Opinion/Solutions: How one community college is improving graduation rates

When Precious Johnson enrolled at Ivy Tech Community College in Indianapolis, she was terrified. It had been years since she graduated high school, and she was a single mom raising a son with autism.

“I was trying to figure out how to juggle this with my son,” Johnson, 40, recalled recently. “How am I going to do this homework? I still have to go to work in the morning.”

The challenges Johnson faced might be unusual at many four-year college campuses.

But community colleges across the country are designed to educate students like her — adults with complicated lives and responsibilities outside of school.

For a long time, Indiana’s community college system was among those that seemed to be failing those students.

When Johnson earned her associate degree in 2014, she was defying the odds. Less than 30 percent of her peers earned degrees or certificates six years after enrolling. And fewer than 1 in 20 students graduated from Ivy Tech on time.

But over the last decade, Ivy Tech, which serves about 74,000 students across the state, has made steady gains in completion rates. Two-year completion rates at Ivy Tech steadily improved from a dismal 5 percent for students who began in 2012 to 14 percent for the most recent cohort.

Ivy Tech, like other community colleges across the nation, has something of a dual mission.

On the one hand, it needs to serve its students. But it is also an essential tool for economic development, particularly in Indiana, where there are more jobs that require postsecondary education than qualified workers.

The community college system has seen significant declines in enrollment in recent years, reducing the number of qualified workers it educates. Improving outcomes for students who do enroll is another way Ivy Tech can help educate more workers — and prepare more people for good jobs.

Leaders at Ivy Tech point to several changes Indiana’s system has made over the years as it embraces practices that are backed by research or have shown success at other community colleges around the country.

Remedial education was one of the first and most substantial areas overhauled. These courses typically cover the same material as high school and don’t offer college credit.

Because remedial classes didn’t appear to be working, Ivy Tech restructured remediation, which is also known as developmental education, to allow students to take essential college-level courses as soon as they enrolled and push fewer students into remedial classes.

That transformation was part of a national movement.

Susan Bickerstaff, a researcher at the Community College Research Center at Columbia University, said developmental education had some problems. For starters, the placement tests schools used to check if students were ready for college-level math and English weren’t very reliable.

“Under the old system, we were just placing too many students into developmental education,” Bickerstaff said.

So, Ivy Tech made it a lot easier for students to show they were ready for college-level work, using evidence such as high school grades and scores on college admission tests. Now, students who are placed into remedial classes have the option to study and retake the assessment.

Those changes led to a staggering decline in remediation.

The number of Ivy Tech students identified as needing remediation dropped to about 13 percent in 2019 from about 67 percent in 2012, according to data from the Indiana Commission for Higher Education.

“It’s an enormous success for us,” said Kara Monroe, who was provost at Ivy Tech from 2018 to January. “It marked a significant turnaround, at least in community colleges, about the way we talked about … student success.”

For students who need help, Ivy Tech embraced a model called corequisites, which allows students to simultaneously enroll in developmental and college level math and English classes.

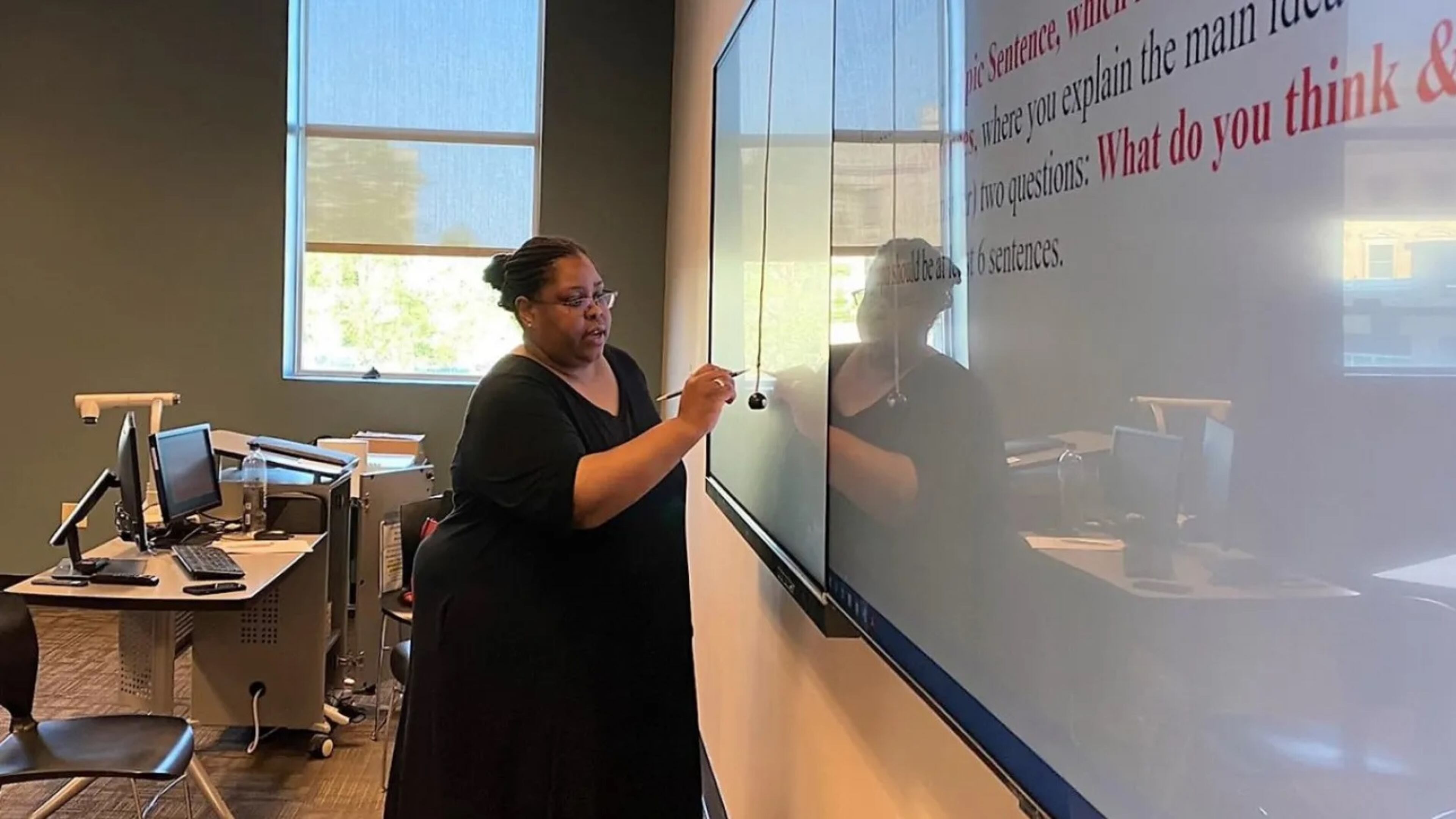

That’s the approach in Tiffani Butler’s English class.

English 111 is the “bread and butter” of the department, because most students must take it to earn their associate degrees, Butler said.

It’s a college-level class. But if students need remediation, they take a corequisite class to “help give them the support that they need to be successful,” Butler said.

One of the students in both classes is Moise Toussaint, who emigrated from Haiti.

“I’m very, very motivated to achieve this goal,” said Toussaint, who needs to pass English for the Ivy Tech nursing program. But it’s a challenge to keep up with the pace.

“It’s very fast. And you have to do a lot of stuff at the same time for both of them,” he said. “Then I have work too; I’m working at the same time.”

The class is a sprint for Toussaint because it’s only eight weeks long, rather than a traditional 16-week session. That’s another change that Ivy Tech embraced a few years ago: It shortened courses in a bid to keep students from dropping out and help them finish courses sooner.

The eight-week courses can be hard for students who are returning to school after years away, because it can take time to learn the skills they need to succeed as students, Butler said. Some students, for example, don’t even have laptops when they enroll.

“For students that are focused and ready for it, an eight-week format is wonderful because it does get them in and get them out,” Butler said. “But it’s not for everyone.”

Ivy Tech Provost Dean McCurdy, however, said that’s one of the changes that has helped the community college system continue to improve outcomes for students. Students are less likely to have a class interrupted by a problem outside of school when taking shorter courses.

Next semester, about three quarters of courses Ivy Tech offers will be eight-week sessions.

The system is also looking for new ways to improve outcomes, such as incentivizing students to take steps that help them succeed. Those include meeting with an advisor and filling out the financial aid application.

The changes at Ivy Tech have fueled dramatic gains.

But even though on-time completion rates have improved to 14 percent, there’s a long way to go.

Dylan Peers McCoy is an education reporter for WFYI, a PBS member station in Indianapolis. This story appeared on Chalkbeat, a nonprofit news organization committed to covering one of America’s most important stories: the effort to improve schools for all children.

About the Solutions Journalism Network

This story is republished through our partners at the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous reporting about social issues.