To find out more about how lethal injection works in Georgia and to watch an animation of how an execution by lethal injection is performed, visit myajc.com http://specialprojects.myajc.com/lethal-injection/

THE GEORGIA WOMAN ON DEATH ROW

» Kelly Gissendaner was convicted in the 1997 murder of her husband and was sentenced to death in 1998.

» She was scheduled to die by lethal injection twice in 2015. She would have been the first woman executed in Georgia in 70 years. But the first scheduled execution was postponed because of inclement weather, and a second postponement occurred in March because the drug, pentobarbital, appeared lumpy rather than clear.

» Attorneys for the mother of three sued in federal court, saying the delayed executions violated the Eighth Amendment guarantee against cruel and unusual punishment.

» The state determined the drug was lumpy because it had been stored at too cool a temperature.

» Gissendaner’s attorneys have asked for further analysis of the drug to determine its exact compounds. The case is still in federal court.

States may use a controversial sedative to perform executions, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a 5 to 4 decision on Monday, saying use of the drug did not constitute cruel and unusual punishment.

But two of the court’s justices said in their dissents that the real issue isn’t whether use of the sedative violates the Eighth Amendment. Instead, they said, it’s a question of the constitutionality of the death penalty itself.

Although the case decided Monday, Glossip v. Gross, involved three Oklahoma death row inmates, the ruling could have implications for Georgia. Earlier this year, Georgia was set to execute its first woman in 70 years. But Kelly Gissendaner's execution was put on hold indefinitely after the drug that was going to be used to kill her developed abnormal clots. A current lawsuit on her behalf in federal court alleges that episode amounted to cruel and unusual punishment.

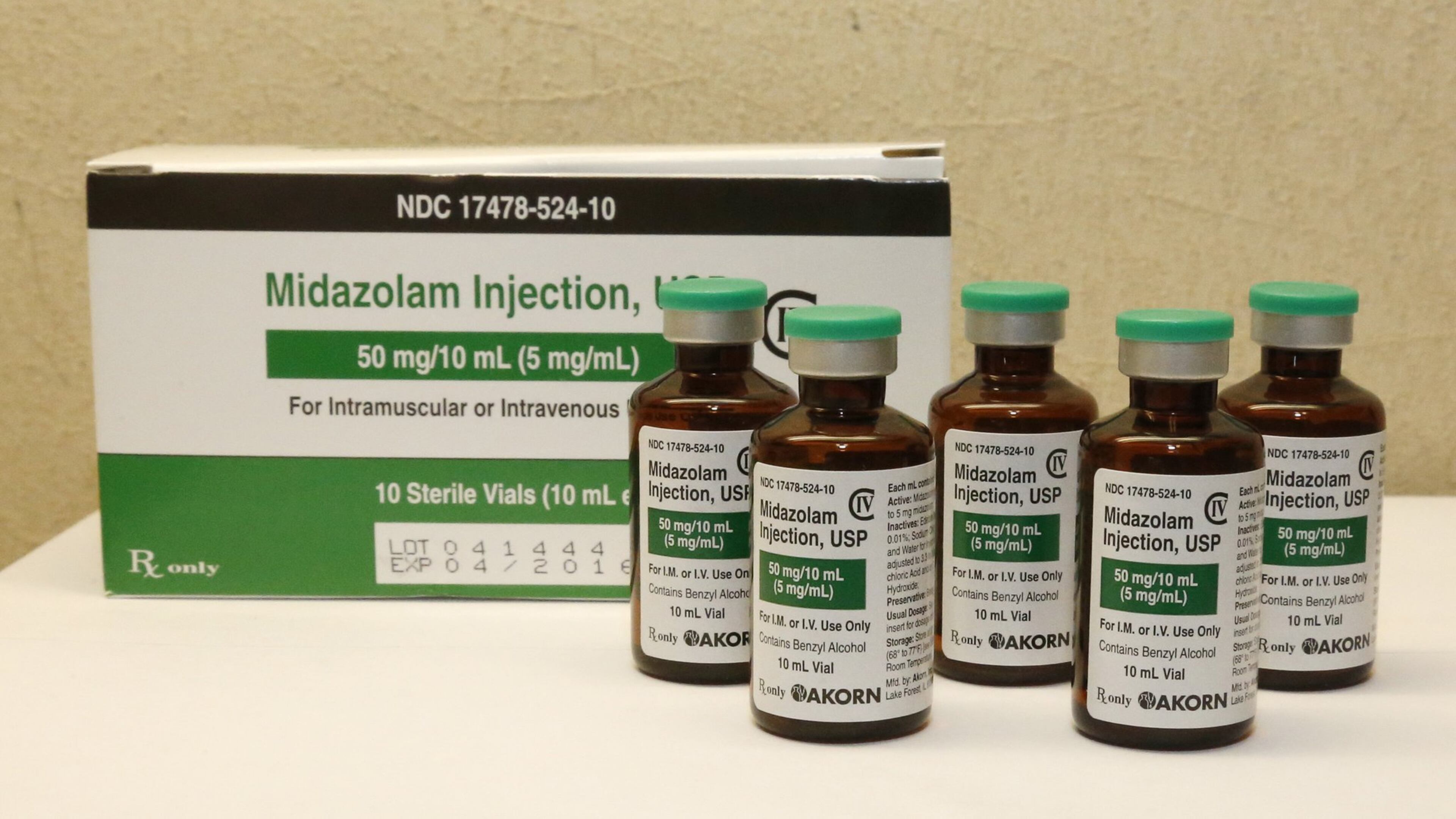

In Gissendaner's case the drug was pentobarbital. In Glossip, the argument centered around the sedative midazolam and its use in a three-drug protocol used to kill prisoners.

Midazolam is supposed to put an inmate into a medical coma so he or she won’t feel the effects of two subsequent drugs used to complete an execution. The second drug paralyzes all voluntary muscles, including the lungs, and the third drug stops the heart. Without proper sedation, a person can feel the effects of the other drugs.

Midazolam was used in three so-called botched executions in Oklahoma, Ohio and Arizona last year, and inmate deaths that should have occurred in 10 minutes took up to two hours. The condemned men writhed, gasped or tried to cry out as the drugs took hold. In Glossip, the petitioners argued those executions were evidence the midazolam was not suitable for lethal injections.

Arguments ‘all lack merit’

Writing for the conservative majority, Justice Samuel Alito said the petitioners’ “arguments about midazolam all lack merit.”

“Petitioners have not proved that any risk posed by midazolam is substantial when compared to known and available alternative methods of execution,” Alito wrote. Citing previous case law, Alito said that the burden of finding an alternative to midazolam — or any other drug for execution — rested with the inmate and his or her defense team, not the state.

Alito went on to say that the majority wasn’t convinced that the difficulties with the executions in Oklahoma and Arizona were related to midazolam.

"Twelve other executions have been conducted using the three-drug protocol at issue here, and those appear to have been conducted without any significant problems," Alito wrote. Therefore the executions of Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma and Joseph Wood in Arizona "have little probative value for present purposes."

Lockett clenched his teeth and braced against the gurney so violently after being given the drug that Oklahoma officials tried to stop, then restart, the execution. It took 43 minutes for him to die.

Two dissents and a response

In a stinging dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor said, “Under the court’s new rule, it would not matter whether the state intended to use midazolam, or instead to have petitioners drawn and quartered, slowly tortured to death, or actually burned at the stake.”

Alito responded to her dissent, saying the majority decision did not amount to torture, “and the principal’s dissent’s resort to this outlandish rhetoric reveals the weakness of its legal arguments.”

Justice Stephen Breyer, however, said in a separate dissent joined by Justice Ruth Beder Ginsburg that it was not the method that should be considered, but whether state-sponsored executions should be done at all. Breyer said cases over the last 40 years have proved the death penalty “is imposed arbitrarily, without the ‘reasonable consistency’ legally necessary to reconcile its use with the Constitution’s commands.”

Twenty years on the court “lead me to believe the that death penalty, in and of itself, now likely constitutes a legally prohibited, ‘cruel and unusual punishment,” Breyer wrote.

Implications for Georgia

On its face it would seem the Glossip v. Gross decision does not directly affect lethal injection in Georgia.

Three years ago, Georgia abandoned the three-drug protocol at issue in Glossip. It did so because the U.S. manufacturer of one of the drugs — sodium thiopental — stopped making it after a campaign by death penalty opponents to cease its sale for executions.

Georgia then switched to a one-drug execution method using the barbiturate pentobarbital. But opponents put pressure on the U.S. distributor of that drug to stop allowing its use for executions.

As the drugs have become scarce, states have had to come up with new combinations of execution drugs, as was the case in Oklahoma, Ohio and Arizona. They’ve also had to find alternative sources, including compounding pharmacies, to make the drugs. How those drugs are made and who administers them is often protected by state shield laws, like the one Georgia passed in 2013. Without them, sourcing the drugs and finding doctors to assist or observe executions would be too difficult, corrections officials say.

Attorneys for death row inmates argue that without knowing how the drugs are made, the compounds have the potential to inflict great pain and can lead to a botched execution.

How much will it hurt?

The question of pain was central to the Glossip case, and that’s where the Supreme Court’s ruling has the potential to impact Georgia and other states that use compounding pharmacies to make drugs for executions.

Inmates' legal teams can potentially hold up an execution in the courts for weeks, if not months, arguing about the composition of a drug and whether it will lead to an excruciating death. Earlier this year, Gissendaner's execution was called off hours after it was scheduled because the pentobarbital had discolored clumps in it. Pentobarbital is supposed to be clear.

Georgia conducted its own investigation of the chemicals and said the odd texture developed because the drug had been stored at too low a temperature. In a lawsuit now making its way through federal court, Gissendaner’s lawyers say she was subjected to cruel and unusual punishment because the lumpy drug caused a delay in her execution. They want further analysis of the pentobarbital because they are unsure of the drug’s composition and whether it would cause pain.

A ploy to end lethal injections?

When Glossip was argued in April, the court’s conservative justices suggested arguments over the efficacy of the drugs is a tactic designed to dry up the supply of any pharmaceutical that could be used to kill an inmate, effectively ending lethal injections.

“I mean, let’s be honest about what’s going on here,” said Justice Alito to Robin Konrad, who was representing the Oklahoma death-row inmate. “Is it appropriate for the judiciary to countenance what amounts to a guerrilla war against the death penalty, which consists of efforts to make it impossible for the states to obtain drugs that could be used to carry out capital punishment with little, if any, pain? And so the states are reduced to using drugs like this one (midazolam), which give rise to the disputes about whether, in fact, every possibility of pain is eliminated.”

Georgia has relied on undisclosed compounding pharmacies to make pentobarbital. But though they are licensed by the state, compounding pharmacies do not make drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The issue of pain was central to the last lethal injection case the court heard, in 2008, Baze v. Rees. In that case, the court said there was always the risk of pain in “even the most humane execution method,” but that the Constitution “does not demand the avoidance of all risk and pain.” So, the court said, a measure of pain might not be enough to violate the Eighth Amendment protection against cruel and unusual punishment.