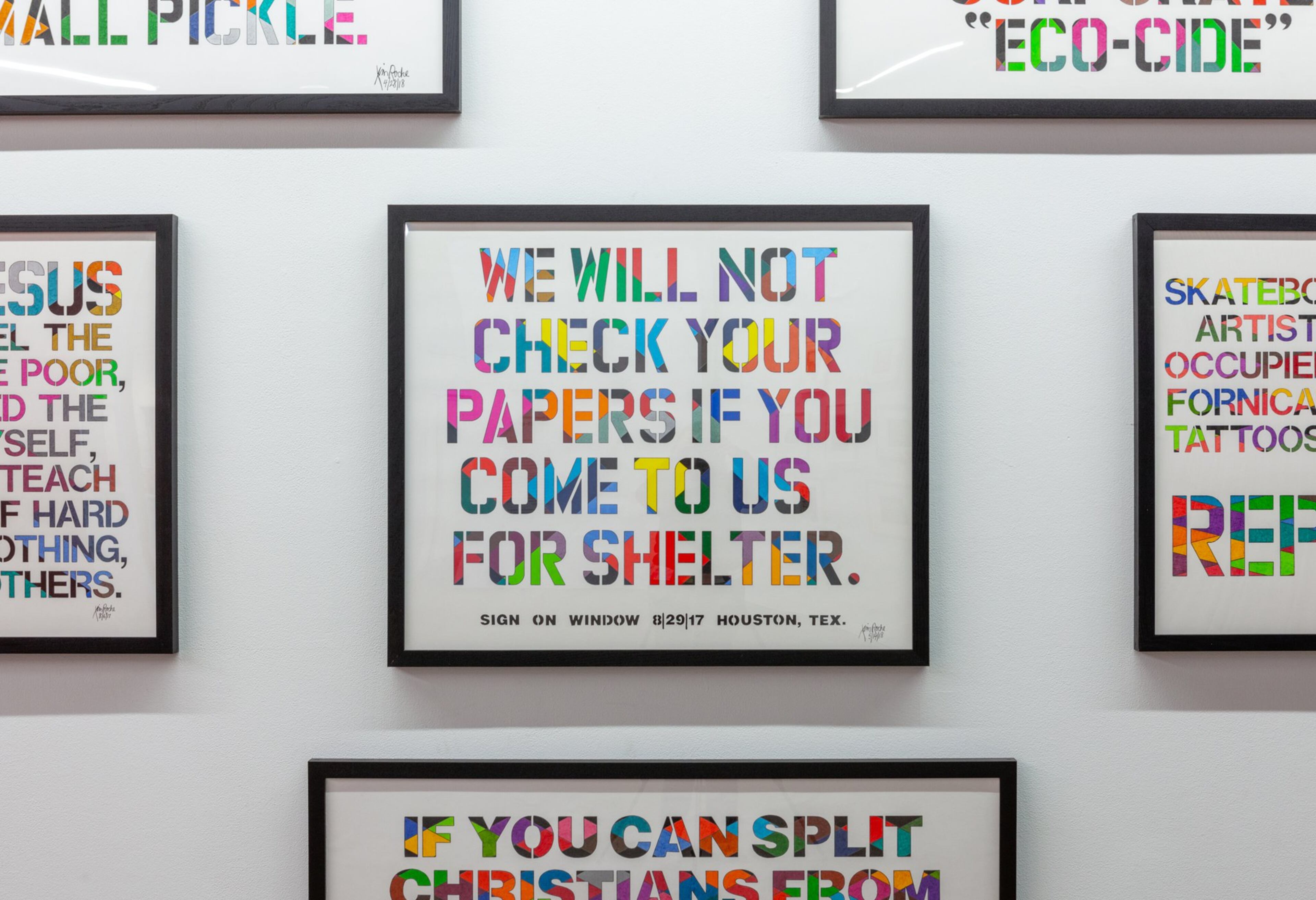

Though Fuller and Jones have tagged this biennial “A Thousand Tomorrows,” it is also an incisive, compelling and often deeply human appraisal of past and present. Themes of history and how we record or rewrite it; contemporary politics; and remembrance make for a uniquely fetching, relatable show.

Along with racial diversity, this year’s Atlanta Biennial marries high art and low art; young and older artists; folk art and conceptual work; art school-birthed and self-taught artists’ works and an even balance of male and female artists. On one end of the spectrum is the work of 64-year-old self-taught artist Melvin Way, whose work is included in the collections of the Smithsonian and the Museum of Modern Art. Way returned to his rural Ruffin County, South Carolina, home to care for his mother after living for decades in a New York City men’s shelter. Way wears his drawings made with ballpoint ink and scraps of paper like talismans on his body “as protective forces,” says Jones. On the other end is 23-year-old recent Rhode Island School of Design graduate Alina Perez, whose warts-and-all self-portraits bring a blunt honesty, vulnerability and authenticity to the portraiture form.

“The 2019 Atlanta Biennial is a testament to the idea that there is much to be gained from exhibiting a truly diverse group of artists,” says Durham-based artist Joy Drury Cox, whose delicate, subtle drawings of the various bureaucratic scripts that define our lives — death certificates, job applications, tax forms — are featured in the show.

“Some group exhibitions in larger art centers, like New York and Los Angeles, tend to lean towards showing the same insular groups of young graduates from high profile MFA programs,” she says.

As Jones says of this Atlanta Biennial, “My philosophy has always been one of radical inclusion. I’m not so interested in the biographical details of someone’s life that might get in the way of them going to school or having the financial resources to pursue a certain path. I try as far as I can to judge an artist by the quality of their work.”

The Atlanta Biennial offers a unique perspective on the South. Former Atlanta Contemporary curator Helena Reckitt used the opportunity of the 2005 Atlanta Biennial to dispel myths about what Southern art looks like.

“I was aware of the dangers of looking for some kind of quintessentially ‘Southern aesthetic,’ which is an overly simplistic idea that fails to recognize how the Southeast is a far from homogeneous place, but home to artists from very wide backgrounds and origins.”

Although many of the artists in the 2019 Atlanta Biennial have more in common with larger contemporary art trends than any regional grounding, several works in the show are informed by the South, steeped in the region’s eccentricity, love of history, interest in found materials and off-kilter humor. Take for instance the “American Music Show.” The lo-fi, loosey-goosey, local cable access show televised from 1981-2005 was produced by a collective of metro Atlanta eccentrics who created weekly episodes featuring musical performances, interviews, comedy skits and spotlighting future legends such as RuPaul and Lady Bunny. Visitors to the Atlanta Biennial can can sit on the mismatched thrift store furniture in a faux-living room installation to watch episodes of a show that often spotlighted Atlanta’s inventive, creative LGBT culture.

Suggesting an iconoclastic blend of the regional and the timeless is the work of artist Jessie Dunahoo (who died in 2018) from St. Helen’s, Kentucky, whose strange, compelling quilts made from stitched-together plastic shopping bags look like the love child of the Gee’s Bend quiltmakers and Mike Kelley. Of Dunahoo’s work Jones says, “I think it’s as important as anything created in the 20th century, artistically.”

Although the exhibition contains a fair amount of political snark, incisive commentary and lampooning of sacred cows, the overall mood of the show, says co-curator Jones, is hopeful.

“We called it ‘A Thousand Tomorrows,’ but it’s very optimistic. All of these artists get up most days and get to work. They’re all driven, dedicated and engaged in what they’re doing. I think that’s the way forward for us as a society.

“People talk about everything right now is so bad … but I still believe as a society we are moving, maybe slowly, but consistently in the right direction.”

That forward looking-perspective is reflected in artist Matthew Shain’s “Post-Monuments” black-and-white photo series documenting the concrete and marble foundations where Confederate memorials, toppled in the 21st century, once stood.

“What’s missing isn’t the Confederate monuments, but all the other history that was obfuscated by that monument,” observes Shain. “We are in the wrenching process of reordering our historical narrative, hopefully along more truthful and inclusive lines.”

That’s what this 2019 Atlanta Biennial offers up, too: An inclusive show featuring artists who are writing a different kind of history, recording the world in alternative terms from what we see in monuments, on mainstream TV, in the media. It’s relatable because it’s human-scale and invites all of us to share in a vision of the future.

EVENT PREVEW

2019 Atlanta Biennial: 'A Thousand Tomorrows.' Through April 7. 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Wednesday and Friday-Saturday; 11 a.m.-8 p.m. Thursday; noon-4 p.m. Sunday. Free. Atlanta Contemporary, 535 Means St., Atlanta. 404-688-1970, atlantacontemporary.org