Opinion: I see double jeopardy in climate change, poor health

Mary is a 50 year-old widow and mother of three from the Atlanta metro area. She struggles with high blood pressure and asthma, and lives in an older home that floods in heavy rain. Mary works two part-time jobs -- one at an industrial plant – and often walks to work, given high gas prices. On one of her walks home, she experienced muscle cramping along with a fast heart rate, headache, dizziness and nausea. Mary sat down on the side of the road where she became confused and then passed out. Luckily, a bystander noticed and called 911. She was taken to a nearby hospital for treatment of a heat stroke.

Mary is not one real person, but the story and medical conditions are common.

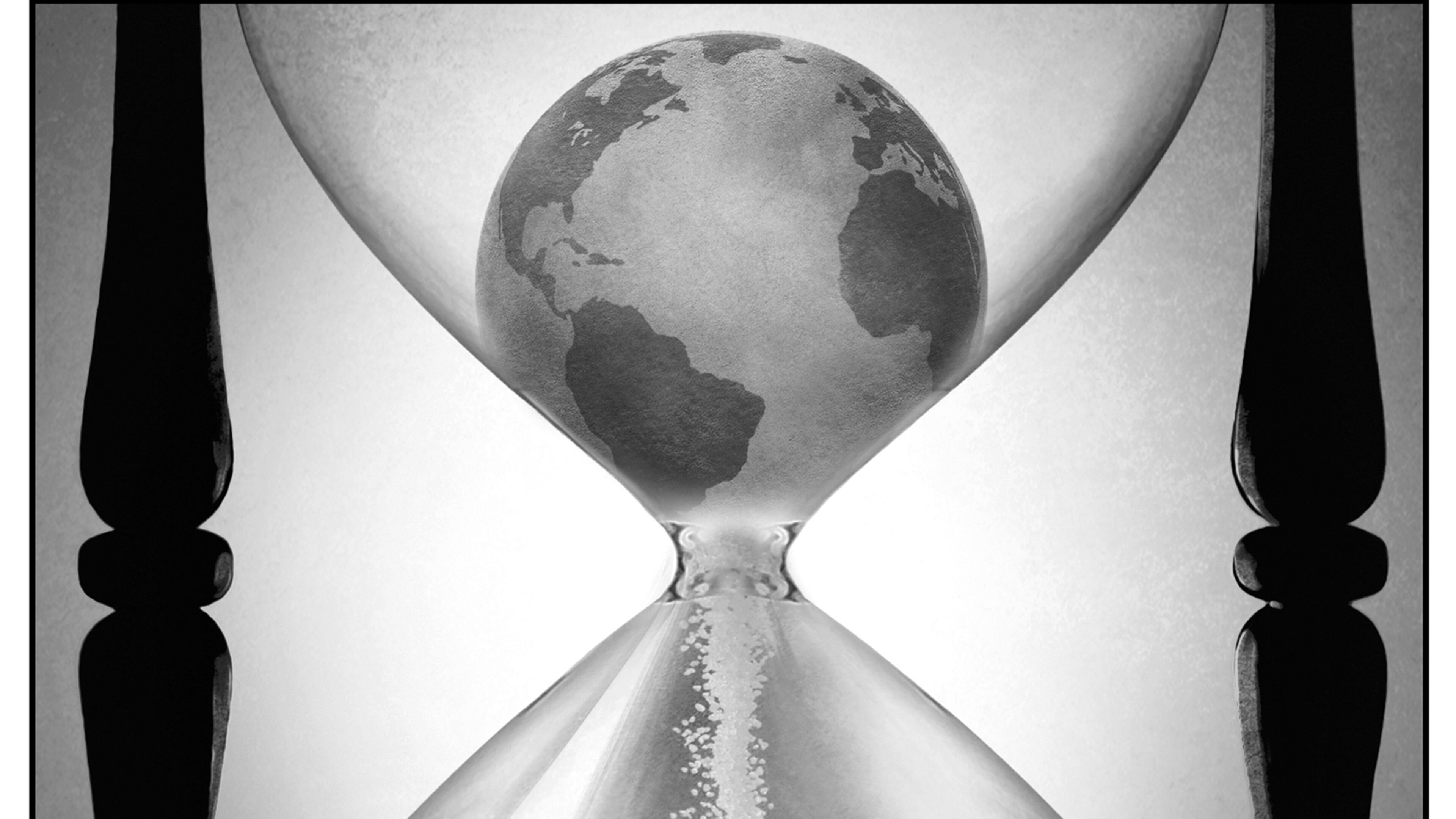

In this recent summer of record-setting heat, drought and epic storms, we are hearing a lot about climate change. At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic has raised new awareness of inequities in health. The above narrative shows how these issues are connected.

You may ask, doesn’t the weather affect all of us equally? Aren’t we all experiencing the same climate and environmental conditions? Why would one person be more affected than another?

Let’s unpack this.

First, it is clear that the climate is changing, and that the warming planet affects our health. Global temperatures have risen by about 2 degrees Fahrenheit since pre-industrial times, causing more extreme weather events, like flooding, droughts and wildfires. In the United States, last year was the second-worst on record for weather-related disasters, with 20 events resulting in the deaths of 688 people.

While climate disasters can affect anyone, low-income communities and people of color are hit first and worst. For example, Blacks or African Americans are already more likely to live in neighborhoods at risk of flooding and climate change is expected to make that worse.

Or consider extreme heat, the deadliest impact of climate change. Here in Georgia, we currently average about 20 dangerous heat days a year. But if climate change is not addressed, our state could see more than 90 dangerous heat days by 2050. In 2015, roughly 53 per 100,000 people in Georgia died of heat-related illness. If the number of dangerous heat days more than quadruples, we could also see a four-fold increase in deaths.

Here, too, Black and brown communities are hit hardest. The rate of heat-related deaths for Blacks is 150% to 200% greater than for whites in the U.S. Hispanic and/or Latinx persons are also more vulnerable, because they are more likely to work in high-risk industries like agriculture and construction. And low-income neighborhoods are actually hotter – by up to 20 degrees -- than wealthier parts of town, which usually have more cooling trees.

These changes in weather add to the collective stresses experienced by resource-poor communities. Such communities have struggled for years to access clean air, nutritious food, quality drinking water and safe shelter. Extreme weather events are layered on top of everyday insults like pollution, lack of green space, poor water quality and infectious disease that are harmful to our health. Climate change is an issue of health equity.

According to the CDC, health equity is “the state in which everyone has a fair and just opportunity to attain their highest level of health. Achieving this requires focused and ongoing societal efforts to address historical and contemporary injustices; overcome economic, social and other obstacles to health and healthcare; and eliminate preventable health disparities.”

The same inequities we see in healthcare, resulting from inequitable access to education and economic opportunity, are all exacerbated by climate change. Climate change and health equity go in hand in hand.

New federal legislation, the Inflation Reduction Act, may actually address some of these concerns. By promoting clean, renewable energy, the Act aims to reduce climate-changing carbon emissions and slow down planetary warming. The law offers incentives to buy electric vehicles and rooftop solar and will give a serious boost to Georgia’s growing solar energy industry.

By reducing emissions and air pollution, this federal legislation will mean cleaner air and better health for the people of Georgia. Still, we must make sure that those who are hit hardest by climate change see the benefits from the new law. Supporting local Georgia legislation that would enact an environmental justice task force or commission to consider and address the disproportionate impact of environmental-related policies on people of color and resource-poor families is a key step.

Climate change is here and now. And people face a double jeopardy from climate change and poor health. The good news is that climate solutions are also health solutions. Now, we must make sure those solutions reach those who need them most.

Tracey L. Henry, M.D., M.P.H., M.S. is a Climate and Health Equity Fellow for the Medical Society Consortium on Climate Change and an associate professor of medicine at Emory University. The views here are her own and do not represent Emory University.

More Stories

The Latest