I don’t understand the resistance to loosening school dress codes since no one seems to like them -- not the kids subject to them, the parents opposed to their inherent sexism, or the school personnel forced to enforce them.

I recently wrote about a Cobb middle school student’s effort to reform the dress code there. Since then, Sophia Trevino’s campaign in Cobb has drawn national media attention.

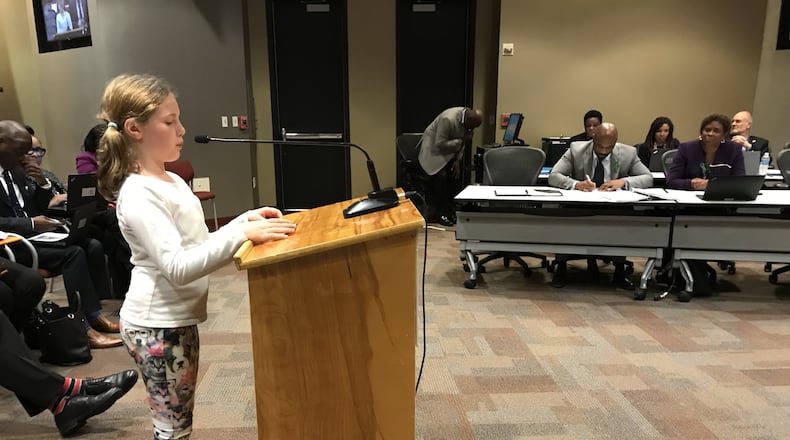

Sophia is one in a long line of dress code warriors. For example, in 2017, two students at Springdale Park Elementary School complained to the Atlanta Public Schools Board of Education about it dress code, which banned “extremely tight” and “distracting” clothing, including leggings. The fifth graders spoke to the board in leggings without causing a distraction and getting their point across. (Their campaign, too, made national news.)

Student Falyn Handley, then 10, told the board: “This is a label applied to girls’ clothing. I do not believe that clothing is a distraction. It is just the reaction that matters. I should not be punished for other people’s behavior. I am not a distraction.”

The APS dress code now does not mention “distracting” attire. It does state: “Clothing, hairstyles, and jewelry must not cause a disruption or constitute a health or safety hazard.”

In this guest column, two local parents who are also therapists explain the damaging nature of dress codes.

By Amy C. Bryant and Janie Mardis

As both mothers and professional mental health therapists, we are increasingly concerned about the tremendous amount of stress children experience, especially as rates of anxiety and depression in adolescents continue to rise. And in the midst of COVID-19 related worry, our ears began to perk up as it became increasingly clear that another issue was contributing more harm than good on mental health: school dress codes.

Dress codes that consider the developmental needs of students can contribute to healthy growth, development, and critical thinking skills. However, many dress codes in use today are too strict, and families continue to report how difficult it is to find clothes that are affordable, aligned with strict dress codes, and kid approved.

Some kids, particularly those who are differently abled or who exhibit aspects of neurodiversity, find “dress-code-acceptable” clothing uncomfortable, restrictive, and distracting. If you’ve ever had an itchy tag or a poor-fitting shirt that made you feel self-conscious, you can relate to this challenge.

Families with few financial means struggled to find clothes that would fit for as long as possible--a challenge when growth spurts can make skirts and shorts “unacceptable” practically overnight.

Girls were measuring (and re-measuring) their clothing out of fear that they might get “dress coded.” Dress codes are unevenly enforced and often target Black, Latina, and female-identified students, so these girls experienced even greater stress.

And make no mistake: adolescents are savvy. They see these disparities in enforcement. Some will object. Others will assume that this is just “the way of the adult world.” And voila. Discriminatory practices are normalized and instilled in the next generation.

What does it say to a 10-year-old when her body is routinely measured and critiqued? When she feels constantly scrutinized, subjected to commentary on her basic “appropriateness,” and asked to bend and twirl (yes, this happened) so that adults can “get a better look”? Are you creeped out yet? Good. Then you are picking up on the problem, too.

And where does the problem actually lie when a 10-year-old is monitored for excessive sexuality in dress? The human brain does not finish developing until one’s mid-20s A 10-year-old is, in every sense of the word, a child. To treat her otherwise has the whiff of sexual predation. And yet, this is what is being asked of educators--whether they feel okay about it or not.

Psychologists have long understood that social exploration, connection with peers, and a deep need to be accepted are foundational to the adolescent developmental stage. As parents, we want our kids to be able to focus on academics, make friends, learn what it means to be responsible members of society, feel empowered, and cultivate respect for the differences and the uniqueness they see in themselves and others. We want them to be happy, but how do we help them with these important developmental tasks when they have no room to explore and express who they are? Children don’t learn by being obedient; they learn by trying things out, discovering what feels right and true for them, and adjusting based on experience.

From this perspective, restrictive dress codes are incompatible with their developmental stage, and often become a source of stress, tears and, most disturbingly, shame. And the research on shame is damning. Shame isolates people and results in a lifetime of poor mental health outcomes that get repeated generation after generation. And given that one in three adolescents will experience an anxiety disorder, we must take our responsibility for these kids’ mental and emotional wellbeing very seriously. After all, tears dry, but internalized shame tends to persist.

An argument often made in support of strict dress codes is that girls’ bodies, if not properly covered, are a distraction to boys and result in (a) poorer learning outcomes for boys; and (b) unsafe circumstances for girls. Rather than asking kids to cover their bodies (and sending a message about their bodies’ innate shamefulness), we can teach them that sexual urges are normal, and that they can choose how to respond to thoughts and impulses. We can teach real life skills of self-regulation so they can observe and “surf” impulses that might otherwise result in distraction, unsafe behavior, or sexually hostile circumstances. And a secondary benefit would be a safer and more peaceful world that stops asking, “Well, what was she wearing?”

Children deserve to learn they have agency over their own bodies, control over how they behave, and the same regard for their humanity that adults (hopefully) afford other adults. Because being a kid doesn’t make you less human, right? We all deserve respect and dignity.

A dress code that promotes healthy growth, development, and critical thinking skills considers equitable access to education without reinforcing gender stereotypes or the marginalization of any student based on race, gender, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, household income, gender identity, or cultural observance. There are several dress codes currently in use that we can adopt or use as guidance for revised dress codes, such as the one adopted by the Toronto School Board in 2019 and the Oregon NOW model adopted in 2016.

It’s time for change. We propose the following:

We can create a school climate that rejects homogeneity and supports mental health by respectfully recognizing, talking about, and accepting people’s differences. Schools are meant to educate our children; considering their mental health and developmental needs is key to their education.

We can fund and implement programs that teach children how to regulate their bodies and develop a sense of agency around the relationship between their impulses and actions. After all, sexual harassment is a problem to be solved by perpetrators--not survivors.

And while we’re waiting for schools to catch up with science, we can support our children’s decisions to break the dress code and get into what the late American statesman and civil rights leader, John Lewis, called “good trouble.” After all, the future is theirs. As adults, we must respect their rights by supporting them in forging a more kind, just, and morally courageous world.

The authors of this guest column, Amy C. Bryant and Janie Mardis, are both parents and therapists in metro Atlanta.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured