Psychiatrist’s transcripts among Carson McCullers archives

Among a trove of new Carson McCullers-related archives that includes letters, telegrams, snapshots, tape recordings, birthday cards, menus and a bill for the pink roses that blanketed the author’s coffin, is an astonishing acquisition: a dozen or so transcripts of McCullers’ therapy sessions with her former psychiatrist, Mary Mercer.

"It's really exciting for scholars. There's a lot of new material that nobody's really seen before," said Courtney George, director of Columbus State University's Carson McCullers Center for Writers and Musicians, which is dedicated to preserving the writer's legacy.

The archives – acquired last year from the estates of a psychiatrist and a scholar – make CSU one of the top three destinations for research on the brilliant but tormented Georgia author.

Born in Columbus in 1917, Lula Smith Carson moved to New York after high school to pursue a writing career. She published her first novel, “The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter,” at age 23, winning instant acclaim. She married James Reeves McCullers, divorced, and then wed him again. Despite an encyclopedia of physical ailments, she produced short stories, plays, poems, non-fiction pieces, an unfinished autobiography and a children’s book. Her novels anchored her place in the Southern grotesque genre while resounding with themes of loneliness, separation and unrequited love.

The new archival material at CSU’s Simon Schwob Memorial Library may help answer questions that have long tantalized scholars. Did McCullers have a romantic relationship with her former psychiatrist? What was her relationship with her childhood piano teacher, to whom she formed a deep attachment? What can be learned about the author’s final years, when she was bedridden and unable to write much?

“Most scholars who have done biographical research have been interested in McCullers’s sexuality and the nature of her relationship with Dr. Mary Mercer. I do believe that these new materials might provide scholars with new insight,” said Carlos Dews, a preeminent McCullers scholar who edited “Illumination and Night Glare: The Unfinished Autobiography of Carson McCullers.”

How CSU came to inherit Mercer’s archives is a love story of its own.

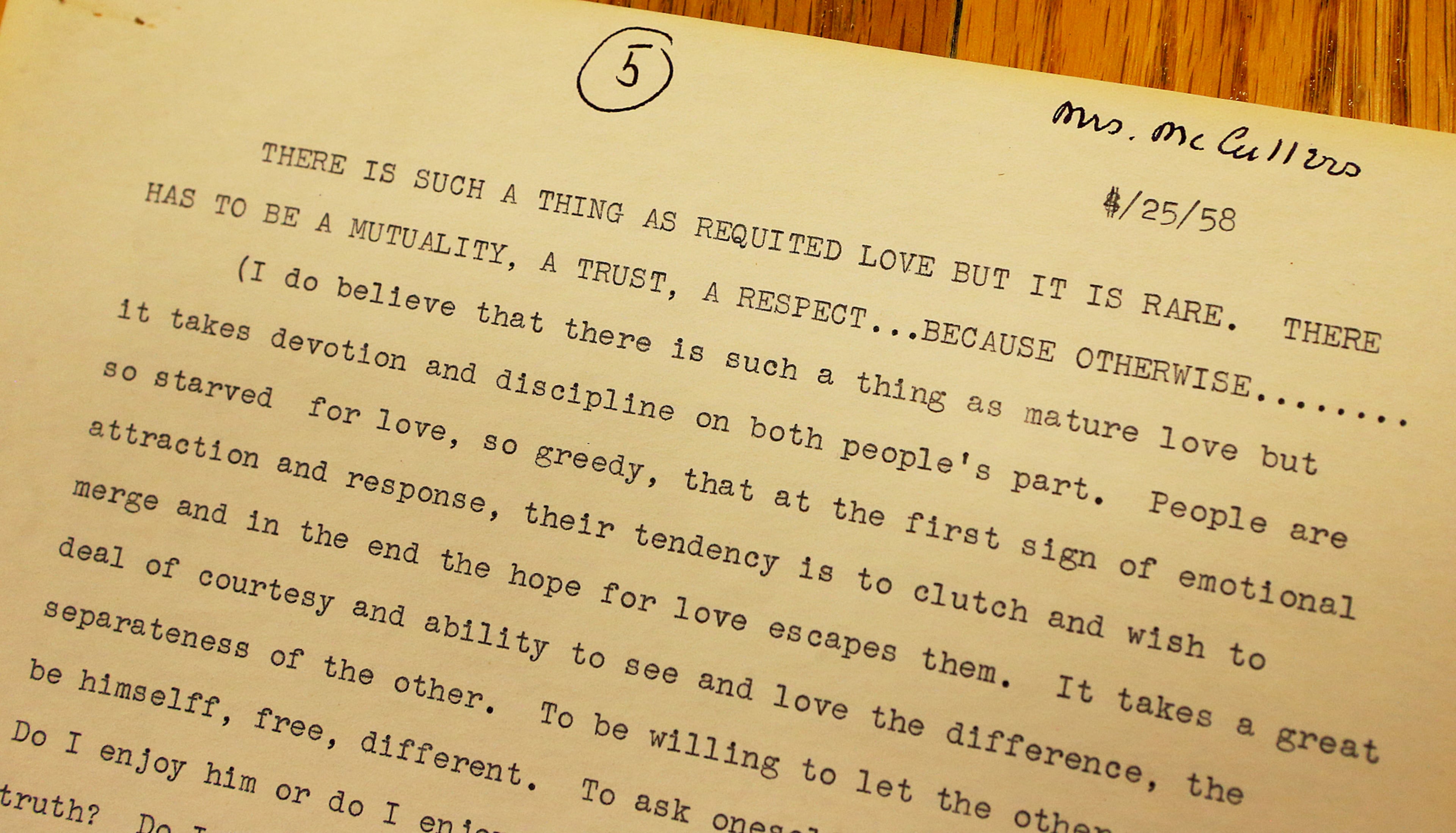

In 1958, suffering depression after her play “The Square Root of Wonderful” had an unsuccessful Broadway run, McCullers sought counseling with Mercer, a child psychiatrist who lived just a few blocks from McCullers’s home in Nyack, New York. Many of the sessions were recorded by a dictation machine. The archives hold the transcripts, which contain McCullers’ and Mercer’s handwritten annotations.

One of the transcripts, dated April 25, 1958, presents McCullers’s concept of love:

“I do believe that there is such a thing as mature love but it takes devotion and discipline on both people’s part. People are so starved for love, so greedy, that at the first sight of emotional attraction and response, their tendency is to clutch and wish to merge and in the end the hope for love escapes them. It takes a great deal of courtesy and ability to see and love the difference, the separateness of the other.”

After severing the doctor-patient relationship, Mercer became McCullers’s greatest ally, serving both as an intimate friend and staunch medical advocate. She helped arrange insurance, home attendants and travel plans, writing detailed instructions on where, for example, McCullers’ cigarette holder and silver bourbon cup should be placed during a visit to John Huston in Ireland.

“I’m convinced they truly loved each other,” said Cathy Fussell, former director of the McCullers Center, who met with Mercer numerous times from 2003–2011.

“It’s been said that, had it not been for Mary Mercer, Carson would not have had those last 10 years of her life,” Fussell added.

McCullers died at age 50 after a brain hemorrhage in 1967, and for the next 44 years, Mercer worked diligently to keep her memory alive. She acquired the writer’s Nyack house, a three-story Victorian that McCullers had subdivided into income-producing apartments at the suggestion of Tennessee Williams. She had the house photographed and detailed notes made about paint brands and colors, repairs and even furniture polish. She rented rooms to artists to recreate a miniature Yaddo, the artist community in Saratoga Springs, New York, where Carson wrote “The Ballad of the Sad Café.”

Mercer also has been a strong supporter of the McCullers Center, which provides cultural and educational programs, and operates the Smith-McCullers House Museum, located in the author’s childhood home, a Craftsman bungalow. Mercer traveled to Columbus for the center’s grand opening in 2003 and, with another donor, endowed a writer fellowship.

When Mercer died in 2013 at age 101, the university inherited about 10,000 pages of McCullers-related material that Mercer had meticulously inventoried and stored in file cabinets in her home.

“We got two complete filing cabinets, shrink-wrapped, exactly as they were in her house,” said David Owings, CSU archivist.

Mercer also gave the university the author’s Nyack home, her art and book collections, artifacts, photographs and signature pieces of her clothing and furniture, as well as $350,000 for curatorial and conservation work.

Visitors to the museum can view McCullers’s liquor cabinet and the white marble table where the author entertained Tennessee Williams, Marilyn Monroe, Arthur Miller, Isak Dinesen, Edward Albee and Julie Harris.

Though currently occupied with artist tenants, the Nyack house will be used for lodging for CSU’s “study-away” programs in the New York City area.

Mercer had inherited one third of McCullers’s estate, with the other shares going to the writer’s brother and sister. The siblings gave McCullers’ papers to the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas in Austin.

By some accounts, Mercer appeared conflicted about breaching the doctor-patient boundary with McCullers.

“Mary was always very careful to say, ‘We severed our professional relationship before we had a personal relationship,’” said Fussell.

Asked whether Mercer ever discussed the ethical considerations of making a former patient’s medical records public, the executor of Mercer’s estate, Joan Mertens, curator of the department of Greek and Roman Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, declined comment.

The Margaret Sullivan papers at CSU, available to the public since April, offer a different set of challenges and opportunities. An early McCullers scholar who died in 2012, Sullivan befriended McCullers, Mercer and Mary Tucker, a Columbus piano teacher who played a pivotal role in McCullers' life. Her archives are notable for the voluminous correspondence from people who knew McCullers.

Sullivan’s niece Nancy Burgin said she turned over “boxes and boxes and boxes of papers and taped interviews” while cleaning out Sullivan’s house.

Using an old-fashioned tape recorder, Sullivan had traveled across Columbus and the nation, interviewing people who knew McCullers, said Burgin. “It was her passion.”

“What’s significant about Sullivan’s collection is that Sullivan and Tucker were writing to one another about McCullers,” said Carmen Skaggs, chair of the CSU English department. “When you’re writing about someone else, you say things you wouldn’t say to that person directly. Mary Mercer and Carson talk about Mary Tucker. Mary Tucker and Margaret Sullivan talk about Carson. We can look at their relationship in a more complete way than we could before.”

Smith-McCullers House Museum. 9 a.m.-noon, 1-5 p.m. Monday-Friday. 24 hours notice required for group tours. $5 suggested donation. 1519 Stark Ave., Columbus. 706-565-4021. www.mccullerscenter.org

Simon Schwob Memorial Library. 9 a.m.-noon, 1-5 p.m. Monday-Friday. 4225 University Ave., Columbus. 706-507-8672. archives.columbusstate.edu