In trouble again, Larry Brown finds forgiveness

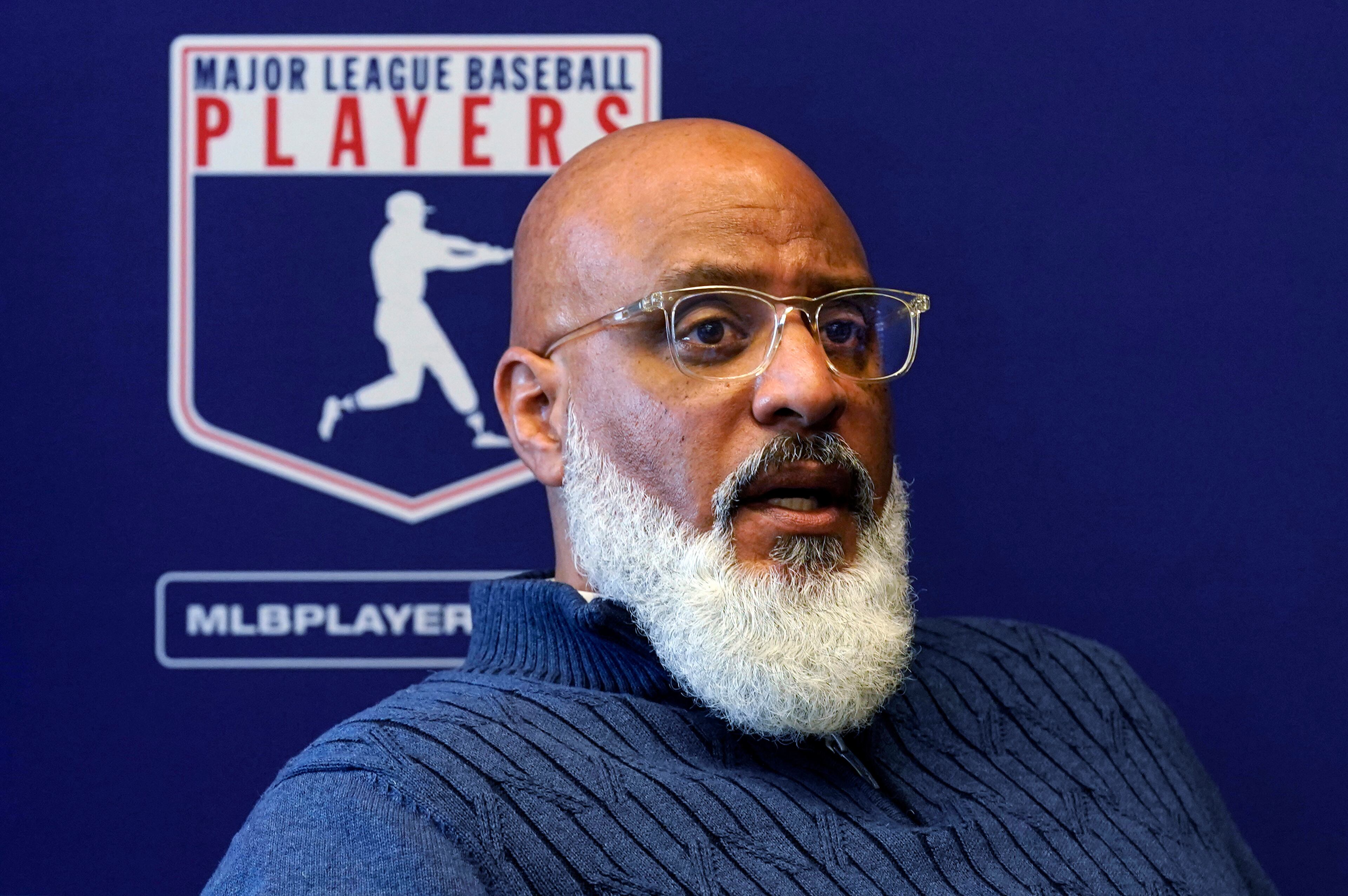

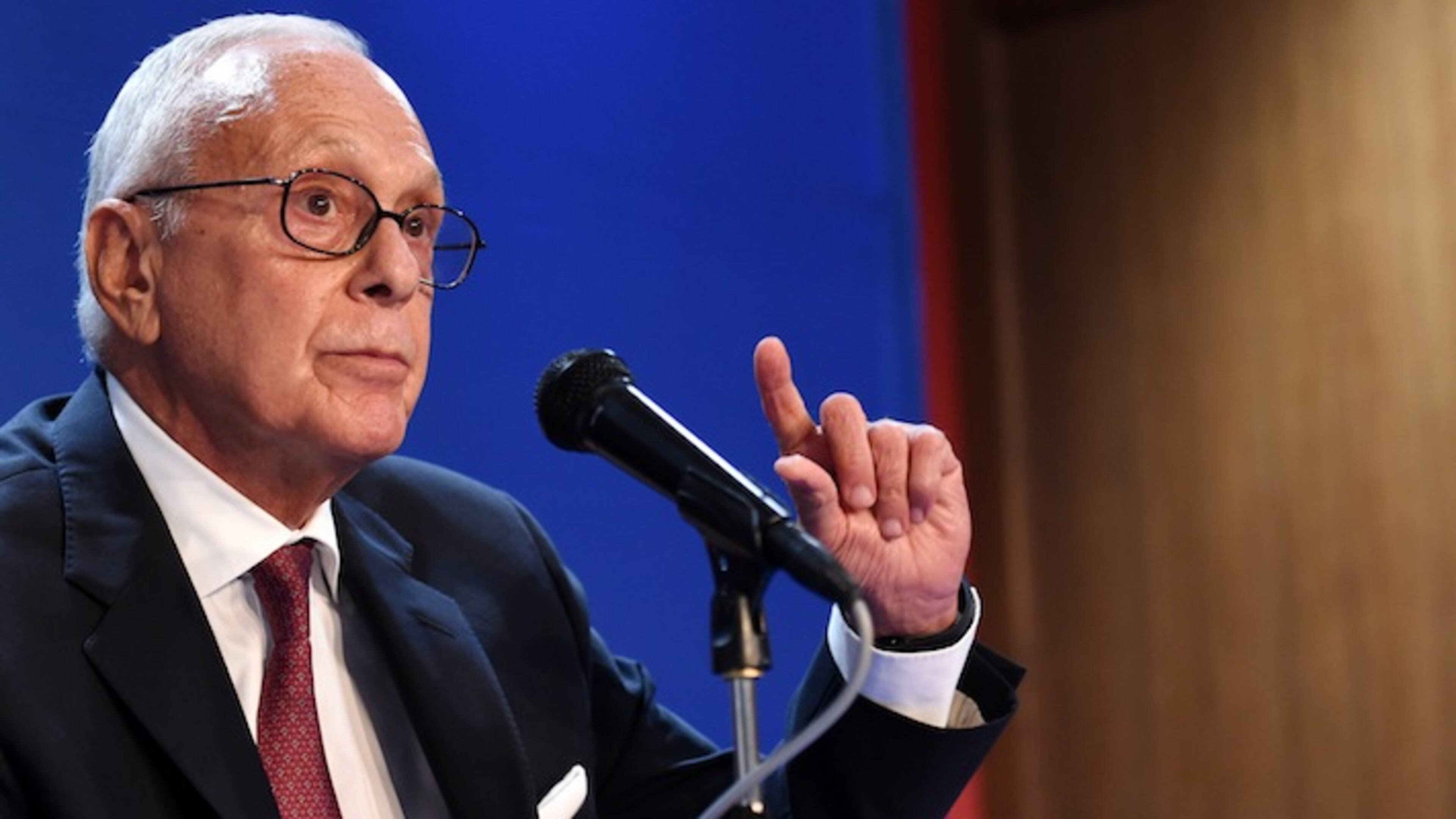

Larry Brown, a much-traveled Hall of Fame basketball coach and the current pride of Southern Methodist University, is a fool for love.

Asked by NCAA investigators about his young assistant, a woman who committed academic fraud to help one of his players pass an online course, Brown replied, “She cared deeply about me,” according to an NCAA report. Asked by the same investigators about Keith Frazier, the player in question, Brown confessed that he “loved” the kid.

Frazier, by the way, was a former McDonald’s all-American and the fourth-leading scorer on Brown’s nationally ranked team at season’s end.

Brown’s continuing problem, he told the investigators, is that he gets all bollixed up when he’s dealing with “people that I really care about.”

You could find this touching to listen to, if you severed a cerebral artery. Brown has coached three big-time college teams, and now all three have landed in the despond of NCAA sanctions. On Tuesday, the NCAA suspended Brown for nine games this season and barred his team from competing in the 2016 postseason.

Fortunately, in his old age — Brown is 75 — he has found an extremely forgiving employer.

SMU officials, whose university code of ethics stresses “integrity in work” and “accountability,” issued this statement Tuesday: “The university disagrees with the conclusion of the committee that Coach Brown failed to promote an atmosphere of compliance.”

University officials might challenge the NCAA penalties. That effort could be complicated by inconvenient facts: Brown covered up the academic fraud and lied about it to the NCAA. Don’t take my word for this — here are his words: “I don’t know why I lied,” Brown told investigators, according to the NCAA report.

There is a temptation to dismiss all of this as laughable. Major college athletics are muddy waters, which millionaire coaches dive into and emerge from each year with top-ranked recruits. How this happens, and whether these teenagers will remain in school long enough to pass a course or three, is left to mystery.

If we are naive, we believe. Otherwise, we root and cheer and pretend.

The NCAA often proves hapless because very large and powerful colleges make millions of dollars off football and basketball and because the subterfuge is often impressively complicated. When former athletes at the University of North Carolina sued the NCAA in January, arguing that their highly ranked university had provided them with nothing like an education, the association shrugged.

The NCAA’s lawyers, with breathtaking sleight of hand, argued the association had no legal responsibility “to ensure the academic integrity of the courses offered to student-athletes at its member institutions.”

Yes, well.

The NCAA is an obtuse athletic cop. Brown, a reprobate who failed to execute basic oversight of his staff, will miss nine games. His players, all but one of whom apparently complied with the university’s academic requirements, will lose the chance to compete in the postseason, and so, too, attract pro scouts in this country and overseas. At stake, for these athletes, is hundreds of thousands of dollars, if not millions should they make the NBA.

You call B. David Ridpath, a professor of sports administration at Ohio University and a longtime reformer in intercollegiate athletics, and ask about the inequity. He sighs audibly.

“I really hate that the system is set up so that the kids suffer,” he said. “Coaches like Brown should be terminated and never rehired.”

He suggests an alternative so neat and morally fair that you would place a large bet that the NCAA and its member colleges would sprint from its embrace: When sanctions fall on a coach, let every one of his players immediately transfer to another college. Those who wish to remain could retain their scholarships, whether or not they bounced a ball or threw a pass again.

As for the universities, Ridpath is a Jacobin. He would let the guillotine fall not on the coaches but on the athletic directors and college presidents. No innocents here.

SMU’s culpability is impressive. It established a special faculty committee to examine athlete applications. As the university’s athletic aspirations are boundless, it’s fair to assume this committee was not endlessly demanding.

Yet credit should fall where due. The committee took a look at Frazier’s checkered transcript and denied him entry to the university.

So the system worked until the SMU provost overturned it. According to the NCAA investigative report, the provost made an “extraordinary exception” that was “based on the broader university perspective and needs.”

I asked SMU spokesman Kent Best about the nature of those needs. In an email, he went on about “holistic” criteria. The provost is like a hawk on the hunt for those students who can make a special contribution “academically, personally, musically, athletically and so on.”

A cello player with a 45-inch vertical leap would be wonderful.

SMU was coldly realistic about the nature of the man it had hired. The university acknowledged to investigators that it was concerned about Brown’s 25-year hiatus from the college game and his honed and proven lack of understanding of NCAA rules. It placed the compliance director’s office in the same building as Brown’s office. This director met with him every day, traveling with the team, attending practices, eating meals.

This sounded less like a compliance director than a human ankle bracelet.

Yet, and still, Brown stumbled.

“I used terrible judgment,” Brown told investigators.

“There is no excuse for not going to” the athletic director, he said, when the student-athlete “told me he didn’t do this online, the course.”

Fortunately, Brown is a resilient man. When the NCAA released its report detailing his misdeeds, he was ready with his own counterstatement.

“I am saddened and disappointed that the Committee on Infractions believes that I did not fully fulfill my duties,” he said.

Oh, Larry, Larry, you old lover boy, it turns out you have a sense of humor, too.