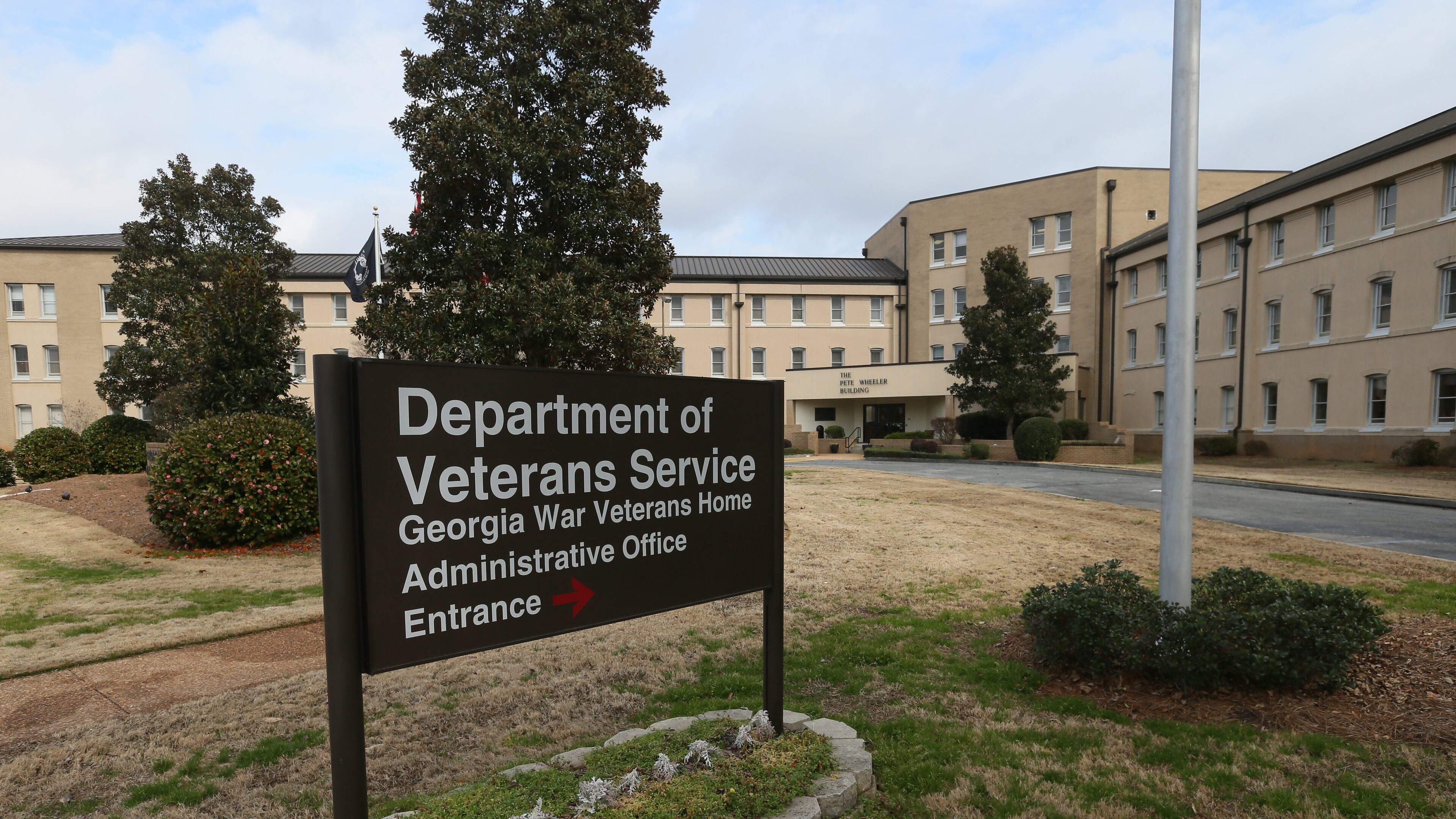

Patient shot himself to death inside Georgia veterans’ home

A patient shot himself to death at the Georgia War Veterans Home in Milledgeville this year, two months before a patient died following a violent confrontation with another resident there, according to records obtained by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Glen Cummings, 64, died by suicide on Feb. 10 in his room at the state nursing home, the records show. Staff members found a handgun in the U.S. Navy veteran’s room after his death.

Cummings' death is documented in Georgia Department of Community Health inspection and Milledgeville police records, and his suicide was confirmed by Baldwin County Chief Deputy Coroner Ken Garland. The records do not say where Cummings got the handgun. Weapons are not permitted in the Georgia Department of Veterans Service home.

“Firearms, knives, weapons, and dangerous items are strictly prohibited in any area of the GWVH campus,” Russell Feagin, director of the Veterans Service Department’s health and memorial division, said in an email. “Any violation of this prohibition may result in the immediate discharge of the patient.”

PruittHealth Veteran Services of Georgia, which operates the nursing home in Milledgeville through a contract with the state agency, said it was “deeply saddened by the unfortunate passing of a truly beloved veteran.”

“The health and safety of our veterans are top priorities at PruittHealth,” the company said in an email.

Another patient, David Tarpley, never got the mental health evaluation he needed for his aggressive behavior before he allegedly beat another resident, Roland Daigle, who died moments later, the AJC previously reported. The April 8 altercation exacerbated Daigle’s heart disease, causing his death, according to state inspection records. His manner of death was listed as homicide.

Inspectors found the nursing home failed to follow state rules for providing mental health services to one of its residents who demonstrated an increase in “aggressive behaviors.” The AJC has found no records of Tarpley being charged with any crimes in connection with Daigle’s death.

Stephen Bradley, the district attorney for the Ocmulgee Judicial Circuit, said officials have reviewed the case “for grand jury and hope to make a decision soon. If it were to be presented, as we expect, then it will be presented in the next few months.”

State inspection records also document an anonymous complaint alleging nursing home staff have neglected patients and put them at risk amid the coronavirus pandemic by moving in and out of isolation areas without personal protective equipment and keeping cleaning supplies locked in a trailer outside.

State inspectors visited the nursing home on July 2 and reported “there were no concerns identified and no deficiencies were cited,” records show. The complaint was not substantiated because of a “lack of sufficient evidence.” Received on June 5, a separate complaint about the possibility that infected employees were bringing COVID-19 into the home also was not substantiated because of a lack of evidence.

COVID-19 has infected 75 patients and killed 18 in the Milledgeville nursing home, state records show, and 75 staff members have tested positive.

Across the nation, state officials are cracking down on nursing homes where many patients have died from COVID-19. This month, for example, New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy announced he would replace the heads of two veterans' memorial homes, where 143 patients and two employees have died from COVID-19.

Georgia’s Veterans Service Department has said its nursing homes in Milledgeville and Augusta are fighting the spread of COVID-19 by limiting access to their buildings, checking the temperatures of visitors, requiring masks and regularly testing staff and patients.

State inspection records also reveal a standalone storage building that held supplies and deliveries for the Milledgeville nursing home was damaged by an electrical fire in January. Repairing the building and replacing its contents cost more than $200,000.

Additionally, a resident at the Milledgeville location complained on March 26 that he could not get help for more than an hour. He also alleged he spotted a staff member sleeping in the nurses' station. The report says the complaint was unsubstantiated because of a lack of evidence; it also says a nurse and a certified nursing assistant were told “breaks need to be taken in the break room, especially if they intend to use the break period to take a nap.” PruittHealth said its employees have not been instructed to sleep in break rooms, saying “that behavior is not aligned with PruittHealth’s Commitment to Caring.”

Cummings' suicide is documented in the Georgia Department of Community Health’s response to an April 22 anonymous complaint. On Feb. 10, a nurse found Cummings in his room at about 6 a.m. He did not act suicidal before his shot himself, the inspection records show. He was “mostly independent,” he signed himself out of the facility daily and he drove his own vehicle to visit family before returning in the evenings. The night before he killed himself, Cummings brought the staff cheesecake and “was in a good mood,” records show. He was last seen at 1:30 a.m. the day he died.

The complaint that mentioned his death was substantiated, though the nursing home was not cited for any regulatory violations.

“Since the resident did not display (any) signs/symptoms of depression or thoughts of suicide, the facility would not have been able to predict this unfortunate event,” the report says.

Cummings' obituary says he was a Warner Robins native who served in the Navy during the Vietnam War era. He was survived by three brothers, three children, a stepdaughter and a grandson.

“Glen,” his obituary says, “lived life to the fullest and made the best of every situation.”