In death, a last good deed from Muhammad Ali

To wish someone dead is bad manners and worse karma. But given that we all owe the Almighty a death, it can be said that some exits are more providential than others.

All of which is prelude to this thought: With his death at age 74, Muhammad Ali has done his fellow Americans, believers and non-believers alike, one last good turn.

This Thursday evening, an interfaith service will be held at the Atlanta Masjid of Al-Islam in memory of the greatest boxer ever to dance on canvas. Similar gatherings will be held in mosques across the country, a prelude to a Friday burial and a final, massive celebration in Louisville, Ky., Ali's hometown.

Former President Bill Clinton will be at the Kentucky event. Bryant Gumbel and Billy Crystal, too.

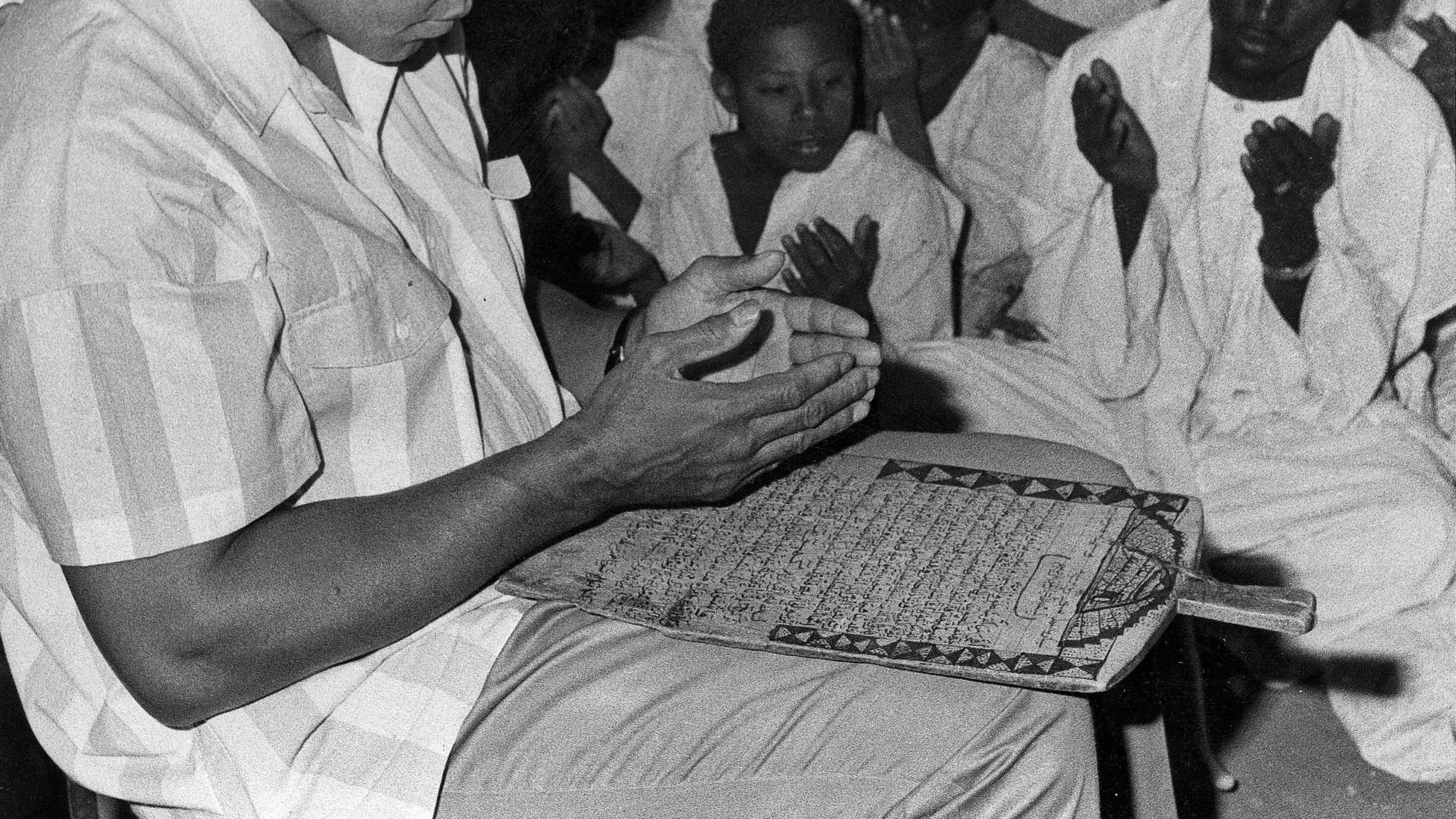

Each gathering, including the one here, will be an opportunity to remember that, once upon a time, the face of Islam in America belonged to a black youth whom we had watched grow into adulthood. And we weren’t afraid.

Before Sept. 11, 2001, before Barack Obama was vilified for his middle name, before a certain presidential candidate threatened to bar all Muslims from our shores, before there was an Internet that aimed its siren call of jihad at pockets of our youth, and before blood was spilt in Chattanooga, San Bernardino and elsewhere, Islam was an accepted — if exotic — patch on the American quilt.

In the U.S., the religion was personified by Ali, who was so popular he even had his own Saturday morning cartoon show. “When I would go to school as a boy, at Utoy Springs Elementary School, my name was acceptable because of Muhammad Ali. I can’t tell you what that meant,” said Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed — who is a Methodist, by the by.

“Muhammad Ali has been popular for decades, and he was a Muslim for decades,” said Edward Mitchell, executive director of the Georgia chapter of Council of American-Islamic Relations. Mitchell will be among the speakers at the Atlanta memorial service for Ali. “It’s an opportunity to remind people what they ought to already know,” he said.

Yes, perhaps we ought to know that. But religious tolerance doesn’t come naturally, or easily — not even to us. We forget that the Puritans who fled persecution in Europe weren’t willing to tolerate others once they arrived here. Dissidents were exiled or, in a few cases, executed. Even despite the First Amendment, one could argue that America didn’t take religious pluralism seriously until after World War II, when Adolph Hitler drove home the price of industrial-strength bigotry.

Tolerance and its brother, trust, are products of familiarity and shared interests. Atlanta’s first extended embrace of Muhammad Ali came in 1970 and was a matter of mutual dependency. Refusing the draft during the Vietnam War had caused Ali to be stripped of his heavyweight title and banned from boxing. He needed a state, with a big city, that lacked a boxing commission and so could allow him to compete. Sam Massell was still mayor at the time, but Atlanta’s black political structure was in its ascendancy and relished an opportunity to show its independence. And so Ali nailed Jerry Quarry in three rounds in the Municipal Auditorium, even if Gov. Lester Maddox didn’t approve.

“It was a protest not just against the nation, but against the nation, but the state,” said Plemon El-Amin, the retired imam of Masjid of Al-Islam in Atlanta.

But we also forget that the Islamic world didn’t immediately trust Ali as one of its own. The boxer originally announced himself a follower of the Nation of Islam, an American-born, race-based sect seen as heretical by most traditional Muslims, espousing the belief that whites were the creation of the devil. It denied the existence of an afterlife.

After the Nation of Islam’s leader, Elijah Muhammad, died in 1975, his son, Warith Deen Mohammed, led the organization into the folds of traditional Sunni-style Islam. Plemon El-Amin went with him, and so did Muhammad Ali. “I was making the same transition. He made it easily,” El-Amin said.

Three years later, Louis Farrakhan rejected the move and restarted the Nation of Islam. There was fear that Ali would follow him, El-Amin said. The boxer didn’t. “He was comfortable with global Islam,” the retired imam said. “Its universal soul called out to him.”

And so, that partnership was sealed as well.

The problem is that toleration, our willingness to share a world with those who are different, can’t hang on a single individual, even one who called himself “the Greatest.” The relationships that bind us must be lost and renewed, forgotten and remembered time and again.

On Monday, Gerald Harris, editor of the Christian Index, the longtime, official news outlet for Georgia Baptists, wondered out loud whether Islam was worthy of the religious liberty protections offered by the First Amendment. "Do Southern Baptists entities need to come to the defense of a geo-political movement that has basically set itself against Western civilization?" he asked.

The question carries double weight, given that the Georgia Baptist Mission Board was the force behind HB 757, the bill intended to protect Christian conservatives from the impact of the U.S. Supreme Court's gay marriage ruling. Gov. Nathan Deal vetoed it last month.

The day after Harris' column appeared, Mitchell, the executive director of the Georgia chapter of CAIR, invited the Baptist editor to attend a Ramadan interfaith dinner later this month. On Wednesday, Harris told my Journal-Constitution colleague Sheila Poole that he couldn't make it — but hoped to do so in July.

“I would be interested in finding out more about the Council on American-Islamic Relations. I’ve read about it,” Harris said. “It professes to be for religious liberty. I would like to know if they would be willing to have a Christian church built in Mecca. That would be a demonstration of religious liberty, I think.”