It seems the latest talking point from the left about GOP tax-reform efforts, specifically the Senate version of the bill, is that it will actually raise taxes on the poor. This is a perfect example of how to use partial information, flawed modeling and deceptive rhetoric to create a false narrative.

The basis of this claim is a score of the bill by the Congressional Budget Office that shows a positive effect on the deficit -- that is, a tax increase -- on those earning less than $30,000 starting in 2019, and for those earning less than $40,000 by 2025 (after which the bill's individual tax cuts expire, for the artificial purpose of reducing the bill's scored effect on the deficit). That sounds pretty bad, especially when higher earners continue to enjoy tax cuts, right?

Only if you completely disregard how those numbers were determined.

In truth, the only reason those numbers look that way is because the Senate bill includes a repeal of the Obamacare individual mandate. Now, as I've explained previously , this is not tantamount to "taking away" anyone's health insurance; anyone who wishes to continue buying insurance on the Obamacare exchanges would have exactly the same subsidies available to them. That's because the bill does not eliminate the subsidies. What it eliminates is the requirement, punishable by a tax penalty, that everyone buy health insurance. That would seem to increase deficits, because those tax penalties would no longer be paid. But the CBO says it would actually decrease deficits, because the government would no longer be paying a larger amount in subsidies -- in the form of tax credits -- to those who chose not to buy health insurance any longer.

The important words there are "chose" and "tax credits."

Once some people chose not to buy health insurance any longer, the amount of subsidies paid out in the form of tax credits to them would decline. But ignoring for a moment the wisdom of reducing the number of insured people, this is not at all the same thing as raising taxes on these people. The tax credits, after all, end up with the insurance companies to pay for premiums. Although the CBO for accounting purposes allocates the credits to the people who benefit from them, they don't lower people's tax bills. Nor do people have the choice of keeping a portion of the money to spend on things other than insurance. On the contrary, in many cases these taxpayers might have more money in their pockets if they don't have to incur the additional costs beyond the subsidies of buying the insurance. After all, if it doesn't cost them anything to have coverage, why would they stop getting it just because they were no longer required by law to have it?

Answer: They probably wouldn't. This most likely is another example of the CBO putting too much stock in the power of the individual mandate, which has led the agency consistently to overestimate how many people would become insured under Obamacare. (It also means most of the deficit "savings" from eliminating the mandate is probably bogus, but that's another debate.)

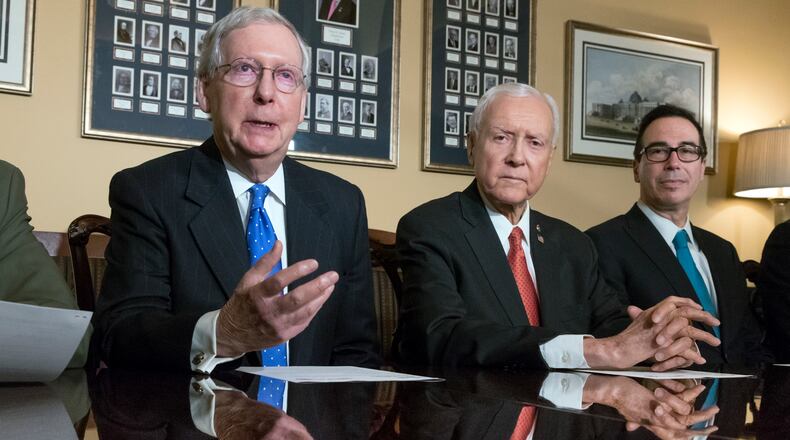

So the appearance of taxes rising on the poor is a complete artifice based on whether people would choose to stop buying subsidized health care if the government doesn't require them to buy it. But don't take my word for it. When Sen. Orrin Hatch asked the CBO for a score without counting the (supposed) effects of eliminating the individual mandate, here's what the agency sent him :

As you can see, so long as the individual cuts remain in place (through 2025), every income group has an aggregate tax cut. The only way that changes is if Congress and the president in 2025 allows them to expire. When the Bush tax cuts were due to expire several years ago, the lower rates were extended at the bottom end of the income scale but not at the top -- meaning it most likely isn't lower-income Americans who have to worry about the rates expiring. The certainty of permanent rates, the avoidance of a needless fight over extending them, and the honesty in budgeting of assuming they would stay in place in the end all argue for making the rates permanent.

Speaking of honesty: There are things to like and not to like about this bill, but it would be nice if Democrats and their allies could stick to those things without pretending it is something it's not.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured