In January, a state disciplinary panel determined that Georgia Appeals Court Judge Christian Coomer was anything but judicial material and should be removed from the bench.

Coomer, a former state legislator, had been accused of hoodwinking an elderly client right before he was appointed to the bench in 2018 and “illegally” using campaign funds for family vacations. A hearing panel of the Judicial Qualifications Commission (JQC) noted that Coomer used that client, who was pushing 80, as his “first and richest personal ATM.”

Ka-ching!

The future judge tapped his client for hundreds of thousands of dollars in “unsecured loans on unreasonable terms with meaningless maturity dates,” according to the JQC. One loan would have been paid off when the client hit 106 years of age.

On top of that, Coomer crafted a will for the man that designated himself as executor, trustee and beneficiary.

All of this should shock the conscience and came about because of a 2020 story by my colleague, Bill Rankin. The hearing panel, which spent seven days hearing Coomer’s alleged misdealings, determined he “should be removed from office so as to preserve (or at least begin to rebuild) the public’s confidence in the integrity of our judicial system.”

But the state Supreme Court said “Not so fast!” issuing the Monopoly equivalent of a Get Out of Jail Free card. Or more precisely, a Stay On The Bench card.

Credit: Natrice Miller/AJC

Credit: Natrice Miller/AJC

The high court this month noted their brother on the appeals court committed many of those acts before becoming Judge Coomer, so the JQC shouldn’t have been considering many of those allegations. “Pre-judicial” conduct, the court said, isn’t the JQC’s bailiwick.

Mind you, one of the first the rules in the JQC’s handbook simply — and clearly — states that “the commission has jurisdiction over judges regarding allegations that misconduct occurred before or during service as a judge.”

And that same Supreme Court, which oversees the JQC, approved those same rules just a few years ago. Also, that same Supreme Court was asked last year by Coomer to determine if any pre-judicial conduct should be considered. The high court punted on that question last March, allowing hundreds of hours of investigation and lawyering to occur, much of which was for naught.

The high court did say some of the charges against Coomer might stick and asked the three-member JQC panel to determine if Coomer acted in “bad faith” when he allegedly took advantage of his client and violated campaign finance laws.

The JQC panel must determine if Coomer purposely did wrong or if he just had a long, continued legal brain fart. The hearing panel clearly thinks the former, noting that an Air Force colonel, who was Coomer’s superior in the Judge Advocate General Corps, testified that Coomer was one sharpest lawyers she had dealt with.

Therefore, “the Hearing Panel is left to conclude that (Coomer), deemed to be in the top 1 percent of officers Colonel (Lorraine) Mink had ever met, knew exactly what he was doing when he convinced (the client) to loan his assetless and judgment-proof limited liability company hundreds of thousands of dollars on those unreasonable terms,” etcetera, etcetera.

So, perhaps all this was not a colossal waste of time. Maybe the investigation and JQC trial brought into clear focus what one of Georgia’s top judges was up to months before he donned the robes.

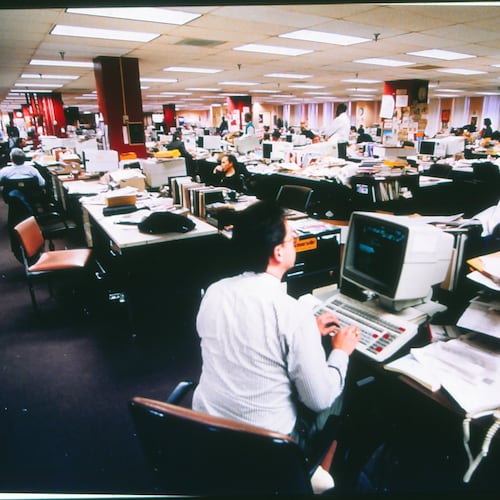

Credit: Bob Andres

Credit: Bob Andres

I called Dennis Cathey, one of Coomer’s lawyers during this long, incessant process. Did I mention that Coomer has been suspended (with pay) for more than two years? His absence has left a hole in the busy Appeals Court and a divot in the Georgia treasury to the tune of $400,000.

“We’re seeking to have Chris reinstated to the bench,” Cathey said, adding the ultimate decision is up to the state Supreme Court.

During the JQC hearing, Cathey admitted his client made some mistakes and maybe should be reprimanded, but certainly not receive a career “death penalty.”

“He made restitution. He admitted it. He expressed remorse. He cooperated fully,” Cathey said. “That is not conduct that would result in disbarment as a lawyer. If it doesn’t carry disbarment as a lawyer, it shouldn’t carry ‘lose your robe’ as a judge. It just shouldn’t.”

The hearing panel didn’t ultimately see it that way, saying Coomer should get defrocked because of his “steadily recurring abuse of positions of trust to his own benefit and his lack of remorse for his conduct.”

Coomer did repay the loans, but only after his client sued him. So, it’s like paying for a candy bar only after the shopkeeper catches you.

Lester Tate, a former JQC member who is representing a judge also charged with pre-judicial conduct, certainly agrees with that part of the Supreme Court’s ruling.

But Coomer is by no means out of the woods, he said.

“I defend a lot of lawyers and there are clearly issues here that are prohibited by the Georgia Profession Rules of Conduct,” Tate said. “If he was prosecuted (by) the (State) Bar, it could cost him his license and then he could not be a judge.”

The state bar confirmed it is investigating him.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured