Though art history is more often a story of men surveying the world, American photographer Doris Ulmann bucked that tradition. A wealthy New Yorker with a camera, Ulmann had a diverse array of photographic interests. She would, over the course of a career spanning from 1915 to 1934, photograph faces as illustrious as Albert Einstein and Martha Graham, as a kind of Annie Leibovitz of her era. But Ulmann was also an aesthetic free spirit, delving into documentary photography, pictorialism and even a modernist movement that defied traditional approaches.

The exhibition "Vernacular Modernism: The Photography of Doris Ulmann" at the Georgia Museum of Art is a resurrection of this lesser-known voice in photographic history, and a tribute to an innovator in many regards.

As curator Sarah Kate Gillespie notes, Ulmann was a pioneer on multiple fronts. She was one of the first to undertake portraiture in the rural South; to collaborate with a writer, Julia Peterkin, on a documentary project, “Roll, Jordan, Roll”; and to extensively photograph African-Americans from all walks of life.

Her forays into the South (including Georgia) are especially notable, expressive and clearly enthralled by its landscape and people. Works like “Preparing for Baptism” of an African-American woman standing knee-high in water flanked by two men also dressed in white and framed by lush Southern foliage looks like something from a dream. Her portrait of a young girl with downcast eyes and a dancer’s thoughtful posture in “Little Girl” is incomparably beautiful, and like many of Ulmann’s images, both images capture the exoticism of the landscape, the particularities of regional life and the exquisite poetry of ordinary people.

What “Vernacular Modernism” also illustrates is the radical departure of a world seen through a woman’s eyes, as in a small but incredibly telling selection of works from the 1930s in which Ulmann documents her handsome assistant and lover John Jacob Niles. Shown at the piano, hauling Ulmann’s photography equipment or simply peeking out from beneath a fedora and upturned coat collar, Niles is a sensual muse beneath Ulmann’s gaze, an object of both desire and admiration for his many talents.

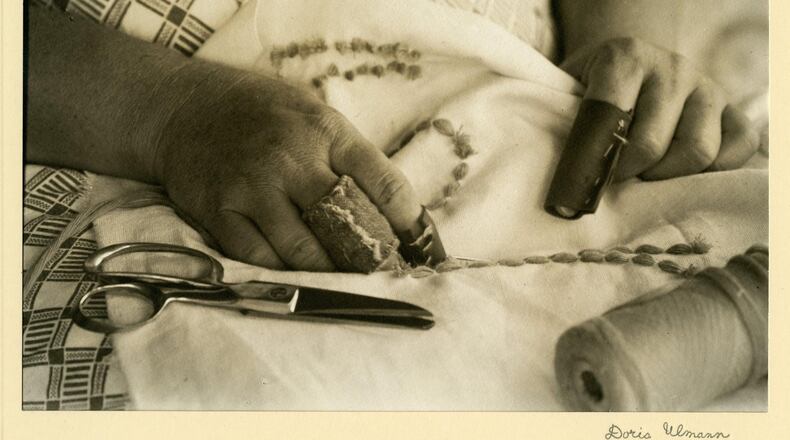

Roaming around the South and Appalachia, Ulmann brought a similarly romantic vantage to a wide swatch of humanity: basket weavers, blacksmiths, furniture makers and vegetable sellers. Labor was an ongoing topic for Ulmann. She showed a clear fascination with how people made their way in the world and brought dignity rather than condescension to their endeavors.

Her use of printing techniques to lend a pictorialist, dreamy, painterly look to her photographs not unlike oil paintings often consigned her to a more traditionalist camp. But it is the argument of “Vernacular Modernism” that Ulmann was far more, as much an innovator and modernist as contemporaries like Charles Sheeler or Edward Steichen who were challenging the conventions of representation.

Objects on loan or gleaned from the Georgia Museum of Art’s own collection are juxtaposed with Ulmann’s photographs to show similar strains and subject matter; the same chain gangs that fascinated Ulmann also entranced painter Margaret Moffat Law in her work “Chain Gang.”

Perhaps the most illustrative, even shocking juxtaposition is Ulmann’s tender, hazy images of a young mother with a chubby baby in “Mrs. Bonnie Logan Hensley and Son John” and a side-by-side portrait of an impoverished family by documentary great Walker Evans. Even today Evans’ image retains its ability to shock: the naked children, the grime, the low-ceiling shack where they live, a sense of exhaustion and despair in their faces. Poverty is vicious, smothering in Evans’ image, but there’s no such angst in Ulmann’s portraits. Even her images of black Southerners, barely out of slavery’s clutches, lend a poetry and dignity to their reality.

Modern or traditional, documentarian or portraitist, there’s no denying Ulmann’s unique eye or the value of this handsome, illuminating exhibition aiming to bring her work to a larger audience.

ART REVIEW

“Vernacular Modernism: The Photography of Doris Ulmann”

Through Nov. 18. 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Fridays, Saturdays; 10 a.m.-9 p.m. Thursdays; 1-5 p.m. Sundays. Free. Georgia Museum of Art, 90 Carlton St., Athens. 706-542-4662, georgiamuseum.org.

Bottom line: An illuminating introduction to a lesser-known female photographer.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured