With significant support from Georgia Republicans, Congress may be on the verge of passing a bipartisan bill that would represent one of the biggest changes to U.S. immigration law in more than a decade.

Lawmakers have tackled the radioactive topic without a single public hearing and little floor debate, which helps explain why it’s gotten this far.

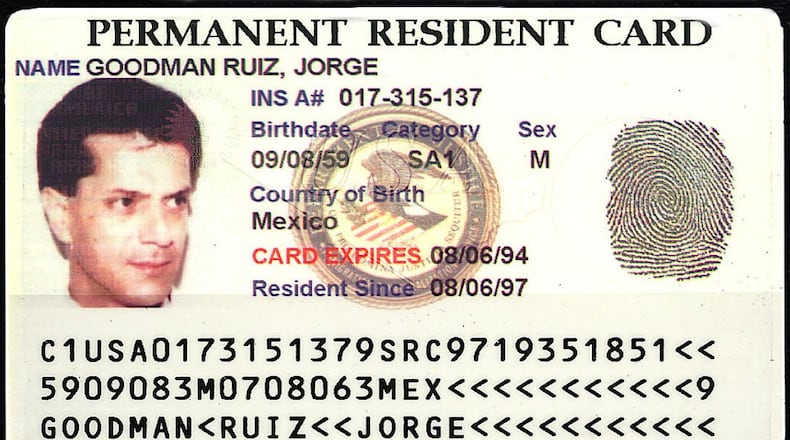

The measure pits the nation’s tech industry against virtually all other enterprises starved for professional talent from abroad. And critics say it would give immigrants from India a decade-long monopoly on all green cards — the permits that allow foreign nationals to live and work in the U.S. on a permanent basis.

Green cards are a virtual necessity for eventual citizenship.

“This bill is not comprehensive immigration reform. It’s not anything close to that. And that is, in fact, why this bill is something we can get done right now,” U.S. Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, the lead sponsor of the bill in that chamber, said in a Thursday floor speech – one of the few times the debate has surfaced in a public manner.

Lee’s legislative partner is U.S. Sen. Kamala Harris, D-Calif., whose mother was an Indian immigrant. Another Democratic presidential candidate, Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota, has added her signature to the bill as well.

Stripped of poison pills, a version passed the House in July on a 365-65 vote, with the support of every Georgia Democrat, and four of nine Georgia Republicans: Austin Scott of Tifton, Jody Hice of Monroe, Tom Graves of Ranger and Rob Woodall of Lawrenceville.

In the Senate, Lee’s version was briefly blocked by David Perdue, R-Ga., who in the past has offered legislation to cut legal immigration into the U.S. by half.

But the senator lifted his hold – and has agreed to support the measure — after winning protections sought by the Georgia Hospital Association, whose members are in the midst of a nursing shortage projected to worsen in the next 10 years.

Charles Kuck, an Atlanta immigration lawyer, brought this topic to my attention last week, when we were on the set of GPB's "Political Rewind."

For decades, immigration into the United States had been restricted largely to western Europeans. Then in 1965, in an effort to diversify the process, Congress passed legislation that restricted immigrants from each individual country to no more than 7% of the overall number of visas allotted in any given year, Kuck said.

At the outset, this change affected immigrants from Mexico, but few others. Then came the national Y2K crisis, a panic over American computer software that failed to allow for computations beyond Dec. 31, 1999.

Tech companies began importing programmers from India, a country that had begun to put a heavy university emphasis on technology.

“In 1999, India didn’t have a backlog on green cards,” Kuck said. “In the last fiscal year, India received 78 percent of the available work visas, the H-1B, and now have about 250,000 people in line for a green card. Plus another 280,000 family members.”

That makes more than half a million Indian immigrants who are in the U.S., standing in line.

Seven percent of 140,000 green cards handed out each year to workers (and their families) amounts to 9,800. So as long as the Indian line doesn’t get any longer, it could be erased in 54 years.

Given that kind of math, Indian-American groups have been lobbying on this issue for the last decade. Mike Lee, the Republican senator from Utah, says he’s been seeking a solution for the last nine years. Why him?

“Utah has become the Silicon Slopes. Once it gets too expensive in California to work, you go to Utah. All the major tech companies that support this bill basically depend on labor from India,” Kuck said.

Since 2007, when an effort at immigration reform blew up in the faces of Senate negotiators – including Saxby Chambliss and Johnny Isakson of Georgia, the topic has been an electrified third rail among Republicans. A 2013 effort was likewise doomed.

This time, negotiators have greatly narrowed their ambitions – and have kept the legislation largely out of public view. In the House, a two-thirds majority allowed the measure to escape without committee hearings or a floor debate.

In the Senate, Lee is seeking to place the measure on the chamber’s unanimous consent calendar, which again would allow the legislation an exceedingly low profile.

Lee’s measure would remove the per-country cap. Green card applicants would be processed on a first-come, first-served basis. And that would put Indian immigrants at the front of the line – while those from other countries would have to take their turn at a wait that could last a decade or more.

“It’s a bill that pits immigrants against immigrants for the scraps from the table,” said Kuck, the immigration attorney.

But the legislation also could pit industry against industry. In the South, that’s health care. The region already has the highest turnover for registered nurses – 16.8% a year. Seven states are projected to have an absolute shortage of nurses by 2030. Georgia is one. South Carolina is another.

Recruiting in other countries, such as the Philippines and Canada, is already taking place. Which is why the Georgia Hospital Association sought David Perdue’s intervention.

Earl Rogers, president and CEO of the organization, said an amendment now attached “will guarantee a minimum of 4,400 qualified nurses per year for the next seven years.

“Without Senator Perdue’s intervention, this number would have been closer to 2,000,” Rogers said.

On Thursday, in his attempt to push his bill through the Senate without any objection, Lee claimed the moral high road. Whatever its original intention, the current system “results in severe de facto discrimination on the basis of country of origin,” he said.

“The German might wait 12 months, while the Indian applicant might wait a decade or more,” Lee said.

The one public opponent of his measure, who could kill the bill’s fast-track status, is U.S. Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill. “In 10 years, there will still be 165,000 people of Indian descent waiting in line, and the rest of the world will still be excluded,” he said in reply to Lee’s pitch.

Durbin is all for removing the per-country cap. But he would also increase the annual number of green cards issued to immigrants – and would make it easier for their family members to become permanent residents, too. But that, Lee said, would amount to a poison pill that Republicans could not accept.

And so the fight over this small but important immigration bill will continue. In the meantime, it helps explain the recent increase in political engagement by Indian-Americans – on the national stage and here in Georgia. Primarily on the Republican side.

Only last month, President Donald Trump met Narendra Modi, prime minister of India, before a raucous crowd of 50,000 in Houston.

During last year’s gubernatorial contest, several Indian-American groups banded together to host a September fundraiser for Republican Brian Kemp.

One of the organizers was Chandra “CB” Yadav, who grew up near New Delhi, India, and now runs a number of restaurants, hotels and grocery stores out of Woodbine, Ga.

Yadav is now a member of the governor’s Georgia First Commission, a panel intended to review regulations and procedures that may impede small businesses in the state.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured