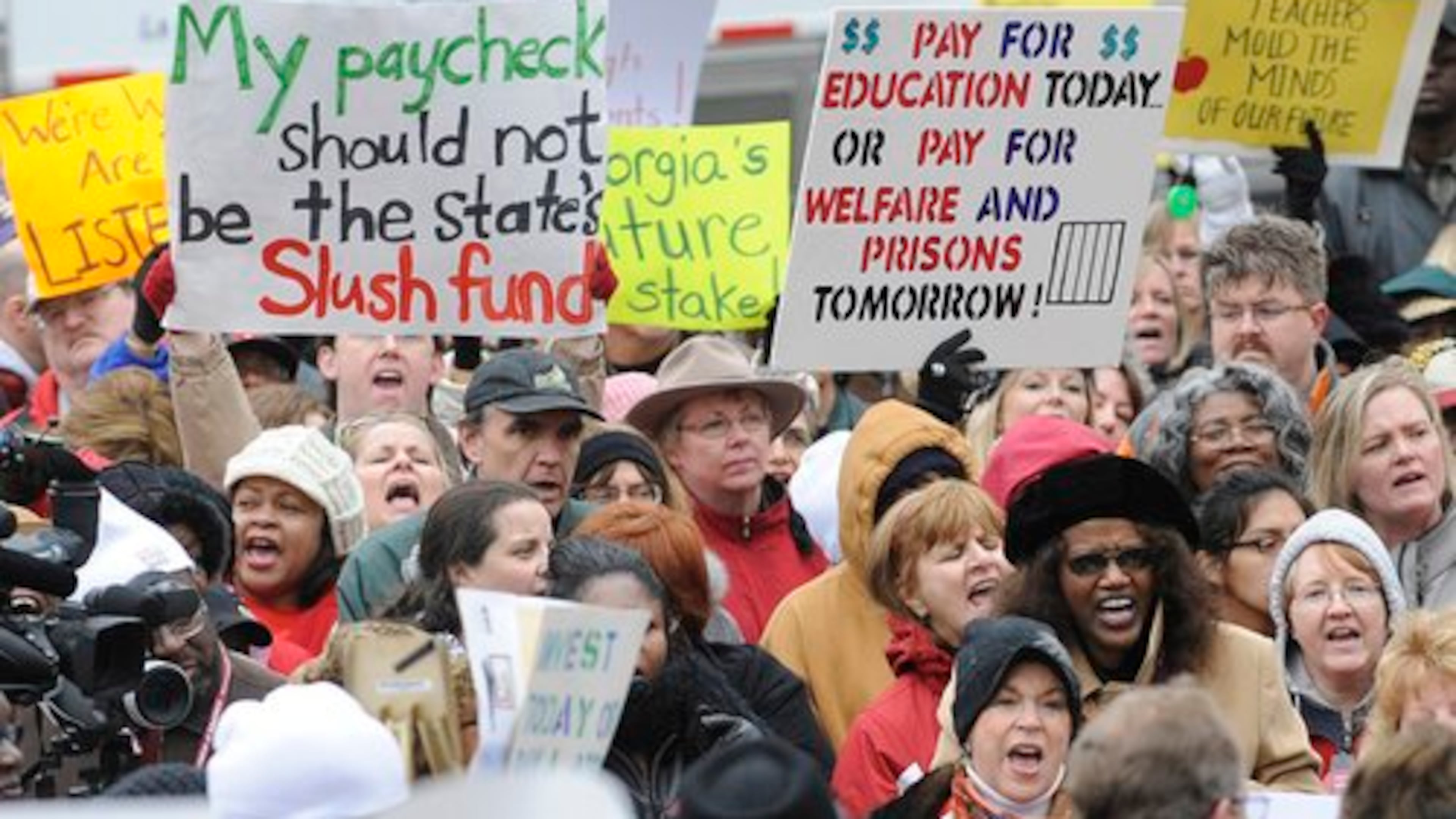

Opinion: Higher expectations for teachers, schools yet same low funding

In this guest column, educator Peter Smagorinsky lists the rising demands on Georgia schools, especially in the aftermath of the pandemic. And he wonders how those lofty goals will be possible with the inadequate funding Georgia now provides its education systems.

Smagorinsky retired from the University of Georgia at the end of 2020. His book, “Learning to Teach English and the Language Arts,” was awarded the 2022 Exemplary Research in Teaching and Teacher Education Award from the American Educational Research Association.

By Peter Smagorinsky

In a recent series of guest columns on the AJC Get Schooled blog, sincere and committed advocates detailed the needs of public schools and the children who attend them. These stakeholders made the case for increased attention to a variety of programs and policies that would improve the quality of schooling in Georgia. AJC columnist Maureen Downey identified the major obstacle to implementing them, “Most involve investing more money in early childhood programs, K-12 schools and higher education.”

And therein lies the rub.

To review from the series: Georgia needs to raise teacher pay, provide funding to support students in poverty, greatly increase the number of school counselors, and invest more in buses and their maintenance. Georgia needs to expand pre-K programs to promote reading, math, and social skills; and to support families with working parents who rely on child care programs to manage their schedules and responsibilities.

Federal COVID-19 relief funding helped, but those funds are running out and the state needs to replace them to sustain the programs they supported. Higher education ought to increase need-based aid for college students. Everyone in a school is underpaid and underappreciated, from teachers to custodians to bus drivers to cafeteria workers and beyond. Continuing to stiff them financially will not entice a generation of replacements to stand in for the many who are looking to work under more respectful and fulfilling conditions.

Students’ emotional and mental health are in crisis, amplified by the pandemic lockdown and politicization of their health. But funding to provide counselors and communities of support is minuscule, especially in light of the gravity of the challenge. After-school programs are being cut, and they provide a key place for students to gather between classes ending and the arrival of parents home from work, with pharmaceuticals and other temptations much farther from reach than they are in a community’s unsupervised locations.

Schools also are continually trying to catch up with technology, which requires routine updating and replacement as systems evolve and require more power and memory. This problem became critical during the shutdown, when online systems were inadequate to the point of forcing many students drive to fast-food restaurants and do homework in their cars on their cellphones. But with virtually everything done online, from attendance and record-keeping to instruction, and with systems and their technologies going obsolete on predictable schedules, it’s a losing battle.

And that’s just the funding part. If politicians and community members continue to politicize and whitewash the curriculum, kids will learn mythology rather than history, and teachers will bail out and do something they feel has more integrity than the profession they love and have been committed to.

These are just some of the challenges facing schools. I’d add building maintenance and cleanliness to the list, a massive investment in schools that have deteriorated over time without upgrades to their structural integrity and sufficient daily custodial care.

There is also a great need for school nurses, who are dwarfed in staffing by policing personnel. Meanwhile, many are calling for increased security, given the recent cases of violence in and around schools, often credited to post-COVID socialization problems. Others take a less punitive approach, calling for restorative justice programs that are labor-intensive and require choices over how to allocate staff time. Neither intervention is free.

Meanwhile, if Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has his way, a public school may be defined as any school getting public money, which in his state now includes private schools that siphon off funds to support the education of the state’s wealthiest families’ children.

And then there are calls for when to start school. Some now say that boys’ later maturation suggests the need for them to start school at a later age; others have promoted a later start to the school day. What to do with those kids for the extra year(s) at home — remember, pre-K programs are being cut from budgets — remains an abstraction. And the question of starting school later needs to acknowledge the critical shortage of bus drivers, not to mention the condition of buses and the complex scheduling required in many large districts to get everyone where they belong on time.

And so, everyone has a great idea for how to improve schools. All of them cost money. And Georgia taxpayers have been loath to support increases for anything, much less schools. The Georgia politicians the taxpayers elect thrive on villainizing schools and teachers while shortchanging their livelihoods and their effects on students.

Yet, the rhetoric is always about world-class education and the importance of being educated, unless you are DeSantis, whose Yale and Harvard degrees nonetheless have led him to conclude that the college experience is virtually meaningless, especially when it comes to learning how to teach, allowing him to hire replacements on the cheap and without attention to their qualifications.

High demands, low funding, indifferent care. Georgia taxpayers, the future is in your hands, and the present is at your fingertips. You are electing the politicians whose votes will determine the degree of investment in kids and their learning, socialization, life trajectories, physical and mental health, and more. My fellow Georgians, the problem is shared by all of us. What are you going to do about it?