The last men summoned by the draft during the Vietnam War reported for duty in June 1973, the same month I turned 18.

And so I was spared the moral quandary of whether to go or not to go. Not that I would have had a choice. The subdivisions blooming along Old National Highway back then were white bastions of blue-collar workers, and my family had no connections to speak of.

The more connections one had, the more choices were available. We’re not talking Canada, but college deferments and friendly doctors who could issue convenient diagnoses. And military service that did not lead to the humid jungles of Indochina.

The class advantages that allowed one to escape the hazards of Vietnam have served as fodder in campaign debates for better than 40 years, most notably during the 2000 presidential campaign of George W. Bush, who completed his military obligations via the Texas Air National Guard.

But these easy berths of the ’60s and ‘70s have rarely been a topic of conversation on the staid floor of the U.S. Senate. Monday was an exception. It was the only way Johnny Isakson could properly explain the debt we owe John McCain.

“I joined the National Guard, of which I’m very proud — I’m still a Guardsman to this day,” Isakson said at the front end of a 10-minute speech. “But it also gave me a chance to serve my country in a way that would not put me in as much risk to go to Vietnam as it would if I was drafted.”

That many young men were able to avoid Vietnam was no secret, then or now. “The ones that could, know it. And the ones that couldn’t, know it,” the senator said.

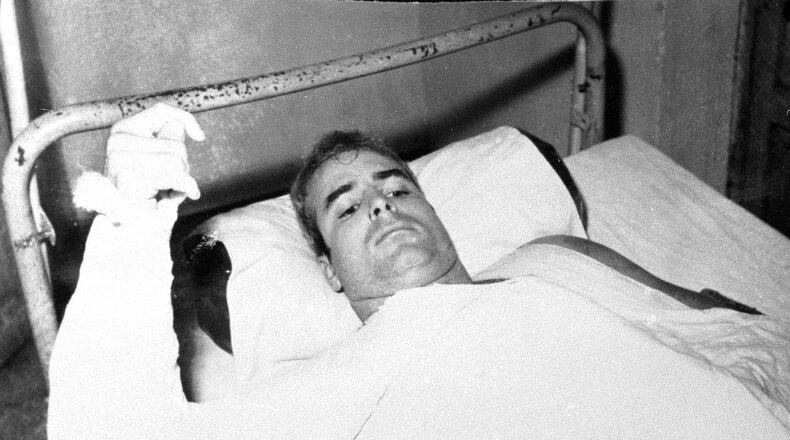

McCain wasn’t special because he couldn’t avoid Vietnam, but because he didn’t.

“I want to elevate John. John was better than me, and I know it. John was the best of my generation,” Isakson said, gathering steam. “Anybody who in any way tarnishes the reputation of John McCain deserves a whipping. Because most of the ones who would do the wrong thing about John McCain, didn’t have the guts to do the right thing when it was their turn. We need to remember that.”

That last fusillade from Isakson was directed at a Donald Trump who, as a candidate, wasn’t sure whether a man who survived five cruel years in a Vietnamese prison should be called a hero. A Donald Trump who, as president, had to be persuaded to lower the U.S. flag above his White House in McCain’s honor.

Never mind that Trump has told reporters that bone spurs kept him away from military duty as a young man.

But Trump wasn’t his only target. Isakson’s remarks were an extraordinary confession aimed at his entire Vietnam generation.

They were an attempt to explain that the political support generated by McCain wasn’t just a matter of enthusiasm, but of contrition. Behind the admiration that spurred two unsuccessful presidential runs was an acknowledgement that McCain had sipped from a cup that others, including many Senate colleagues, had declined.

Isakson’s speech cut to the heart of McCain’s national appeal, but also to the Arizona senator’s lack of traction in Georgia over the years.

The ex-POW was elected to the U.S. House in 1982, and the U.S. Senate in 1986. McCain’s rise coincided with that of a social conservative movement within the GOP that sought to become the party’s moral compass.

But a graduate degree earned at the Hanoi Hilton came with its own moral compass — and authority. Throughout his Washington career, McCain was often at odds with religious conservatives and those pushing the GOP in an ever more ideological direction.

McCain finished second in Georgia’s 2000 and 2008 presidential primaries, losing first to George W. Bush, then to Mike Huckabee. The antipathy of social conservatives was a problem each time.

As a result, McCain’s greatest impact on Georgia politics was indirect, but each episode had roots in the same tension.

In 2002, U.S. Sen. Max Cleland’s bid for re-election was challenged by Republican Saxby Chambliss, who had avoided military service during the Vietnam era with a medical deferment. A GOP-backed TV ad accused the Democrat of voting against President George W. Bush on matters of domestic security — but also showed photos of the terrorist author of 9/11 and the Iraqi strongman whom Bush had targeted for punishment.

McCain and Senate colleague Chuck Hagel of Nebraska, both Republicans, expressed outrage. “I’d never seen anything like that ad. Putting pictures of Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden next to the picture of a man who left three limbs on the battlefield — it’s worse than disgraceful. It’s reprehensible,” McCain said.

Chambliss won, nonetheless. And McCain proved that even moral compasses can swing when magnetic forces shift. He did not blink when Chambliss endorsed him ahead of Georgia’s 2008 presidential primary, as did Isakson. McCain won 32 percent of the vote. Huckabee came in first with 34 percent.

That particular Georgia contest had probably been lost by McCain three years earlier. In 2005, Ralph Reed, the wunderkind of the Religious Right who had served as the organizational talent behind the national Christian Coalition, decided to run for lieutenant governor.

At the same time, McCain, as chairman of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee, embarked on an investigation into ties between Jack Abramoff, a Washington super-lobbyist, and Indian tribes seeking to protect their casinos from competitors.

McCain’s committee exposed Reed as a close associate of Abramoff who accepted money, indirectly, from those Indian casinos. His job had been to rally anti-gambling forces against attempts in various states to expand gaming.

Reed lost the 2006 primary to Casey Cagle, 56 to 44 percent.

So it was ironic that on Monday, that same day that Trump dithered over lowering the U.S. flag, the White House social schedule called for a meeting of John McCain’s most implacable foes. The president hosted a dinner celebrating the evangelical Christian leaders who made his 2016 election possible, and have held the GOP base together ever since.

“We very much appreciate everything that Senator McCain has done for our country,” Trump finally admitted to those gathered, Ralph Reed among them.

But Reed has always had solid political instincts, which this week extended to the man who had helped keep him out of elected office. Two days earlier, understanding that there could be no debate, Reed had pushed out a Twitter message minutes after McCain’s death became public: “RIP, @SenJohnMcCain. He was a patriot, a son & grandson of Admirals, a decorated Navy combat pilot, and an outstanding public servant.”

About the Author

The Latest

Featured