Would a Trump trial during election be interference or due process?

On Election Day next year, the Fulton County jurors sitting in judgment of Donald Trump may have some decisions to make: should they take time off from court to cast a vote in the presidential election? And, if they do, will they vote for the defendant or against him?

The unheard-of, almost unimaginable scenario is entirely possible. Trump is, after all, far and away the Republican Party’s presumptive nominee. And District Attorney Fani Willis is proposing an Aug. 5 starting date for his trial and says it will run into 2025.

The issue came to a head during a daylong hearing on Friday before Fulton County Superior Court Judge Scott McAfee, who is presiding over the case and will have to decide when Trump’s trial will begin.

Steve Sadow, Trump’s lead Atlanta lawyer, strongly opposed the trial taking place in the weeks leading up to and including Election Day.

“Can you imagine the notion of a Republican nominee for president not being able to campaign for the presidency because he is, in some form or fashion, in a courtroom defending himself?” Sadow told McAfee. “That would be the most effective election interference in the history of the United States.”

Sadow added, “I would hope the state would understand that if the Republicans believe he should be the nominee that he should be given the same fair chance to campaign ... as the democratic nominee, which of course at this point appears to be President Biden.”

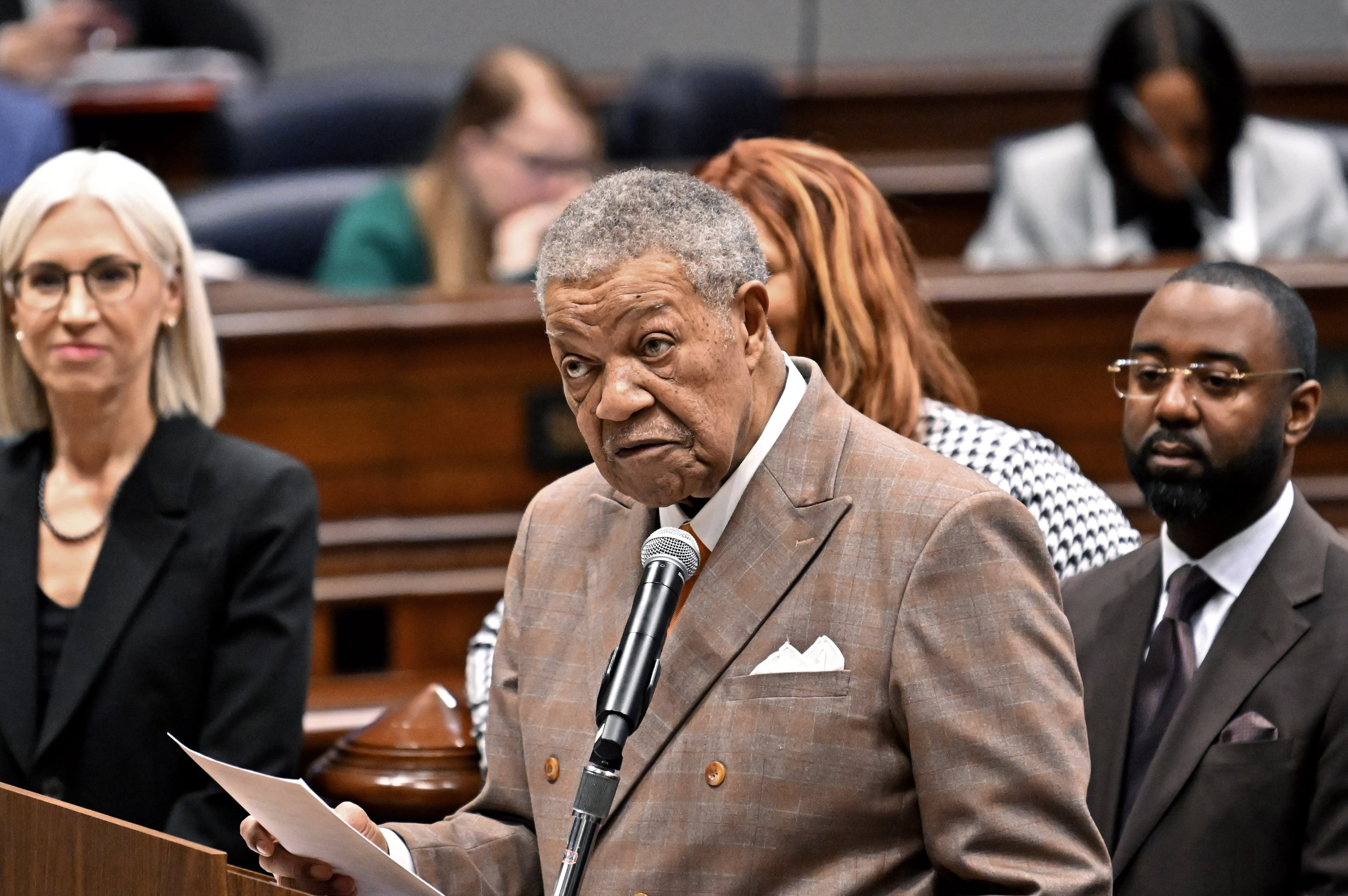

This led McAfee to pose a question to special prosecutor Nathan Wade. “What would be the state’s response that having this trial on Election Day is election interference?” the judge asked.

“Let’s be clear,” Wade replied. “This is not election interference. This is moving forward with the business of Fulton County. I don’t think that it in any way impedes defendant Trump’s ability to campaign or do whatever he needs to do in order to seek office.”

Prosecutors, Wade said, want to stick with the Aug. 5 trial date.

A dilemma with no precedent

The possible scenario of the trial underway on Election Day raises all sorts of questions. Can you vote for Trump for president and later find him guilty? Can you vote against him and later find him not guilty?

“This is a dilemma that no juror or any defense lawyer or prosecutor has ever faced before,” said Atlanta lawyer Jack Martin, who is following the case. “At first blush, a vote for a candidate would seem to be inconsistent with a vote to convict. But if the evidence is there, the duty of the juror is to follow the law.”

During Friday’s hearing, McAfee added some more potential twists. What if Trump is not the GOP nominee? he asked. “I think that’s a very low assumption,” Sadow responded, noting Trump’s commanding lead in the polls. Still, he acknowledged, if that comes to pass “I think it changes the perspective across the board.”

McAfee then asked, What if Trump is elected president in 2024, can he stand trial after he’s sworn in in 2025?

Not a chance, Sadow replied. “I believe that under the supremacy clause and his duties as president of the United States, this trial would not take place at all until after he left the term of office.” (The Constitution’s supremacy clause dictates that federal law is the “supreme law of the land.”)

Attorney Norm Eisen, who has written extensively about the Fulton case for the Brookings Institution, said Sadow may not be correct.

“The supremacy clause likely does not bar prosecution of a sitting president,” Eisen said. While the U.S. Supreme Court has not decided that question, its precedents have determined that “sitting federal officials, including presidents, are not above the law, including state laws and criminal ones.”

Insurrection or rebellion

There’s nothing that disqualifies someone running for president if he or she has been indicted or is on trial for the offenses Trump faces here.

To be eligible to be president, a candidate must be a natural-born citizen of the U.S., be at least 35 years old and have been a U.S. resident at least 14 years. The only disqualifications under the Constitution’s Fourteenth Amendment is for candidates who “shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion.”

It’s unclear if the 13 felony counts Trump is facing in Fulton County, which range from racketeering to conspiracy, would meet that constitutional benchmark even if he is convicted.

In a separate federal election subversion case, Trump is facing four charges that fit more neatly under the umbrella of insurrection or rebellion, such as conspiracy to defraud the United States by attempting to overturn a legitimate election. That trial is scheduled to take place in March. But even if Trump is convicted, it’s likely the decision would appealed, meaning things could still be murky when Fulton County moves forward.

Even someone who’s been convicted of a felony can run for the country’s highest office. In 1920, Socialist Party candidate Eugene Debs ran for president – and got 3.4 percent of the vote – while serving time at the U.S. Penitentiary in Atlanta for a sedition conviction.

Presidential historian David Greenberg, a Rutgers University history professor, said a trial during the presidential election is going to create all kinds of problems that would need to be sorted out.

“But I actually think it makes more sense to try to have the trial before the election,” Greenberg said. “After the election you have the possibility that Trump wins. Then he would no doubt argue for delaying the whole thing until after his presidency.”

Even though it would be messy to have the trial during election season, Trump, then the likely GOP nominee, would still be a private citizen up until the time if and when he is elected, Greenberg said. If Trump loses, “that would seem to simplify things, but that’s a big question mark.”

Election interference?

Former Gwinnett County District Attorney Danny Porter noted that the Justice Department steers clear of bringing charges and holding trials of public officials shortly before their elections. But he believes that policy “worked against the public interest rather than in favor of the public interest.”

For that reason, “I wouldn’t wait,” he said. “I think I would try to push it through, because those political issues are all out there on the table anyway.”

Josh McKoon, chair of the Georgia Republican Party, echoed Sadow’s remarks that Willis’s prosecution “is in and of itself an attempt to interfere in the lawful conduct of our elections.”

McKoon, a Columbus lawyer, added, “If there was any doubt that the Fani Willis prosecution is nothing more than a reckless prosecutor seeking political advantage for her party, scheduling the trial within 90 days of the election should remove that doubt. The Willis prosecution is wrongful, politically motivated and absolutely unconstitutional.”

Last month, at The Washington Post Live’s Global Women’s Summit, Willis said she fully expects Trump’s case to go to trial and that it will take many months, stretching into “the winter of the very early part of 2025.”

When asked about the trial possibly lasting through Election Day and perhaps even through Inauguration Day, Willis responded, “I don’t, when making decisions about cases to bring, consider an election cycle or an election season. Does not go into the calculus.”