When Chicago O’Hare International Airport held a series of hearings on noise and other issues, more than 2,200 people showed up.

At other airports from Florida to California, hundreds of angry residents show up at meetings to voice concerns about noise, and some are filing lawsuits.

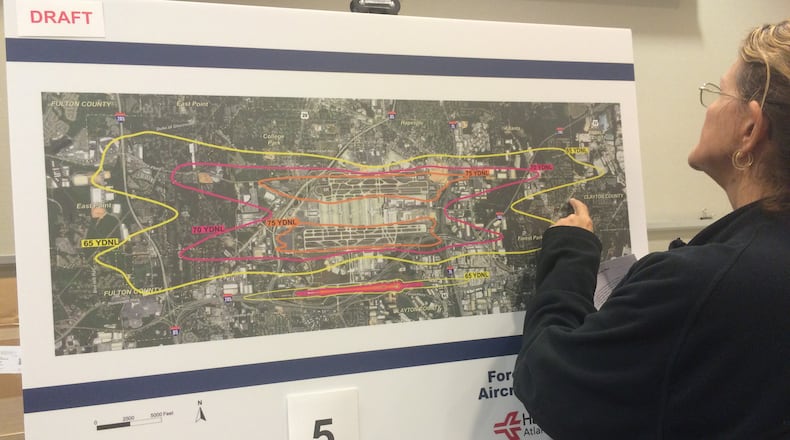

But at the world's busiest airport, no public meetings were held when the FAA changed its flight paths through its Atlanta Metroplex program. And a recent meeting on changes to airport-noise exposure maps drew a total of 11 residents.

For Atlanta, that's not unusual. At Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport, public meetings on airport noise or expansion often draw relatively thin crowds and little interest.

Even elsewhere in metro Atlanta, around smaller airports, resident groups are more vocal.

Residents around Hartsfield-Jackson say people have lost hope that speaking up will make any difference.

A sense of helplessness

“These people have been fighting this fight for years. And they’ve been made promises that have not come through,” said East Point city councilmember Nanette Saucier. “When someone continues to tell you, ‘if you sign a petition, this is going to help alleviate the noise,’ and the noise is gradually getting worse, they’ve pretty much given up. They’re at a level of disgust.”

And, while some flight paths in California or Florida cross wealthy areas, residents around Atlanta’s airport are poorer than average.

While metro Atlanta's median household income is $57,792, it's only $38,305 in the "aerotropolis" area. Many of the homes closest to the airport flight paths are low-rent apartments.

“If you look at the average median income of my city, we don’t have a lot of wealthy people, and I am being their advocate,” Saucier said. “I’m not going to waste people’s money running to sue if I don’t think it’s going to have a positive result … Who’s going to benefit but the attorneys?”

Brenda Adams, a Forest Park resident for 43 years, said, “Those of us who have lived here a long time have come to realize the futility (of complaining about airport noise). It’s like we’ve surrendered.” Adams said the area has “turned into mostly rental property.”

Elleen Yancey of East Point, one of the 11 people at an Oct. 12 airport-noise public information workshop, said in her neighborhood, “We have stopped talking outside because we can’t hear each other.”

She said she submitted so many noise complaints from the late 1990s to early 2005, “I got to know the person who answered the phone” to take the complaints. But she stopped after that service ended. “I guess we annoyed the hell out of them,” she said.

Today, Hartsfield-Jackson takes noise complaints through an online form or voicemail.

Hartsfield-Jackson spokesman Andrew Gobeil said: “We take seriously our desire to be a good neighbor to our nearby communities. The lines of communication, whether through public hearings, correspondence with local officials, or meetings with Airport leaders, are always open.”

Saucier said she is pushing to change federal law so residents can get more noise insulation installed. Currently, homes that were were insulated once before, even decades ago. don’t qualify.

“I personally have been working on this for about ten years, through various organizations that have eventually dissolved — because it’s a hard fight,” she said. “You’re dealing with the busiest airport in the world, and when it comes to resources they have a lot more than a lot of these municipalities that are negatively impacted by the airplane noise.”

East Point residents this month passed a referendum calling on Congress for new noise-exposure regulations and funding for new noise insulation, echoing a measure College Park residents voted for last year.

Atlanta as outlier

Public meetings were not required in 2012 when Atlanta’s flight paths were amended, according to an FAA spokesperson. Since then, the agency “has developed a more robust community involvement program.”

That has led to hundreds of people at meetings and thousands of comments on airport noise — inclulding 4,095 in response to the modified flight patterns in the Southern California Metroplex, which includes Los Angeles International and several other airports.

The Phoenix Metroplex project was suspended after the city sued the FAA over its flight path changes.

Flight path changes in Atlanta have been more subtle than in other areas, and other metropolitan areas around airports are more heavily populated. But community activism about Atlanta’s airport noise is still unusually low.

Maybe that’s because “there isn’t a group of rich people living around it,” speculated Orange County, Calif.-based airport and aviation attorney Barbara Lichman, who has represented cities in suits over airport noise.“I think that it’s linked to the ability to fund it.

“Typically when there are rich people living around the airport, much more resistance occurs,” Lichman said. “People in California are perhaps a little more proactive in this regard, a little more combative … The FAA is being sued willy-nilly,” she said. Elsewhere, “I think it just a feeling of helplessness for certain people.”

John Kane, chairman of Chicago community group Fair Allocation in Runways, put it more starkly: “It’s probably better to build an airport and expand an airport in a poor area, because poor people tend to not fight back. They tend to not have the time and resources to fight back.”

Kane said O’Hare is surrounded by middle-class and working-class communities, and his organization has 5,000 members.

“The most tragic story is the people who have worked their tails off, have actually paid off their mortgages, now are elderly and now have to listen to these planes, breathe this air and watch their houses deteriorate,” Kane said. “There’s not political will to change this. The only recourse we have right now is legal.”

“A really good relationship”

Around Hartsfield-Jackson, some local officials say they are taking a more cooperative approach with the airport that dominates the region. They are also working together to attract businesses and residents to grow the “aerotropolis.”

Council members in East Point and College Park push for solutions to the noise problem, but they have no direct control over Hartsfield-Jackson, which is owned and operated by the city of Atlanta.

“I don’t want to be an enemy of the airport,” Saucier said. “I don’t want to be a bully. I think people should be able to work together in government.” Instead, she said, changing laws on who qualifies for noise insulation would help people who live around airports nationwide.

College Park city councilmember Ambrose Clay, who pushed for the airport-noise referendum, said he has negotiated changes in flight paths and his city’s relationship with the airport and FAA is good. “We at one time were considering a lawsuit, but we work with them and we’ve gotten things optimized as best we can.

“I’m working to change the national noise standards, so ultimately we can get more insulation for people. But outside of that, there’s not much we can do.”

Clay and Saucier both work with the National Association to Insure a Sound Controlled Environment, or N.O.I.S.E., a coalition of local elected officials working to reduce the impact of aviation noise on communities.

“There has been plenty of advocacy on behalf of the residents to the airport and to the city,” said N.O.I.S.E. national coordinator Emily Tranter. She noted, however, that San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago and other communities around major airports have roundtables run by airports to discuss noise issues, or noise oversight committees, while Hartsfield-Jackson does not.

Hartsfield-Jackson’s biggest changes are yet to come. Its $6 billion modernization and expansion includes plans for a sixth runway in the 2023-2034 time frame.

More people showed up nearly a decade ago when the airport was planning to extend a runway, and airport noise issues have drawn bigger crowds to public meetings in the past.

It’s yet to be seen what community reaction that next expansion will generate.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured