SXSW: Why food waste is your problem, too. (Yes, you.)

On a farm in Vermont, the circular economy is thriving.

That's the term for an industrial system that produces no waste, and though closed loop systems are a goal for many manufacturing companies. In the food industry, gaps in the system have led to massive quantities of food waste.

Just how massive? More than 133 billion pounds of food, about 40 percent of the amount of food that moves through the U.S. food system.

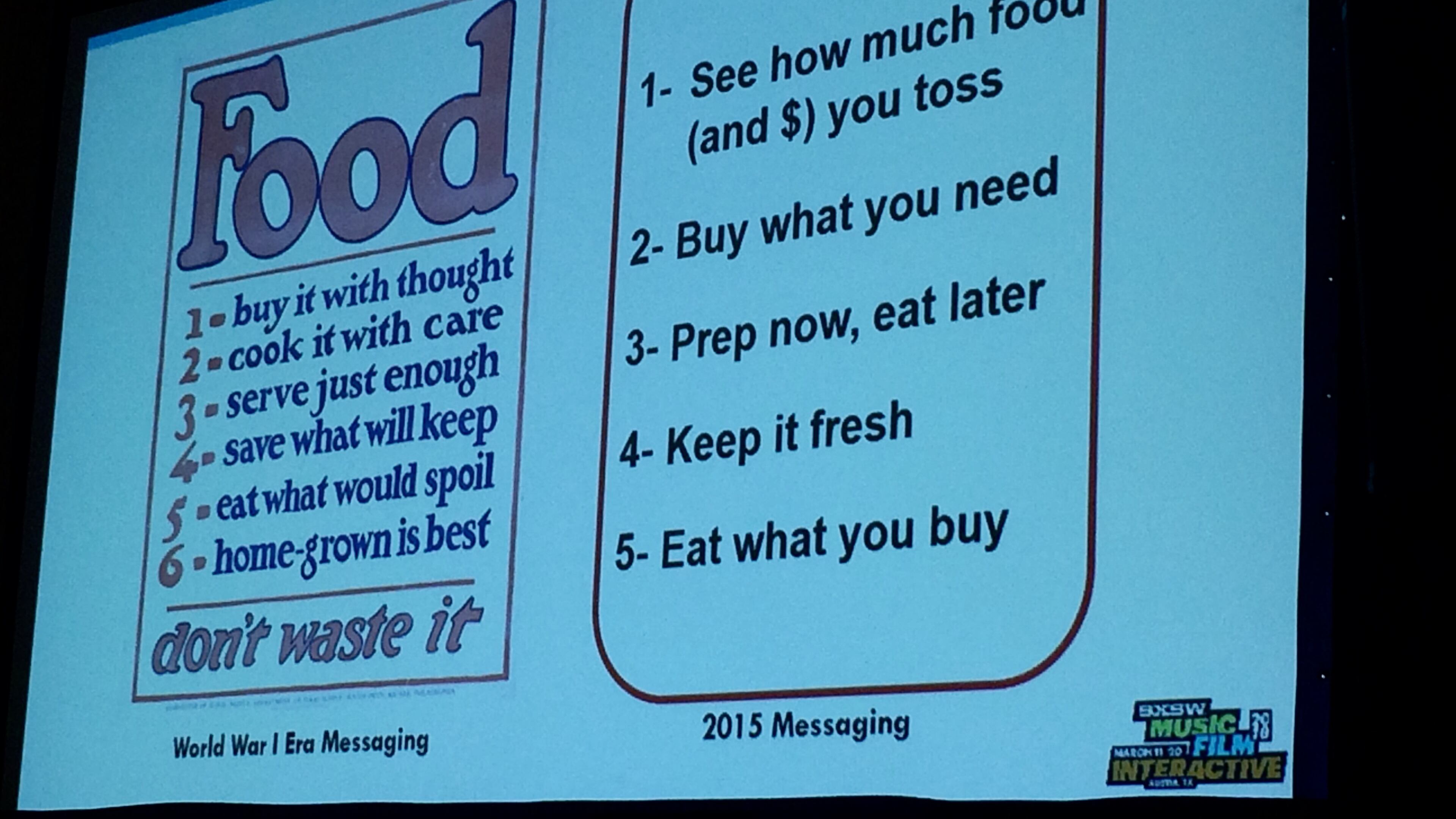

We’ve seen a major push in the past few years for consumers to love their leftovers, buy only what they need, compost the food waste they do produce and, in the face of details about their inaccuracy, even ignore expiration dates.

So what can we learn from a dairy farm in Vermont about reducing food waste? Farmer Marie Audet, who on Sunday joined panelists from Feeding America, Kroger and the Environmental Protection Agency, explained how they’ve tweaked their farm to create more energy than it uses.

The 130 or so cows produce milk for sale, but their waste is converted into energy, and the byproducts of that process are using as fertilizer for the soil and bedding for the cows. Audent said that by converting that waste into fuel, they produce enough energy for 400-500 homes.

It isn’t enough to make safe, affordable milk any more, she said. Today, she has to do so in a way that has as little environmental impact as possible. Twenty percent of her cows’ diet comes from food waste, including pellets made with citrus pulp leftover from juicing or spent grains from beer brewing.

At Kroger, the largest traditional grocer in the U.S. that has only a few locations in Texas, the store donates millions of pounds to food banks in the Feeding America network. Most grocer stores donate their excess food to food banks, but Kroger takes it a step further by turning food it can’t donate into biogas, a compressed natural gas that powers trucks and stores.

But one of the greatest barriers to reducing food waste is changing consumer expectations. Suzanne Lindsay-Walker, the director of sustainability with Kroger, said that they have to meet customer demands for the perfect shiny apple but that many stores now sell imperfect produce at a reduced price. “Those cultural norms are starting to shift,” she says. “We all have a part to play in this.”

The panel moderator, Ashley Zanolli with the EPA, talked about how different kinds of cooks contribute to the food waste problems, from the adventurous overachieving cook who might buy too much at the store and not be able to use it all before it goes bad to the cautious cook who tosses anything even close to an expiration date or who looks at a piece of produce past its prime and throws it away, rather than find a way to utilize it in a soup or a smoothie.