Opinion: Art can let us learn and not repeat history’s pain

In the summer of 2008, my friend and colleague Doug Blackmon, then a reporter for The Wall Street Journal, sent me an early proof of a book he had tentatively titled, “Slavery by Another Name.” George Bush was president, a young senator from Illinois named Barack Obama was soon to clinch the Democratic nomination for president and the Great Recession was at our doorstep. Almost 15 years have passed since and, as the saying goes, a lot of water has gone under the bridge.

What has not changed is the importance of Blackmon’s Pulitzer Prize winning work and how it brought to light the uncomfortable truth that slavery in this country did not end with the Civil War. Through painstaking research and documentation, Blackmon was able to clearly demonstrate how hundreds of thousands of newly released men, women and children were systematically returned to a condition of ownership, or re-enslavement, with the help of state legislatures and law enforcement throughout the South.

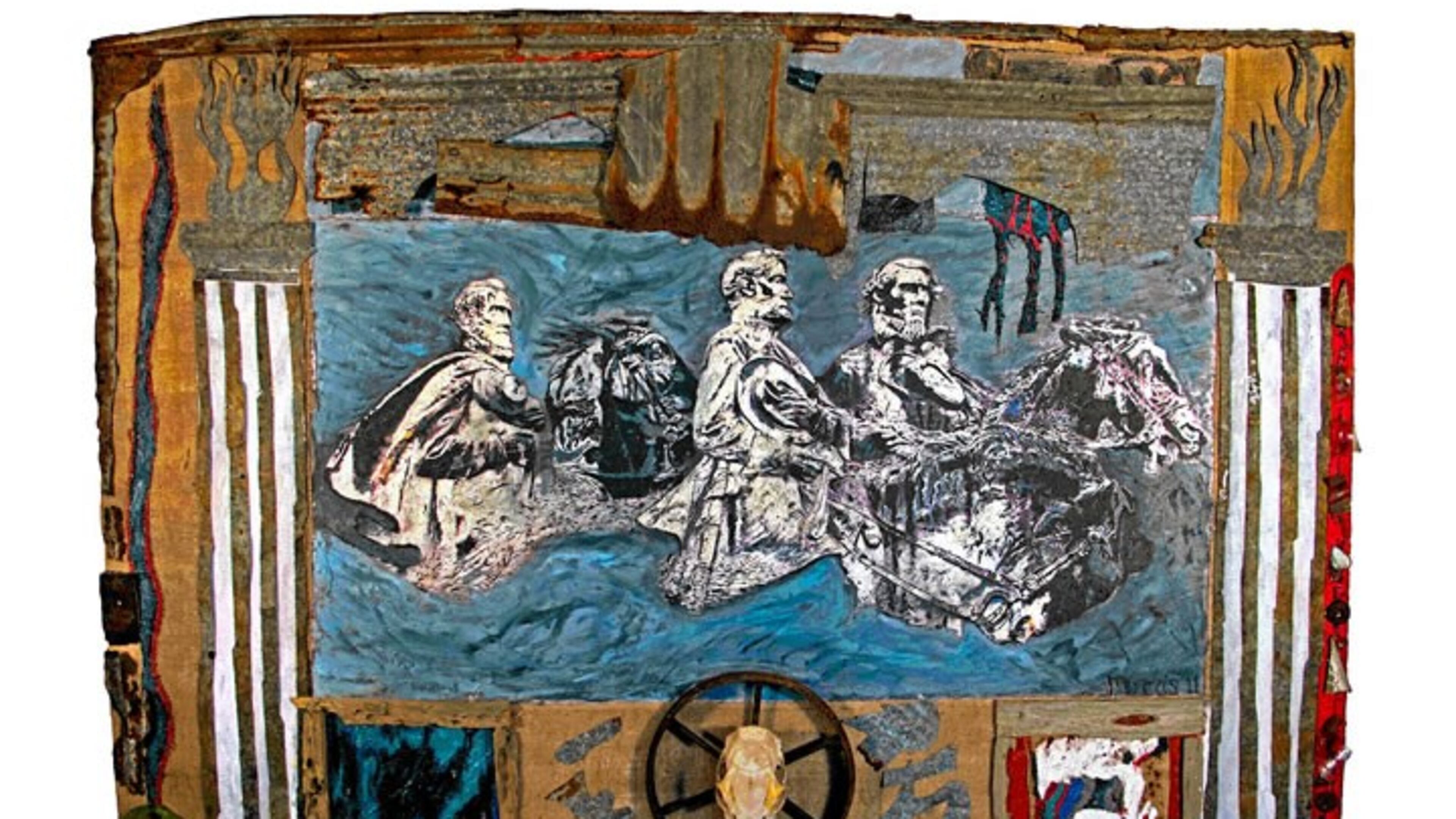

As an artist, writer and, at the time, executive at the Georgia Ports Authority, I found Blackmon’s words not only a wake up call, but a call to action. This story compelled me to set off on an odyssey across the Deep South in search of the artifacts, objects and records of this era to incorporate into my art. I became acquainted with southern ghost towns where, from the remains of dilapidated sharecropper shacks, I took pieces of broken tin that became the cotton stalks in my mixed media portrait of President Lincoln. I trolled the banks of the Savannah River at low tide and found shackles and chains that were said to have come from slave ships. These are now staked into the hardwood panel of a painting I call “Anonymous”.

The work was soon collected and curated in more than a dozen museums, galleries and libraries across this country, including the Telfair Museums, the Cincinnati Museum Center, the Rosa Parks Museum and the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Change. However, for the past seven years, the exhibition has sat in a warehouse with little to no interest from the outside world. I had begun to wonder if we were once again in a cycle of forgetting or otherwise abandoning our past. Would my art be forgotten and once again replaced by the convenient, sanctioned and made for Hollywood storyline that the Emancipation Proclamation ended slavery?

And then in January I received word from the Penn Center National Historic Landmark District, the former school for freed slaves which is now a cultural treasure, educational center and an African American legacy museum, that there was interest in another exhibition. They wanted to know if the work was still available?

“Hell yeah!” I said to myself and made arrangements to move the exhibition from mothballs in Atlanta to the storied walls of Penn Center on St. Helena Island in South Carolina.

It seems fitting that the work and, more importantly, the stories of the people who were harmed return now, in this time of eerie parallels between the eras. Over the past decade this country has witnessed an alarming rise in police brutality, voter suppression and the banning of books and cultural studies, all efforts that primarily impact and target African Americans. It seems the civil and human rights so many struggled to secure decades ago are in peril.

Is our country once again rescinding rights we consider inalienable?

The power of art, of visual language, is its ability to transmit not only information but also emotions that are both universal and deeply personal. My hope is that this work will be a reminder that, once upon a time, and time and time again, this country stole freedom away from Africans and then African Americans.

We should all feel called to prevent a revival of our worst sins.

Robert Morris’s exhibition, “Slavery by Another Name”, is open to the public in the York W. Bailey Museum at Penn Center, from now until June 1. An opening and talk by the artist will be March 18th at 6:30 p.m. in the museum. More information can be found at Penncenter.com.