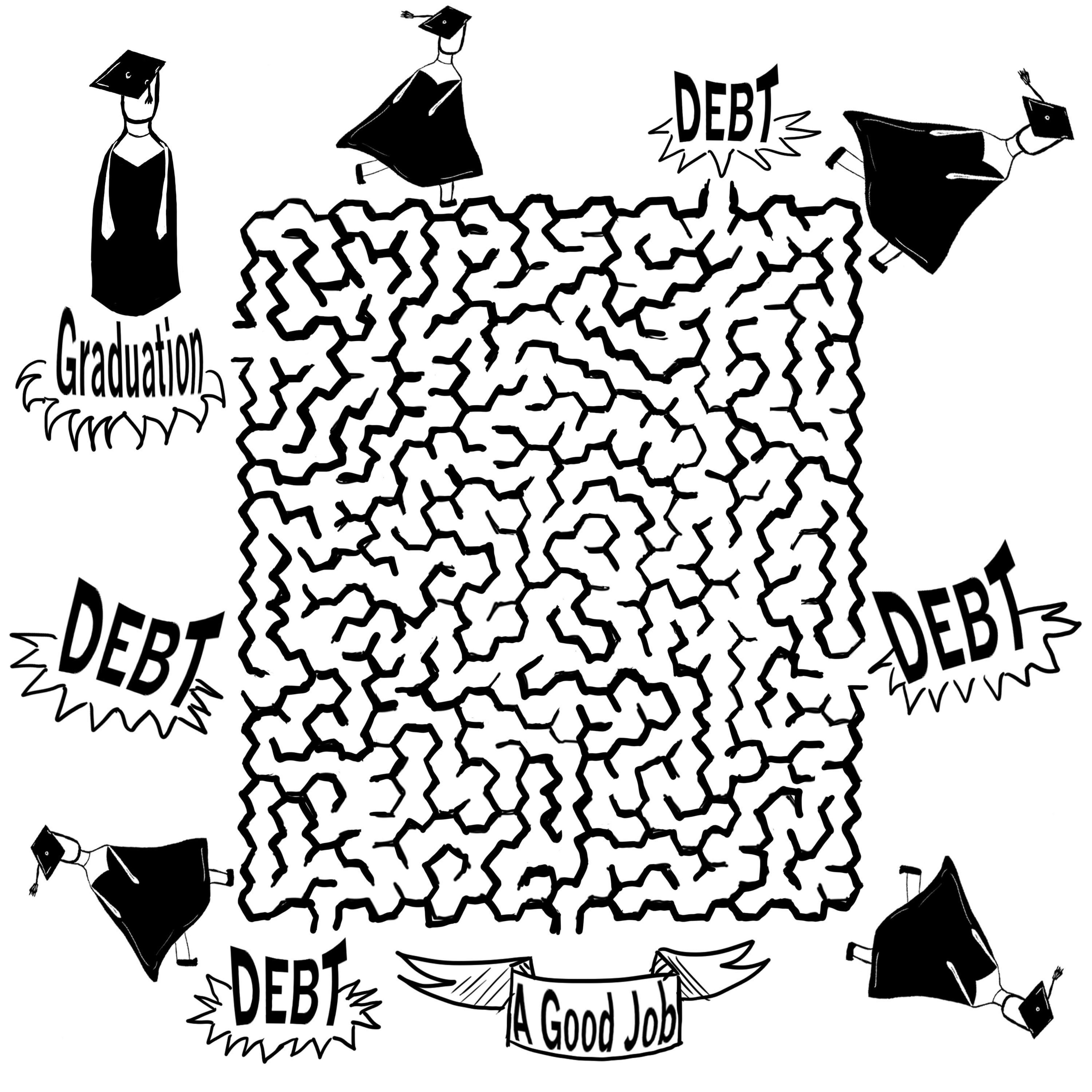

Should college be free or at least debt-free?

One of the few education issues to emerge in this presidential race has been free college as proposed by Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders. Sanders wants tuition-free public campuses in the model of several European countries. He also wants a substantial overhaul of student loan programs so more students can graduate without crushing debt.

Student loans have particular interest here in Georgia where 62 percent of college graduates leave campus with a degree and debt.

As the AJC reported in October:

At public and nonprofit colleges in 2014, seven in 10 graduating seniors had student loans. The average debt amount for those graduates was $28,950, a 2 percent increase compared to the class of 2013, the report by the Project on Student Debt at the Institute for College Access and Success found. The report includes a state breakdown showing the average debt for 2014 Georgia graduates reached $26,518, up from $24,517 in 2013.

Here is a debate on student debt by Olivia Alperstein, a 2014 Wesleyan University and the communications and policy associate at Progressive Congress, and Neal McCluskey, the director of the Cato Institute's Center for Educational Freedom. They wrote these counterpoint essays for InsideSources.com.

All College Should Be Debt-Free

By Olivia Alperstein

$1.2 trillion — that’s the estimated collective college debt total for this country.

College education should be debt free. Student debt not only burdens young people during college as they work to finance each semester but also affects post-graduation economic security.

Financial burden often becomes a factor when otherwise-fit students choose to drop out, and the consequences of late payments or defaulting on loans can affect credit scores for decades to come. We should focus on providing all students with equal opportunity to gain knowledge and skills to pursue careers of their choice. Debt shouldn’t affect a person’s ability to get a good education, and colleges and debt collectors should not profit from turning students into cash cows.

Like many recent college graduates, I take the issue of college debt personally. I had full financial aid, and I took work study jobs to support myself. I’m one of thousands of graduates across the country who benefited from the Perkins loan program, a federal low-interest loan option for low-income students. I took out loans only as needed and maximized my work study hours — and with the ideal circumstances in place, I will still end up paying around $12,000. I’m very fortunate.

I don’t have tens of thousands of dollars in debt. I never had to take out private loans, which tend to have exorbitant interest rates and whose collectors sometimes pose as federal agents and threaten people with jail if they don’t make payments.

Others two or three class years behind me are not so fortunate. The Perkins loan program was gasping for its last breath after Congress had refused to renew it. The authority to make new federal Perkins loans actually expired on September 30, 2014. In January 2016, President Obama revived it — sort of. Students who qualified for Perkins before or after 2014 will continue to borrow under the same terms, whereas those who enrolled or qualified after 2015 will have limited access to the program, thus bearing more of the financial burden.

Perkins also comes with a grace period, so you have some time after graduation to get a job and position yourself before you have to start making payments out of pocket. Other loans have interest accrue during your time at school, and payment is required immediately upon graduation — I know students who graduated in three years precisely because they felt they couldn’t afford another year of debt under these terms.

When I graduated in 2014, the unemployment rate for 18- to 29-year-olds was 9.1 percent. My half-generation graduated with the effects of the recession, with decreased employment prospects in many fields and increased competition for lower-salary positions.

The over-competitive job market has led to an unrealistic pool of applicants for short-term internships and jobs. Social Darwinists are probably rejoicing at this perfect storm of survival of the fittest, but in reality many incredibly qualified applicants with diverse experiences are falling into the black hole of the post-recession job market. For those barely making a decent wage to begin with, student loan payments become a significant financial burden.

Some argue that all low-income students should enroll in community college, where costs are less than half of most private colleges. That still leaves those students with thousands of dollars of debt, though, and telling low-income students to avoid going to Ivy League colleges is discrimination based on economic status. No one should be barred from elite college opportunities due to future debt.

Debt affects not only where people attend college but also whether they stay. Now, even among middle-class students who drop out, about one-third say they left for financial reasons.

Why does college cost so much in the first place? The Cato Institute agrees that college tuition costs have soared far too high, but Cato predictably blames the federal government for helping to create this situation. Its solution? Cut federal aid programs like Perkins and the Pell grant, a grant specifically aimed at low-income students and for which I qualified all four years of college. Let students struggle through college alone and carry the full cost of their education. That’s unsustainable and cruel.

Countries such as Germany have eliminated college tuition entirely. The least we can do is make college more affordable and forgive student loans.

I believe that education is a fundamental right and a vital tool for success in today’s economy. As salary expectations have dropped, a degree is more important than ever to guarantee a decent, livable wage.

College students are future leaders and innovators. We must ensure that all students have an equal opportunity to pursue their educational goals, and that means getting rid of college debt. The only debt students should graduate with is a debt to society, for which the only payment is a commitment to contribute to and improve the world around them.

Counterpoint: Debt-Free College? Maybe

By Neal McCluskey

The cost of college is almost certainly too high, and a consequence of that is alarming student debt. Does that mean our goal should be to make college debt free? Depends how you do it.

First, let’s be clear: While the cost of college is probably much higher than it should be, and millions of people enter but never finish, a degree still tends to pay off handsomely, with the average graduate making far more over her lifetime — some estimate $1 million more — than someone who ended their education after high school. Average debt for grads who took out loans — about $35,000 — is therefore a good investment in oneself, and even the lowest-income Americans would be welcome customers for lenders as long as they were demonstrably college ready and planned to major in a marketable subject.

This gets us to why debt-free college may not be a great idea. It would be terrific if college were debt free because covering the actual costs of one’s education was manageable without debt. But if higher education was made debt free because we were forcing taxpayers — people who do not reap the $1 million reward — to directly subsidize it, that would be bad.

A huge reason the price of college is so high right now is government “help.” The federal government has subsidized students for decades, allowing colleges to raise their prices at rates far in excess of household income and even healthcare, and encouraging students to demand ever-greater luxuries. Use other peoples’ money and your incentives to demand efficiency wither.

In just the last year studies from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and the National Bureau of Economic Research have found that very large parts of college prices are attributable to federal aid expansions, and other NBER research has suggested that all but the most academically oriented students put heavy value on “amenities” such as “student activities, sports and dormitories.”

So why not get states and the federal government to spend directly on colleges in exchange for schools charging less, or not at all? To different extents, that is what Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders have called for.

But subsidizing schools directly comes with even bigger problems than subsidizing students. While American higher education is wasteful and expensive, it is also the most vibrant, responsive higher education system in the world. Seventeen American universities are in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings’ top-25. None are from Scandinavia, which Sen. Sanders holds up as the ideal.

Similarly, the Center for World University Rankings puts 18 American institutions in the top 25, while the highest-ranked Scandinavian school — Sweden’s Karolinska Institute — comes in at 71.

The United States is also by far the most popular destination for people studying outside their home countries. No wonder the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research in Australia has ranked the American higher education system the best in world.

Why is U.S. higher education so good relative to the rest of the world? Because almost every other country runs higher education on the “government provides, you go free” model. The result is often poorly maintained infrastructure, big classes, hard to access professors and languishing students.

There’s also rationing. In Sweden, universities get 2.5 applications for every one available slot. Germany is infamous for tracking students into or out of higher education by a test called the abitur. In France, high school principals, essentially, decide whether a student gets to be on a college track, and the weeklong baccalaureate exam determines if they can go to a university.

The solution to these problems — our spiraling costs, just about everyone else’s moribund systems — is not more government money, but less. It is to phase out aid and have people pay with their own funds, or money they get voluntarily from others. Then institutions would be unable to raise their prices with impunity, students would demand fewer expensive frills, while the system would retain the freedom essential to innovate and respond to ever-changing student needs.