When Matt Coley left his job on Capitol Hill a few years back, he decided to return to his family’s decidedly un-Washington business of growing cotton and peanuts.

He now tends to roughly 3,400 acres about 45 minutes south of Bonaire, the Middle Georgia town called home by the soon-to-be most powerful man in agriculture.

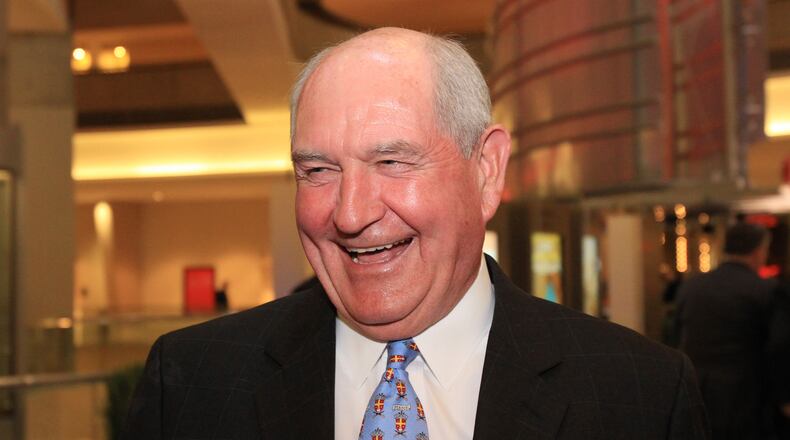

That man is former Gov. Sonny Perdue, whom the Senate is expected to confirm as the 31st secretary of agriculture on Monday.

Perdue’s ascent to the Cabinet thrills Coley.

“He knows the struggles that farmers deal with on a day-to-day basis,” Coley said of Perdue. “Having that perspective in D.C. would certainly be a benefit when decisions are having to be made.”

President Donald Trump’s selection of Perdue to be the country’s top agriculture official back in January drew notable approval from the often factionalized ag industry and senators from both parties — and only token opposition.

The enthusiasm has been particularly pronounced in Georgia. In the former veterinarian and agribusiness owner, many see a knowledgeable stakeholder who will not only stick up for rural America in a White House filled with city dwellers, but return their calls and support some of the state’s top crops.

“When he was governor, he spent a large amount of his time traveling the world selling Georgia and selling Georgia ag products,” said Georgia Chamber of Commerce President Chris Clark, who served as natural resources commissioner in the Perdue administration.

Perdue’s expected confirmation, he said, gives “us, our farmers, our forestry an opportunity to grow our brand.”

But what it means for Georgia is a little more muddled.

It would undoubtedly mean a friendly face in Washington’s upper echelons, as well as a more direct line to the White House for many of Perdue’s Georgia allies. And while drafting policy exclusively favoring Georgia would be met with suspicion, Perdue will be stepping into a powerful bully pulpit.

Of immediate concern, farmers in the state are looking for the U.S. Department of Agriculture to make low-interest emergency loans to Georgia’s blueberry farmers after freezing temperatures killed millions of dollars worth of crops in March.

Not everyone in the state thinks Perdue’s ascension would benefit Georgia.

Neill Herring, a lobbyist for the Georgia branch of the Sierra Club, worries that Perdue’s focus on agriculture and farming will come at the expense of conservation programs.

“The USDA can be such a great doer of good and has been in historic times,” he said. “But the focus now on commodity production, the concentration and accumulation of resources is such that it’s really hard to be optimistic that they’re going to be good for the planet or the climate or the impact of agriculture in communities.”

Herring said he's concerned that Perdue will go along with the ag industry and the Trump administration's opposition to a divisive Obama-era EPA regulation governing waterways and wetlands, and be inclined to trim funding for food stamps and other nutrition programs.

Money talks

Cabinet secretaries wield their influence in many ways, but perhaps the strongest tool in their arsenal is money.

Congress holds the federal purse strings, but past agriculture secretaries have found ways to direct money toward favored programs and causes.

Perdue adroitly moved money around in state government to meet financial needs, and he could conceivably undertake similar actions in his new job, said Ferd Hoefner, a senior strategic adviser at the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition.

“There are some kind of unique funding tools at their disposal,” said Hoefner. “Because the farm economy is in a bad state of affairs right now, there could easily be members of Congress looking to the secretary to make creative use of some of those funding mechanisms that they have.”

There are other regulatory levers that agriculture secretaries control that will likely put Perdue in the spotlight, particularly when it comes to commodities such as cotton.

Grappling with low demand and foreign competition that have tamped down prices, cotton growers asked President Barack Obama's agriculture chief Tom Vilsack to change the federal definition of oilseed in order to include cottonseed,a move they said would give them access to more government money. Vilsack denied their request, saying he did not have the authority to do so.

“That will be a decision that Sonny Perdue will have presumably early on as to whether he will make that move that Secretary Vilsack didn’t,” said Hoefner.

Bully pulpit

A key component of the job is working with agriculture ministers across the world, said Mike Johanns, who served as agriculture secretary during the George W. Bush administration.

He said Perdue will be on the front lines if another country threatens to close its borders or institute new tariffs on certain exports, moves that could have major implications on Georgia crops.

Poultry, by far the state's largest commodity, was adversely impacted when South Africa imposed tariffs on imported chicken, a decision that was eventually reversed in 2015.

Trade disputes “may be the first thing on his agenda most days when he comes into the office — some country threatening to close their border or whatever,” Johanns said. “Sonny really will be a key player in that.”

Conversely, Perdue also will have a key role negotiating agricultural trade with countries. Clark of the Georgia Chamber believes that could mean more opportunities to push Georgia crops in parts of the Middle East, Africa and Asia. There’s particular optimism surrounding the prospect of opening up trade with Cuba.

There's also a broader desire in the country's agriculture groups that Perdue encourage Trump — who campaigned on a hard-line immigration and economically protectionist ticket — to support policies that defend ag exports and the special class of immigration visas farmers rely on for seasonal workers. Past delays in approving paperwork at the Labor Department have already led to revenue losses for Georgia farmers, and Trump has proposed slashing the agency's budget in the upcoming fiscal year.

“We have to have that labor if we want to continue to eat what we grow in this country,” Clark said. “Having an advocate who can explain that impact and why it’s important I think is going to be very, very important for farmers in this state.”

Farm bill

Part of the broader reason why Perdue’s nomination was met with such enthusiasm in Georgia and the South is regional.

Perdue would be the first ever agriculture head to hail from Georgia, and the first southerner in more than two decades.

“The voices of Southeastern agriculture are going to be heard and that’s exciting,” said Georgia Agriculture Commissioner Gary Black.

Politicians have long battled over which crops — pecans and rice from the South, produce from California and corn and soybeans from the Midwest, to name a few — should get larger shares of federal subsidies.

Georgia farmers are hoping that having Perdue in agriculture’s top job will provide extra negotiating power as Congress begins discussions surrounding the new farm bill, the massive piece of legislation that will set agriculture, nutrition and conservation policies for the next five years.

The 2018 bill will determine the level of federal subsidies specific crops receives, a critically important issue for Georgia farmers and their economic livelihoods.

That legislation will also set the funding formula for food stamps, which are used by roughly 1.7 million Georgians, or 17 percent of the state, according to the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

The U.S. House and Senate Agriculture committees have jurisdiction over the bill, but Perdue will have major negotiating power as Trump’s top agent. Georgians are optimistic they’ve been able to stack the deck in their favor: four lawmakers from the state sit on the two committees, and former Georgia Farm Bureau chief Zippy Duvall now leads the powerful American Farm Bureau.

“The stars are aligning in some respect,” said Adam Rabinowitz, a professor of agricultural and applied economics at the University of Georgia.

For his part, Perdue and his team have remained tight-lipped about their specific plans for agriculture, instead maintaining that he will be an advocate for the country’s entire ag industry. He declined an interview through a spokeswoman.

“You are constantly working to make sure that you’ve got the right balance, that you’re doing the right thing for all of agriculture,” said Johanns. “You have to be thoughtful and you have to be careful. You don’t want the next story to be ‘Georgia gets everything, the other 49 states are left out.’”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured