In the months following the end of the Civil War, two units of black Union soldiers were assigned to the burned-out husk of Atlanta to keep the strained peace.

Former slaves who had toiled in nearby fields, and who were perhaps bought and sold on the slave market at what is currently the site of the Five Points MARTA station, now carried guns and wore the blue suits with shiny brass buttons of the victorious United States Army.

Several miles away, “Ten Cent” Bill Yopp was trying to find his footing. Born a slave, he spent the war as a Confederate drummer, shining boots for a dime and tending to the wounds of his master, Capt. Thomas McCall Yopp.

After the war, “Ten Cent” raised money for Confederate veterans and stayed by his former master’s side as he lived out his final years in the Confederate Soldiers’ Home in Atlanta. When he died in 1933, “Ten Cent” became the first and only African-American to lie in the Confederate Cemetery in Marietta.

These are stories that will be sifted through as officials at Stone Mountain begin work on one of their most ambitious projects ever — creating a permanent museum exhibit about the role of blacks in the Civil War.

Earlier this month, the board of the Stone Mountain Memorial Association voted unanimously to move forward on the planning of the project.

“I think it is a great idea,” said board chairwoman Carolyn Meadows. “We thought that it was appropriate to honor African-Americans who fought, regardless of which side they were on.”

Stone Mountain is one of Georgia’s leading tourist attractions, getting about 4 million visitors a year.

Moving forward on a proposed museum meant slowing down a bigger plan to diversify the Stone Mountain story by building a memorial to Martin Luther King Jr. on top of the mountain, mere feet away from where the Ku Klux Klan re-established itself a century ago on Nov. 25, 1915.

Stone Mountain Memorial Association CEO Bill Stephens said the museum is now the priority. If it is indeed built, it would be only the second museum of its kind in the United States.

In 2000, Frank Smith, a Newnan native and a longtime Washington, D.C., city councilman, opened the African American Civil War Memorial and Museum near Howard University, attracting about 150,000 people annually.

“I challenge my museum friends in Atlanta to get the story straight,” Smith said. “But I welcome them. We are underrepresented in the museum arena. You can never have enough museums telling our stories.”

Which stories to tell will be the challenge for the museum’s curators. As convoluted as Civil War history can be, the story of the black soldier is even more complicated.

Take this argument from several weeks ago: A group of Confederate flag supporters marched on Stone Mountain to protest plans for the King memorial, arguing that because the civil rights leader had no involvement in the Civil War, he had no place on Stone Mountain, which is a Confederate memorial.

Instead, they said, they would support a monument for a black Confederate soldier.

But they couldn’t name one. And for good reason. There were none.

THE CONFEDERACY

According to service records kept by the National Park Service, of the 209,145 black soldiers listed as having served in the Civil War, 209,145 fought for the Union.

Despite arguments to the contrary, there is no documented evidence that blacks — former slaves — fought on the side of the Confederacy.

Boston-based historian Kevin Levin said he has been working on his upcoming book, “Searching for Black Confederate Soldiers,” for eight years and has yet to find one.

After the Civil War “it would have been hard for any Confederate to acknowledge knowing or seeing any black soldiers,” Levin said. “The myth of the black Confederate soldier is a recent myth that started in the late 1970s.”

At that time, as America was coming out of Vietnam and the end of the Civil War was more than a century removed, memories of it began to shift toward an increased interest in emancipation and the service of blacks in the Union.

‘They were not soldiers’

That interest intensified in 1989 when the movie “Glory,” based on the book “One Gallant Rush: Robert Gould Shaw and His Brave Black Regiment,” was released, telling the story of the first all-black regiment in the Union Army, the 54th Massachusetts Regiment.

“So there was a push to counter that by looking for their own Confederate soldiers,” Levin said. “If you can find black men, you can defuse the talk of emancipation. … It is a myth that lives on the Internet, but there is no reputable scholar who supports this myth.”

Several Confederacy-themed websites report that there were indeed blacks who voluntarily fought for the South, including “Ten Cent” Bill Yopp.

But the true story of “Ten Cent” — who Levin said is on a short list of former servants who have been transformed into loyal Confederates — is more in line with what the black role was for the Confederacy.

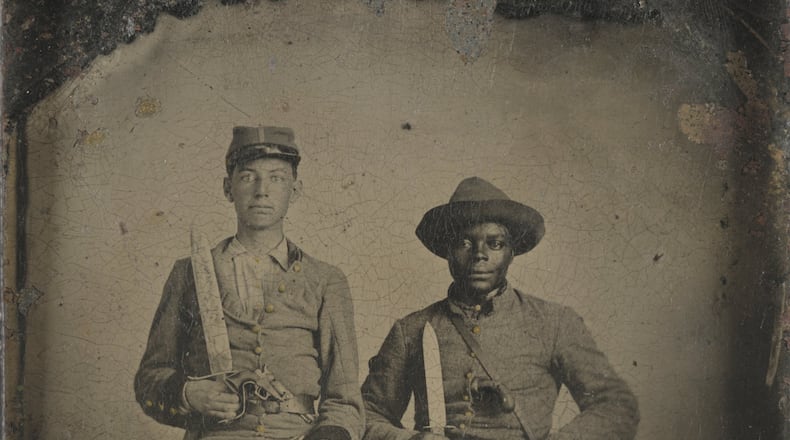

“The Confederate government used slaves to free up as many white men to fight on the lines,” Levin said. “Many of these (black) men were in uniform, so when you see photos many confuse them as evidence that they were soldiers. But they were not.”

‘A white man’s war’

Historian Michael Thurmond said as many as 1 million slaves worked in some way for the Confederacy, “working in the back as cooks, digging trenches, making uniforms and supporting troops.”

“But that didn’t make them Confederate soldiers. It made them slaves serving their masters,” said Thurmond, Georgia’s former labor secretary and DeKalb County’s former interim schools superintendent.

“A soldier is someone who volunteers. A slave cannot volunteer. … The Confederacy did not want to arm slaves,” Thurmond said.

Neither did the Union, at least early on. When the war started, both sides prohibited blacks from serving, which prompted President Abraham Lincoln to call it “a white man’s war.”

‘They picked slavery’

Gen. Robert E. Lee, whose image is carved on Stone Mountain, was actually in support of arming slaves in exchange for their freedom after the war. But the Confederate government, at the urging of its president, Jefferson Davis, who is also carved on Stone Mountain, voted it down.

“By November of 1864, the Confederacy was faced with the decision. ‘Do we want to win the war or protect slavery,’” Thurmond said. “They picked slavery.”

It wasn’t until April 1865 that the Confederate Congress voted to arm blacks.

It was too late.

THE UNION

After Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863, some 200,000 blacks — 90 percent of them former slaves from Confederate states — had already turned the tide of the war by taking up arms for the Union.

The Confederates “did set up recruiting stations in Columbus and Macon and some blacks were mustered in, but they never served,” Thurmond said. “The war ended before they could be deployed. It was over and there is no record of this. No official records show black soldiers in the Confederacy.”

The record is clearer on the North. With the Emancipation Proclamation, former and runaway slaves flooded the North. By March of 1863, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment had been established.

Their most famous battle occurred on July 18, 1863, when the regiment led the assault on Fort Wagner near Charleston, S.C. Of the 600 men who charged the fort, 272 were killed, wounded or captured, the highest number of casualties the 54th took in a single engagement.

‘Law and order’

“It is generally thought that Lincoln gave them freedom, but they earned it,” Thurmond said of former slaves.

After the war on July 15, 1865, two units of the United States Colored Infantry were formed in Atlanta: the 136th Regiment and the 138th Regiment.

“When (Gen. William T.) Sherman is going through the South, as he took these territories, he had to leave some soldiers on the ground to occupy, patrol and do law and order,” said Smith, who opened the African American Civil War Museum in Washington. “So they recruited these two regiments down in Atlanta.”

Smith said 3,486 men, most of whom were Georgians, were recruited into the two regiments.

Both units were mustered out of Atlanta in early 1866.

‘Distrust or hostility’

Atlanta locals, still loyal to the Confederacy, were not pleased by the sight of blacks in blue uniforms.

Thurmond, in his book “Freedom: Georgia’s Antislavery Heritage 1733-1865,” wrote about that tension, based on accounts and diaries:

“Garrisons where colored troops were established were centers for disturbance. Hotheaded young Southern men would not brook for the lording insolence of blacks in brass buttons. And Negro soldiers everywhere had a bad influence on the freedmen of the neighborhood, encouraging them to idleness and arousing in them a feeling of distrust or hostility to their white employers.”

'Something new'

It’s all rich material to sort through for the Stone Mountain museum project.

Stephens, the Stone Mountain Memorial Association CEO, said he will spend the next few months talking to opinion leaders and getting legal and financial evaluations on how to make the museum a reality. The goal is to have something in place by 2016.

“I hope it tells the story of how the Civil War impacted everybody, black and white, North and South,” Stephens said. “And hopefully, people can learn something new.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured