Like a hiker tossing away unneeded items on the trail, the Atlanta economy has been shedding burdens and gradually picking up the pace.

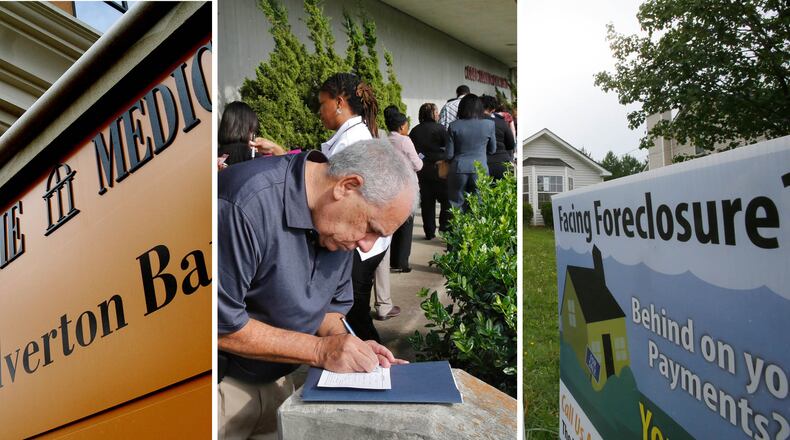

For Atlanta, the load has been mainly the result of a massive housing bust: depressed prices, underwater mortgages and a wobbly job market – a set of weights that are growing lighter as the economy keeps chugging along. Not that we are back again on higher ground – not yet.

For starters, Atlanta is still more than 100,000 jobs shy of its pre-recession peak.One major reason is the lack of jobs in construction and various real estate fields, from architects to closing attorneys. That has forced many people into lower-paying jobs or kept them on the sidelines looking. Or they have given up on the search entirely.

And home prices in many areas have been rising – although in many places they are still far below their pre-bust peaks.

That keeps many homeowners “underwater,” that is, owing more on their mortgages than their house is worth. That may prevent those homeowners from moving. It keeps others from refinancing their mortgage as a way to pay bills or make purchases. And since fewer people can buy a home, the housing market is weaker and there are fewer jobs created.

Metro Atlanta’s home-ownership rate is 60 percent, 55th highest of the nation’s largest 75 metro areas, according to the Census Bureau.

Meanwhile, delinquencies and foreclosures are way down – a good sign. But the financial health of metro Atlanta households is still shaky, according to an analysis by Atlanta-based Equifax.

The number of delinquencies has fallen back toward pre-recession levels. But the lenders – the banks, mortgage firms and credit card companies – are a lot more selective about whom they owe money to than they were in 2006.

Sub-prime borrowers – that is, people with tainted credit and a high “risk profile” – were given loans in large numbers, helping to fuel the housing boom and bust.

“It seems that we are doing a lot better, but the risk profile has changed a lot in Atlanta and around the country,” said Dennis Carlson, deputy chief economist at Columbus-based Equifax.

“If you just look at the broad delinquency rate, it has come back down,” Carlson said. “But there are a lot fewer sub-prime originations and sub-prime cardholders today.”

Using data for mortgages, auto loans and credit cards, Carlson calculated an index for metro Atlanta that shows the region’s debt health improving, but still roughly at 64 percent of the level it was in early 2006. That means that loans to borrowers are much more likely to be delinquent than they were to borrowers who had the same credit rating in 2006.

The number of delinquencies and foreclosures has dropped dramatically, but that is mainly because lenders are so much more selective about whom they lend to, Carlson said.

And even among those with good credit, there is often a greater danger of losing a job and a smaller cushion of savings to fall back on. But having a job is not guarantee that a consumer can handle debts. Many people with steady jobs saw years of stagnant wages, although there has been some improvement recently.

All of that matters for the big picture, since the economy depends on consumers.

They account for slightly more than two-thirds of spending, so when they are footloose and free-spirited, the economy can speed down the trail. When they are weighted down or hobbled, the economy limps along – or slides backwards.

That is one reason that four successive months of a rising unemployment rate in Georgia are troubling. If it because of unexpected seasonal effects or a statistical glitch that will eventually be corrected, that probably means the economy is striding along nicely.

But if those numbers are right, the pace of growth could be slowing as Atlanta suddenly finds itself dragging along a bit more weight.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured