Miami’s Museum of Graffiti celebrates ephemeral artform

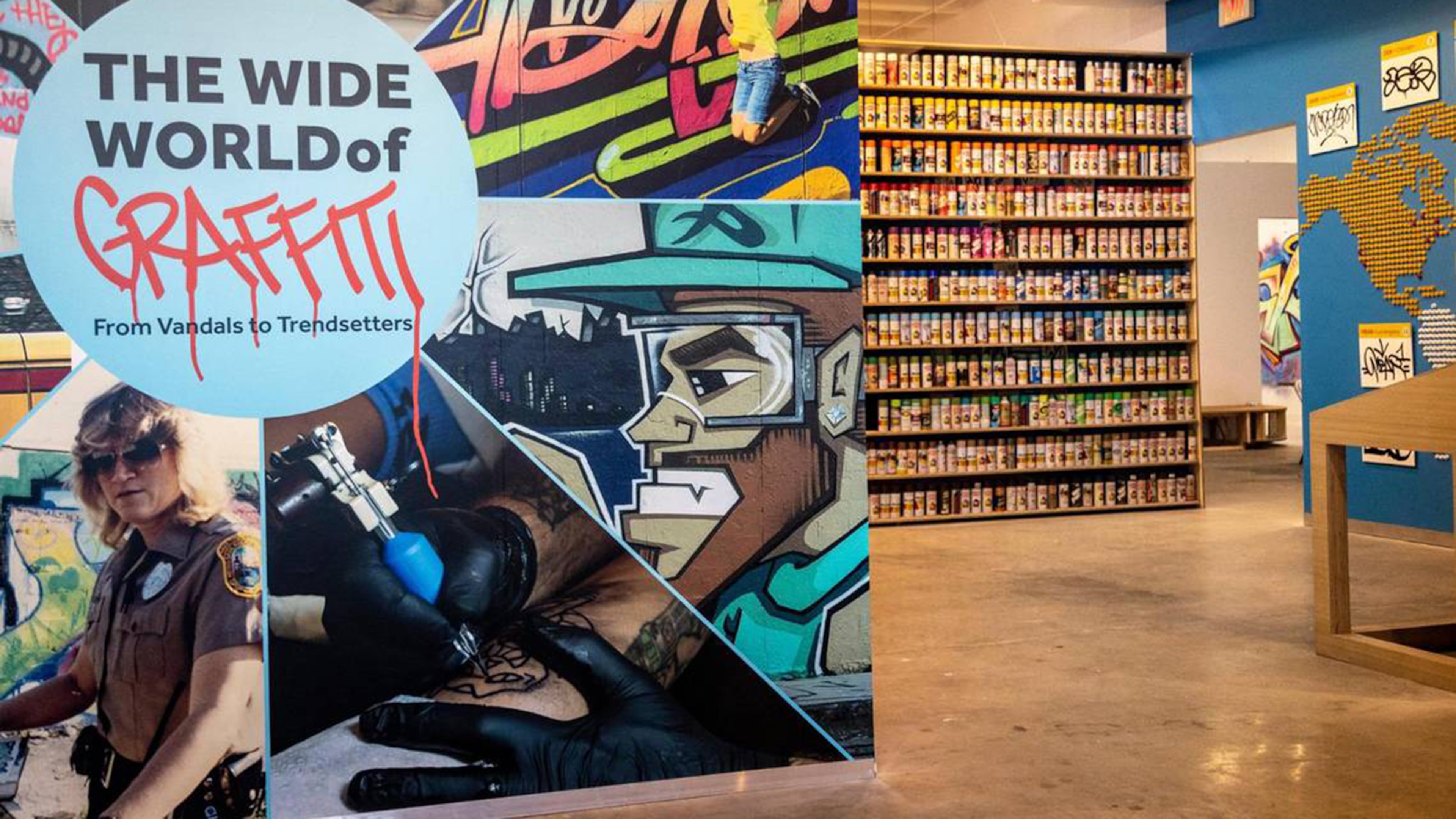

MIAMI - Graffiti writers: Artists or vandals? It’s a question explored at the Museum of Graffiti, which moved into new, 5,000-square-foot digs in March. Located in the art-centric Wynwood neighborhood, the institution celebrates some of the world’s most recognized graffiti writers with permanent and rotating exhibitions, plus 11 murals on its exterior walls.

Among its permanent exhibitions is “Cities versus Vandals” featuring a replica of a Philadelphia police car door emblazoned with the tag “Cornbread,” used by Darryl McCray, one of the first modern graffiti writers.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, the mischievous teen plastered his name all over the City of Brotherly Love countless times, but he always managed to elude police. Painting a police car was a taunting, in-your-face insult to the authorities that had long pursued him, but it was one of his tamer stunts. He also tagged the Jackson 5 plane.

His piece de resistance was his undoing. He painted “Cornbread Lives” on an elephant in the Philadelphia Zoo to disprove a newspaper article that erroneously announced his murder. He was promptly arrested.

A collection of newspaper articles from around the country documents decades of collective outrage toward those defacing public property. Heavy-handed punishments, including prison time, were handed down to these renegade artists, even those who, unlike Cornbread, didn’t write on living, breathing canvases.

Alan Ket (born Alain Mariduena) and Allison Freidin founded the museum in 2019. They wanted to chronicle the history of modern graffiti, an artistic movement that blossomed in New York’s Black and Latino neighborhoods in the 1960s, and document its expansion into a global art revolution that became ingrained in hip-hop and pop culture and now proliferates in advertising, fashion and design.

Like traditional museums that carefully preserve and safeguard art in climate-controlled galleries, the Museum of Graffiti’s objective is to conserve and curate an artform that is inherently ephemeral by nature.

When it comes to the “artists or vandals” question, Ket is naturally in the “artists” camp. It’s not surprising since the 51-year-old spent much of his youth spray-painting bright, flamboyant images on subway trains in 1980s Brooklyn, proud to have a hand in the “coolest and most exciting art movement of my lifetime.”

Graffiti writers of that era got a thrill out of creating mobile art that would travel throughout New York’s five boroughs.

The act of illegally painting one’s name on public property is a way for marginalized youth to literally leave their mark on a city, says Ket.

“It comes from the drive to be recognized, to be heard, to be someone in a big city, to matter for a little while,” Ket said. This was especially true in a pre-social media world.

Museum space is dedicated to the tradition of painting subway and freight trains. A series of photos, many taken by journalists, chronicles the range of styles and subject matter that appeared on trains in cities around the world from the 1970s to the early 2000s.

New York’s clean train policy of the 1980s removed graffiti-covered trains from service. By 1989, the days of admiring your “burner” (a large, elaborate piece) as it zipped through the city, were a thing of the past.

The museum gives visitors the tools and vocabulary to understand the rise of graffiti as an art form.

The manifold graffiti letter styles and how they evolved are explained. Early graffiti letters were written in conventional fonts, but over time, writers took artistic liberties, creating embellished, distorted lettering that was sometimes barely legible.

No commentary on graffiti styles would be complete without a mention of Michael Tracy, known as Tracy 168. He pioneered the wild style, a form of highly stylized interlocking letters. He also introduced cartoon characters into his colorful, chaotic pieces.

“Global Tags,” an exhibit featuring a map made of spray can caps, highlights the unique signatures of prolific graffiti writers from around the world, including the legendary Uzi, who gets his name up on the streets of Stockholm.

The “Wide World of Graffiti” exhibition introduces Lady Pink (Sandra Fabara), known as the First Lady of Graffiti. The rebellious teen broke into the boys’ club in 1979, leaving a colorful trail all over New York.

Fast forward 40 plus years, and she’s gone from subway train to blockchain. A screen depicts her NFT (non-fungible token), a digital asset that is collectible and unique bearing a serial number stored on the blockchain to prove ownership. NFTs are especially useful to graffiti writers because of the impermanence of their art.

Lady Pink’s NFT is based on a mural she painted on the outside of the museum in 2020 to celebrate young activists fighting for a fairer immigration policy, gender equality and justice for the LGBTQ community. The mural is gone, but it is digitally preserved. On the screen, a woman of color with fluttering butterfly wings holds a torch in one hand and a baby in the other.

Young graffiti writers are notoriously disdainful of old guard institutions such as art schools and museums, but some do crossover. Lady Pink’s work has been exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Groningen Museum of Holland among other art institutions.

She’s proof that today’s graffiti “vandals” could be the respected artists of the future.

Just steps away from the Museum of Graffiti is Wynwood Walls, an outdoor museum of street art. Established in 2009, the art is ever changing, so it never gets old, even for locals.

On a recent visit, a larger-than-life Dalai Lama painted in red and white peers enigmatically through square glasses. At the other end of the expansive mural, civil rights leader the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. looks pensive and determined. Between these two social justice advocates is a smiling man in a cowboy hat that’s less recognizable – the late Tony Goldman, an artist and founder of Wynwood Walls.

The mural by Shepard Fairey pays homage to the visionary developer that turned a warehouse district in an urban neighborhood into a celebration of street art that incorporates the artist’s recurring themes of oppression and inequality.

Fairey believes artists have a responsibility to be a “voice for the voiceless,” especially during these turbulent times.

“I’m always trying to use my art to create important conversations,” Fairey said. “This is a moment where there isn’t just one conversation to have.”

In a space where every piece competes for attention, Brazilian artist Eduardo Kobra’s “Ethnicities” is a standout, and not just because of its monumental size. Hyper-realistic images of five children from five continents are overlayed with geometric shapes in a kaleidoscope of colors. It conveys the artist’s message that hope for humanity lies is in the next generation.

As visitors mill around taking Instagram-worthy photos, one thing becomes clear. Mainstream attitudes toward street art have changed. The writing is on the wall.

If You Go

Museum of Graffiti. “Bits and Pieces,” a solo show of new works by graffiti writer Ghost, is on exhibit through mid-July. $16. 276 N.W. 26th St., Miami. 786-580-4678, www.museumofgraffiti.com

Wynwood Walls. Guided and self-guided tours available. $12. Tours $17-$50. 266 N.W. 26th St., Miami. 305-576-3334, museum.thewynwoodwalls.com

Accommodations

Hilton Aventura Miami. This new hotel features seasonal art exhibits. $175-$250. 2885 N.E. 191st St., Aventura, Florida. 305-466-7775, www.HiltonAventuraMiami.com

Faena Hotel Miami Beach. A luxury oceanfront hotel with stunning art throughout. $580 and up. Catch TRYST cabaret show at Faena Theater. $95 and up. 3201 Collins Ave., Miami Beach, Florida. 305-535-4697, www.faena.com

Dining

Joey’s Wynwood. Modern Italian cafe near Wynwood Walls. Entrees $14-$36. 2506 N.W. 2nd Ave., Miami. 305-438-0488, www.joeyswynwood.com

Gala. Tucked inside the Hilton Aventura Miami hotel, this restaurant features South American flavors that can be enjoyed indoors or on the patio. Entrées $21-$42. 2885 N.E. 191st St., Aventura, Florida. 305-466-7775, www.HiltonAventuraMiami.com

Tourist info

Greater Miami Convention and Visitors Center. 701 Brickell Ave., Suite 2700, Miami. 1-800-933-8448, www.miamiandbeaches.com