SALT LAKE CITY -- Here in the capital of Mormon country, a downtown street is being renamed for Harvey Milk, the San Francisco politician and gay activist shot to death in 1978.

The street-naming comes as battles over gay rights have reached a fever pitch: North Carolina is defying the federal government over transgender bathrooms, Mississippi is being sued over its new "religious liberty" law, and Alabama's chief justice has been suspended for blocking same-sex marriages.

But in this red, red state, gay politicians and activists say the street-naming speaks to their ability to work with the church, an ultra-conservative Republican Legislature and a community that's two-thirds Mormon.

"The issues that are dividing America are kind of elevated here," said Troy Williams, executive director of Equality Utah. "If we can learn to solve them in Utah, there's hope for the nation."

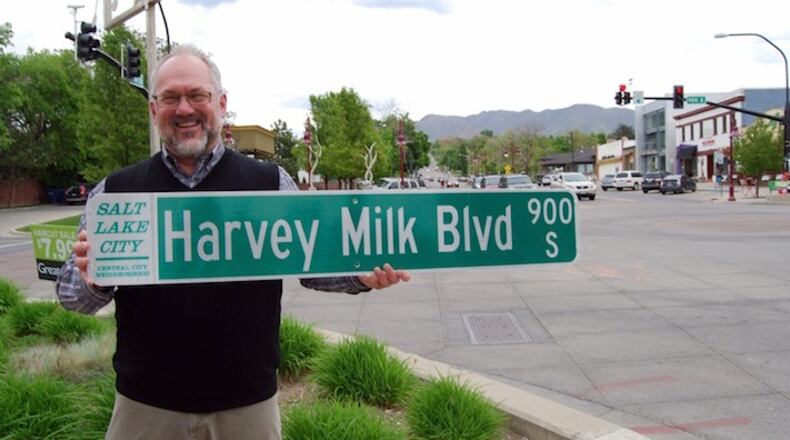

The push to turn a 20-block stretch of 900 South St. into Harvey Milk Boulevard began with Williams, whose office wall downtown is covered with portraits of the gay icon, including a Milk poster urging people to join "the gay liberation front." On the opposite wall is a framed photo of Republican Gov. Gary R. Herbert signing a nondiscrimination bill last year that protected gays and lesbians – the same governor whose office Williams and other protesters were arrested for blocking two years ago with a sit-in.

Williams, who was raised Mormon, said he and other activists made inroads with state lawmakers by first reaching out to the church.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has fought same-sex marriage, considers homosexuality a sin and announced last fall that children of same-sex couples must "disavow" their parents' relationships and receive church leaders' approval to be baptized and participate in church functions. But church officials also supported the nondiscrimination law.

"The church believes in a 'fairness for all' approach on the issues of housing and employment, which balance LGBT rights and religious rights and which were at the heart of the nondiscrimination legislation," said church spokesman Eric Hawkins.

Williams noted that a law similar to the one adopted in Mississippi was proposed in the Utah Legislature but never made it to a vote. Last month, when the Milk street name change came up for a vote before the City Council, all seven members approved it, including the chair and three other Mormons.

"Utah is a red state, but not a redneck state," Williams said. "There's a willingness to collaborate."

Now he and others are walking the fine line between advocacy and tolerance as they push for transgender rights in health care and public accommodations (including bathrooms, the issue that sparked outcry in North Carolina). Harvey Milk Boulevard, Williams said, will be both sanctuary and rallying point.

"It's about having a presence. This was Harvey's whole thing: come out. Because if you come out, they're going to have a harder time taking away your rights," he said.

A few residents opposed the name change at a council meeting before the vote. But Stan Penfold, the state's first openly gay councilman, whose district includes the Mormon Church headquarters, pointed out that church leaders did not fight it.

"If we were looking at a liquor-law change, we'd hear all about it," said Penfold, who was raised Mormon. "Part of that comes from the relationships that were forged when the nondiscrimination law passed."

But it's also the attitude of conservative Utahns, whom Penfold described as "a really tolerant community, even though they disapprove."

Salt Lake City, like other blue islands in red states, has been a beacon for gays and lesbians for generations. City voters have not elected a Republican or practicing Mormon mayor in 33 years, and the recent infusion of young tech workers has made the city even more progressive.

Last year, another openly gay city councilman joined Penfold and successfully sued to overturn the state's same-sex marriage ban (he's opening a deli on Harvey Milk Boulevard). In January, the city elected a lesbian mayor and last month banned city-sponsored travel to North Carolina and Mississippi because of their laws that critics view as discrimination against gays.

Salt Lake City has the seventh-most gay residents per capita in the U.S. (Los Angeles has the eighth-most), according to Gallup.

The heart of the city's gay community has long been the maple-lined street about nine blocks away that's being renamed for Milk, particularly the festive, pedestrian-friendly area known as 9th & 9th. When Equality Utah staged an online fundraising campaign to pay for the new street signs, the $8,000 was raised quickly.

Some residents objected to the street renaming, and their concerns foreshadow challenges gay activists face as they push for greater protections.

Marla Foote has lived on the street for 17 years, and spoke against the name change before the City Council. She came to the screen door of her brick tract house in a purple flowered dress, gray hair swept up into a bun, and pointed to the homes of other neighbors who agreed.

"We see absolutely no reason to rename it for someone who has no ties here," she said. "He's never even been to Utah as far as we can tell. He's a California person."

Foote, 63, a UnitedHealthcare analyst, acknowledged that other streets here have been renamed for nonnative civil rights leaders: the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Cesar Chavez.

But that wasn't the only reason Foote opposed the name change. She said 9th & 9th has evolved into "Little Castro," referring to San Francisco's Castro District – one of the nation's first gay enclaves.

She pointed to the nearly identical red brick house next door, where a gay couple live. They share dinners, and she attended their wedding on the front patio. Last year, Foote – a registered independent _ wrote to state lawmakers to support the nondiscrimination law, she said.

But the street renaming put her on the defensive. Now she thinks Utah might need a religious liberty law.

"They do have a right to have the same jobs, the same pay for the same jobs. I'm fine with that. As long as they're not shoving my face in it," she said. "I want my rights protected, too."

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured