It was two days before the judge was set to make a ruling in the King family’s copyright lawsuit over the “I Have a Dream” speech, and lawyer Joe Beck called the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s youngest son.

“Dex, we have a problem,” Joe Beck told Dexter King, who led the legal battle against CBS. A piece of recently unearthed evidence threatened to destroy the family’s case.

It was 1998, and the King family estate was suing CBS for using a large part of the speech in a documentary. The family argued CBS wrongfully used their property, while the network contended the speech belonged to the public.

Just before a federal judge was to rule on the case, the network’s lawyer called Beck to inform him he had found a copy of King’s 1963 speech. It had been distributed by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), King’s organization, as a fundraising tool. This threatened to upend the family’s argument it was copyrighted private intellectual property.

CBS told Beck the network would not ask for attorney’s fees if the family dismissed the suit. More importantly, CBS reasoned, the estate would not have a legal defeat on the record.

“If he lost, the family would have lost the rights (to the speech,)” said Beck. “If he lost, the whole revenue stream would have gone away.”

Carry on, Dexter told the lawyer.

Credit: File photo

Credit: File photo

(Ironically, the document that threatened to be a case-killer ended up being perhaps the family’s strongest piece of evidence.)

Beck, who is now retired, said he wanted to come forward to combat the widely shared image as Dexter as a combative, litigious person. King died last week of cancer at age 62.

Dexter was a lightning rod for critics, who included civil rights legends like Hosea Williams, Julian Bond and the Rev. Joe Lowery. They criticized the family for being overly protective of King’s legacy and for sometimes renting it out in advertisements. (I must admit that I, too, have joined them.)

“He wasn’t a mercenary person; he wasn’t avaricious,” Beck said. Because of his resolve, “You can’t put ‘I Have a Dream’ on a coffee cup.”

“I just want Dexter to get his credit; what he did in standing up to CBS was heroic,” said Beck. “Dexter took the lead on the case. It was him all the way.”

Dexter once explained his reasoning to The New York Times: “It has to do with the principle that if you make a dollar, I should make a dime.’’

He made lots of dimes.

The King family came in contact with Beck back in 1996 due to a favor his silk-stocking firm had long ago performed. Back in 1960, the Georgia Department of Revenue threatened to investigate both Ebenezer Baptist Church and its pastor, Martin Luther King Sr. It was a way to get to the son through the father.

Lawyer Louis Regenstein, then on the nameplate of the firm that is now Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton, put a stop to it. By 1996, Regenstein was dead, but partner Miles Alexander brought in Beck, an intellectual property whiz, to lead the case.

On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. delivered the rousing speech to 200,000 people from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. A month later, he copyrighted it. And days after that, King filed suit against a record company for selling recorded copies of his speech. He won.

But in 1998, King’s estate lost in a federal courtroom in Atlanta because King had not copyrighted it at the time of the speech. Judge William O’Kelley ruled that “Dr. King’s speech at the March almost epitomizes the definition of a general publication: it was made available to members of the public at large without regard to who they were or what they proposed to do with it.”

It was, he said, “one of the most public and most widely disseminated speeches in history, it could be the poster child for general publications.”

The family appealed to the federal appeals court in Atlanta. By then, Beck had made a discovery. The copy of the speech the SCLC distributed in 1963, the one found right before O’Kelley ruled against the Kings, had left out the good parts. Phrases like “I have a dream” and “let freedom ring,” were ad-libbed and were not in the planned speech.

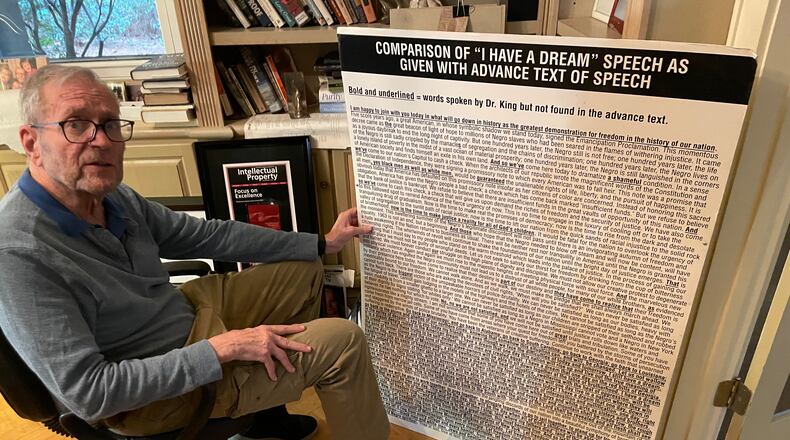

Beck printed up a large placard of the oration with the ad-libbed parts outlined in bold, probably a third of the speech. (He still has it in his home office.)

When Beck was to argue before the appellate judges, he asked that King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, accompany him into the courtroom with him instead of her son.

“Dexter, in some people’s minds, was not sympathetic,” Beck said. “She was.”

During his argument, Beck told the judges, “What King should have said was, ‘Free at last. Free at last. Thank God Almighty, I’m free at last. — All rights reserved.’”

The argument drew laughs in the courtroom, but Beck recalls, “I wanted to point out the absurdity to the court.”

Months later, the appeals court ruled in the Kings’ favor, kicking it back to the trial court.

“CBS did not want to try the case in Atlanta,” Beck recalled.

So they cut the King Center a check and the King heirs will own “I Have a Dream” until 2058.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured