Ode to the Great Migration, Harlem Renaissance

If there ever was a gift that keeps on giving, it is the work of renowned Harlem Renaissance author and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston.

Hurston, who died in 1960 at the age of 69, published her novel "Their Eyes Were Watching God" in 1937. But her prolific literary career crossed over multiple genres. In addition to penning novels, she recorded African-American folklore from the South and wrote essays and short fiction. Fifty-eight years after her death, "Barracoon: The Story of the Last 'Black Cargo,'" was published in 2018. It recounted the life of former slave Oluale Kossula, who was kidnapped from West Africa and brought to Alabama on the last transatlantic slave ship.

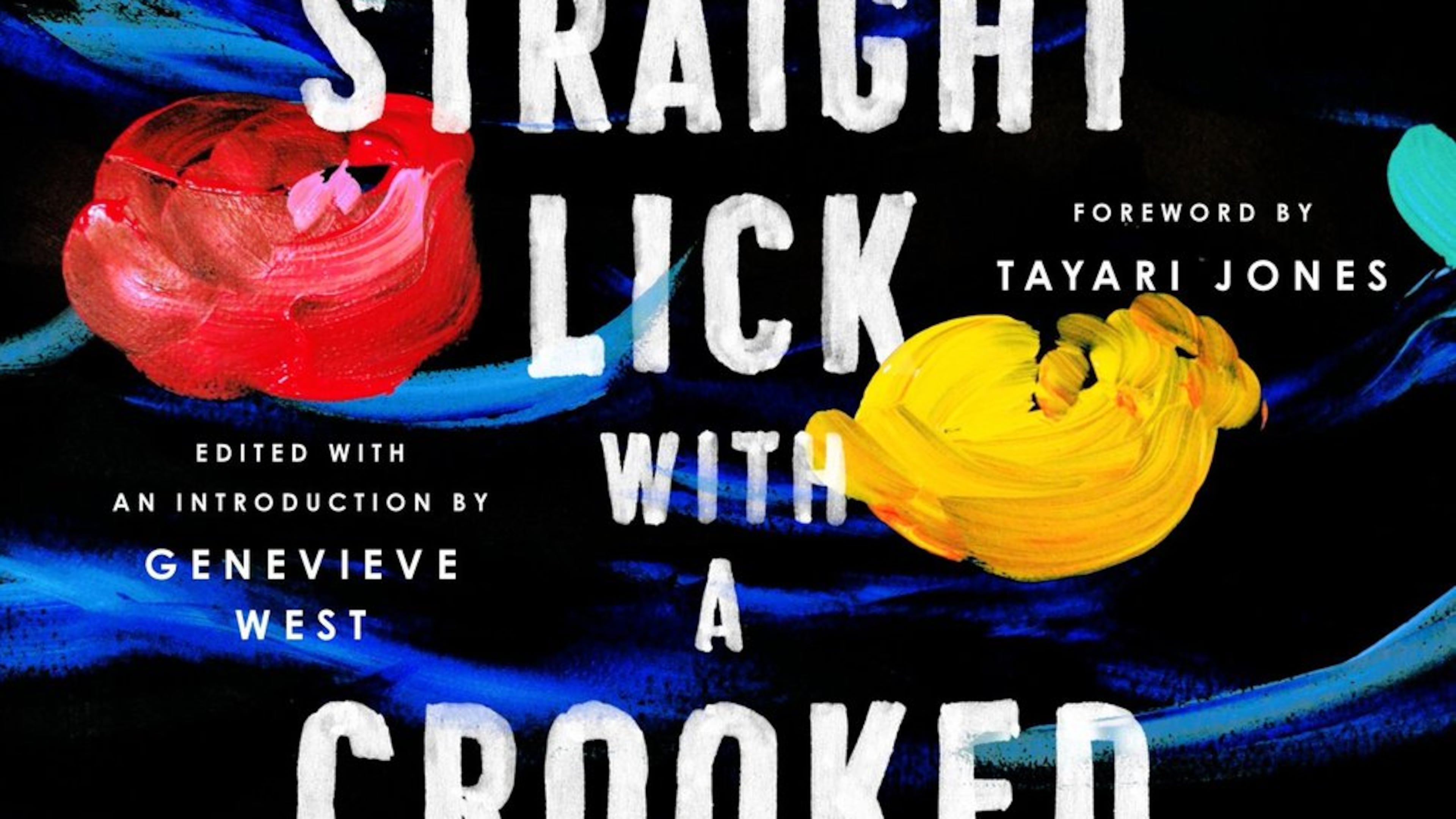

Hurston’s newest posthumous book is the short story collection, “Hitting a Straight Lick with a Crooked Stick.” These 21 vibrant stories, which she wrote between 1921 and 1937, parse toxic masculinity, infidelity, addiction, the male gaze, resistance to gender norms and marriage. The Great Migration, when the segregationist laws of Jim Crow forced millions of black people to migrate north to build new lives, hovers in the background. Eight of the nine “lost” stories that appear in the collection take place at the height of the Harlem Renaissance. They depict the urban energy of the New York City borough where many of the migrants landed. Other stories focus on rural life in Eatonville, Florida, the first incorporated all black city in the U.S. and Hurston’s childhood hometown.

Escape is a dominant theme in “Hitting a Straight Lick,” where characters brimming with optimism daydream of greener, farther away pastures. In “John Redding Goes to Sea,” 10-year-old John views the horizon, where “the sky touches the ground,” as a doorway that leads to an adventure he must embark upon. His mother Matty sees her son’s obsessive desire to travel as a rejection of her. “John, John, mah baby! You wouldn’t kill yo’ po’ ole mama would you?”

Despite his efforts, John remains geographically confined, but he finds other ways as an adult to move away from his family, especially linguistically. He casts off his parents’ idiom (Hurston’s preferred term over “dialect” to describe her characters’ speech). “I’m stagnating here,” he explains plainly. “This indolent atmosphere will stifle every bit of ambition that’s in me.” It’s hard to believe “John Redding” is Hurston’s first published story. It is as perceptive and polished as her later ones.

A far happier fate awaits 8-year-old Iris in “Drenched in Light,” a story that marked Hurston’s first major publication. Iris is an imaginative and precocious child who dances around wearing a red tablecloth while rejecting the femininity her grandmother attempts to foist upon her. Despite the harsh punishment Iris receives for her antics, the resourceful little girl finds a way to forge her own future. One wonders whether John and Iris reflect the restlessness of a young Hurston growing up in Eatonville while longing for New York.

Hurston’s prose is exuberant and playful, but there are dark notes in her stories, too. Revenge is a theme she deftly executes through the use of otherworldly spirits or town folk capable of casting “conjures” or curses. In “Spunk,” cocky Spunk Banks, who isn’t “skeered of nothin’ on God’s green footstool,” struts around Eatonville with Joe Kanty’s wife on his arm. When Joe challenges Spunk to a dual, their confrontation leads to Joe’s death. But Joe returns to exact revenge from beyond the grave.

The radiant “Black Death,” a story that was unpublished in Hurston’s lifetime, also touches on the supernatural. In it, Old Man Morgan, a hoodoo man renowned for his conjures in Eatonville, can kill people without leaving his house or seeing his victim. Mrs. Boger, whose daughter Docia was jilted by Beau Diddely, hires Old Man Morgan to teach Beau a lesson. Beau’s unusual end would come to be known as Morgan’s “masterpiece.”

The sweetest revenge story in “Hitting a Straight Lick” doesn’t involve spirits or magic but a woman named Delia Jones whose husband, Sykes, beats her and subjects her to cruel pranks. The title, “Sweat,” refers to Delia’s backbreaking work of washing white people’s clothes to put food on their table and pay for their home. “Her tears, her sweat, her blood. She had brought love to the union and he had brought a longing after the flesh.”

Fifteen years into their marriage, she puts her foot down. “Delia’s habitual meekness seemed to slip from her shoulders like a blown scarf. She was on her feet; her poor little body, her bare knuckly hands bravely defying the strapping hulk before her.” Hurston pens a deeply satisfying ending reminiscent of the kind of African folktales she collected throughout her career.

A familial love triangle plagues the protagonist in “Under the Bridge.” Fifty-eight-year-old Luke Mimms takes great pride in marrying the “radiating” Vangie, who is about the same age as his adult son, Artie. After a rough beginning, Vangie and Artie become jovial companions. But Luke’s relief at their newfound harmony turns to jealousy over the undeniable romantic chemistry between them. “The bitterness of life struck him afresh. He blamed them. He didn’t. Poor creatures! Designing devils!” Be careful what you wish for is a moral that Hurston artfully weaves throughout the collection.

“Hitting a Straight Lick” may mark one of the last of Hurston’s literary works brought to full-length book form. One hopes, though, that more of her archived words will find their way into a future published volume. Miracles do happen.

FICTION

‘Hitting a Straight Lick with a Crooked Stick’

By Zora Neale Hurston

HarperCollins

304 pages, $25.99