Critics of Ga. immigration enforcement bill write to Facebook, Amazon

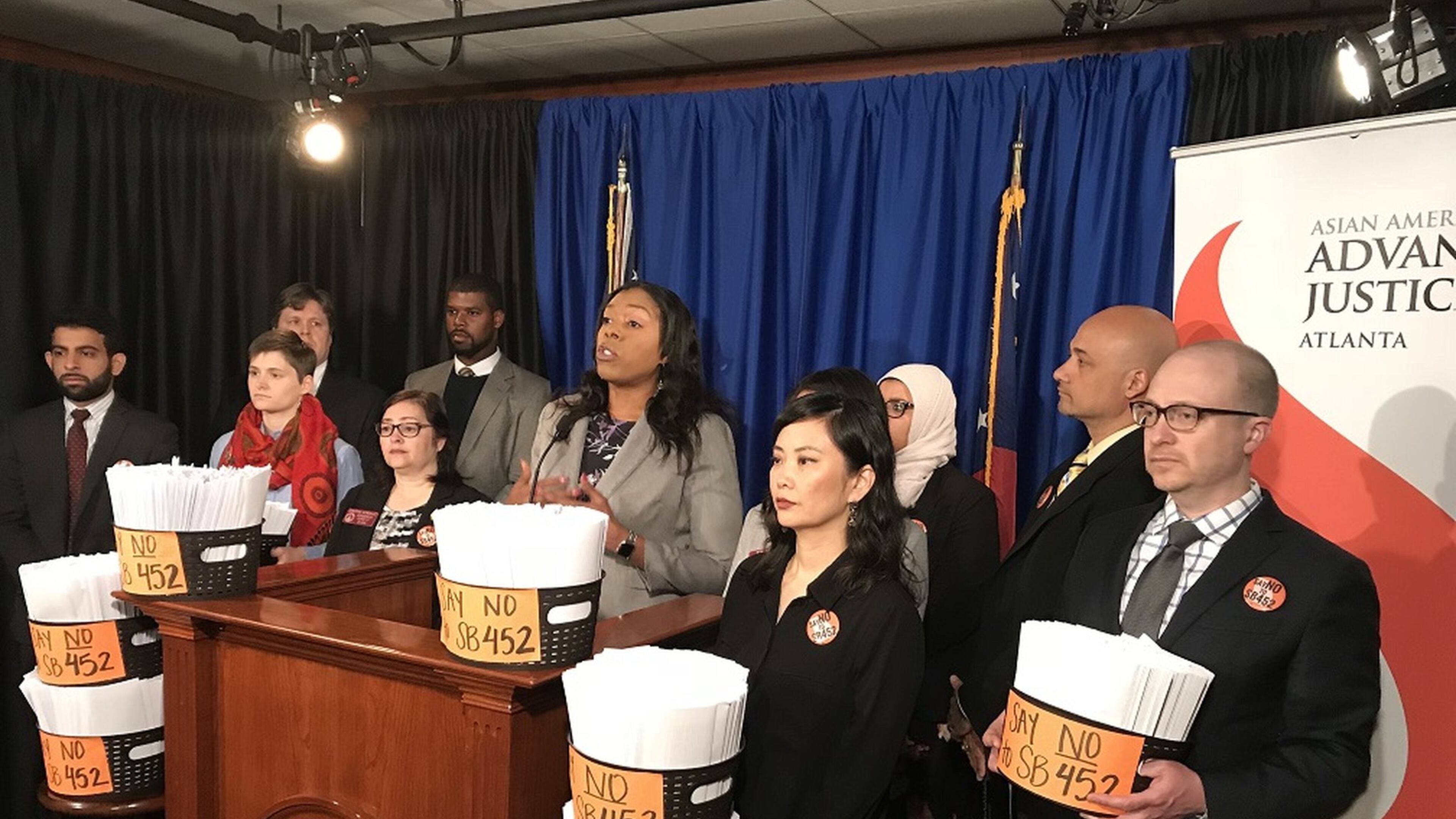

Critics of an immigration enforcement bill backed by Lt. Gov. Casey Cagle have sent an open letter to Facebook and Amazon, detailing objections to the legislation as both companies consider expanding in Georgia.

At issue is Senate Bill 452, which could come up for a crucial vote on the House floor Thursday, the last day of this year’s legislative session.

RELATED: Georgia bill: Police, courts must help with immigration enforcement

House lawmakers are considering a revised version of SB 452 that would require prosecutors to determine whether people facing sentencing in Georgia’s courts are in the country illegally and to notify federal authorities when they are.

The open letter to Facebook and Amazon came from Asian Americans Advancing Justice Atlanta, the ACLU of Georgia, Coalition of Refugee Service Agencies, Georgia Association of Latino Elected Officials, the Georgia and Alabama chapter of American Immigration Lawyers Association and the Georgia NAACP.

"This bill is a clear attempt to surveil, target, harass, and deport immigrant communities," the letter says. "This bill will position Georgia as an unwelcoming state for business, travel, and future immigration."

MORE: Critics blast Georgia immigration enforcement bill backed by Cagle

Facebook and Amazon did not respond to requests for comment Wednesday. This month, Facebook confirmed plans for a sprawling data center campus east of Atlanta, a project expected to employ 100 people in its first phase. Meanwhile, Amazon is eyeing the metro Atlanta area for possible locations for its second headquarters, which could bring a $5 billion campus with as many as 50,000 jobs to the region.

Cagle, who is running for the Republican nomination for governor, released a statement saying it appears critics of SB 452 “are advocating that no person who comes here illegally should ever be deported, even if they commit serious crimes. I disagree strongly, and feel certain most Georgians do too.”

Opponents argue the bill could violate Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures. They point to language in the measure that says unauthorized immigrants “shall be detained, arrested or transported” by local jailers.

House Majority Whip Christian Coomer of Cartersville pushed back against that criticism, pointing to other language in the same paragraph that says: “Nothing in this code section shall be construed to deny a person bond or from being released from confinement when such person is otherwise eligible for release.” He also underscored another part of the same paragraph that says jailers may arrest and detain unauthorized immigrants “as authorized by state and federal law.”

“Nothing in this language requires detention of an inmate beyond the time they would normally be released based on their immigration status,” Coomer said in an email.

SB 452 also says defendants must be brought before a judge, even if the court has a “bond schedule” allowing them to be released on their own recognizance as soon as they are brought to a local jail. Atlanta is the only Georgia city following such a system. It was adopted after reports by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and other news outlets of poor people sitting in jail for weeks or months because they could not afford to post bonds for crimes like begging for money or urinating in public.

In-Depth: Georgia lawmakers take aim at Atlanta’s cash bond ordinance

“The bail language in SB 452 is a shameful attempt to solidify a second-tier justice system for people who have not been convicted of a crime but cannot afford release,” said Marissa McCall Dodson, public policy director for the Southern Center for Human Rights. “Not only is wealth-based incarceration unconstitutional, it is also an inefficient use of local taxpayer dollars to jail people pretrial who do not pose a public safety or flight risk.”

Coomer defended this provision in SB 452.

“If people who are accused of a crime are automatically released on an OR (own recognizance) bond, there is not much to compel them to return to court for their trial,” he said. “If the accused has paid a bond to be released, there is at least some financial incentive for him or her to return for trial. In the alternative, if the accused elects not to return, the local jurisdiction will receive the forfeited bond to help defray some of its costs in processing the accused.”