Fifty-six years after dozens of African American girls were imprisoned in Lee County for taking part in a civil rights protest, a historical marker will finally memorialize the event.

The marker, which will be installed Sept. 27 outside the old Leesburg stockade in southwest Georgia, will be part of the Georgia Historical Society’s Civil Rights Trail.

In July 1963, the civil rights movement took hold in Sumter County. In Americus, the county seat, African American youth made up the bulk of the protesters. During a series of marches and protests against the town's segregated movie theater, hundreds of young people were rounded up and arrested. The majority of them were never formally charged or brought before a judge, but they were jailed by local authorities for weeks at a time. Their parents weren't initially told where they were being held.

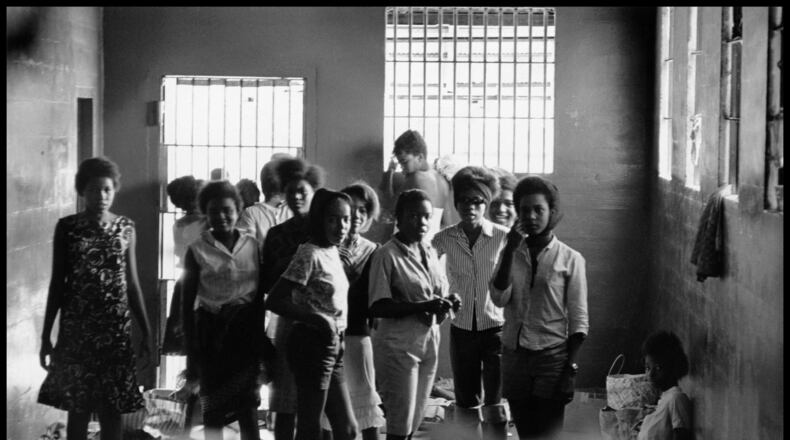

Dozens of girls were taken to the stockade, a forlorn and remote building in Lee County. The building had no working toilet or fans and not enough beds. The girls were released after Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee photographer Danny Lyon secretly took pictures of them in jail and the photos were published in African American newspapers.

“The charge was made that the children were used as pawns, but civil rights leaders understood that locking up underage girls would shock the conscience of the nation,” said Stan Deaton, senior historian with the society.

As the girls became women, they told their story, which has been the subject of books, documentaries and magazine articles. Some of the them will attend the marker installation in front of the stockade which still stands.

About the Author

The Latest

Featured