The Atlanta City Detention Center is going to be repurposed and Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms is seeking recommendations for new uses of the jail. Georgia is a pioneer in criminal justice reform, and we commend the city of Atlanta for repurposing its jail.

Some options being considered for the jail include a job training center, a health and wellness center, or a mental health facility. These are great ideas, but why do we have to choose only one?

We propose the city create a multi-use center for adult and youth offenders. This could look like an inpatient rehabilitation program for delinquent youth, with job training, education opportunities, and intervention implementation to create healthy and safe coping skills for both juvenile and adult offenders.

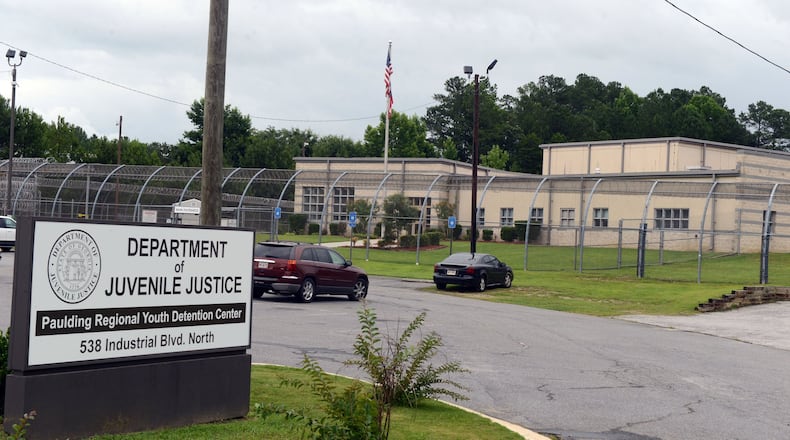

We also challenge Georgians to take this initiative further and reform metro Atlanta’s Regional Youth Detention Center. Earlier this year, San Francisco lawmakers voted to close the city’s juvenile detention center by 2021, in hopes of rehabilitating youth and breaking the cycle of crime. It hopes to create a new program that includes a secure facility, where juveniles are treated like students or clients, instead of being treated like prisoners. The idea is to hold youths accountable for their actions and also create an environment that focuses on changing behavior rather than purely punishing it. San Francisco’s mayor said that children should be in environments that are more like “wellness centers” rather than “a jail or a prison.”

Right now, you may be asking yourself why you should care about reforming juvenile detention centers.

Well, Fulton County’s juvenile crime rates are much higher than the national average, and most juveniles who pass through Georgia’s juvenile justice system will likely return.

Maybe fears will surface about closing the metro detention center. Will we be reintroducing criminals to our community? Will the alternative be successful? How much will it cost?

Repurposing our juvenile detention center may actually make metro Atlanta safer, since many positive results can come from choosing rehabilitation over incarceration. One, there is a decrease in recidivism (tendency for individuals to reoffend). Two, there is a lower crime rate for people diverted from the prison system. Three, it helps the youth, rather than harming them. Four, it is more cost-effective to help youth rather than imprison them.

Incarcerating youth in juvenile secure facilities negatively impacts children’s future employment, mental and physical development, and education. Children taken out of their communities and placed in highly restrictive environments are not able to obtain the relationships and experiences required for healthy development. This disruption in healthy development increases isolating and antisocial behaviors in children who are locked up, making them more likely to re-commit crimes.

When youth are imprisoned, they are basically going to a state-run facility to learn from others who have trespassed the law, says Shankar Vedantam, NPR’s host of Hidden Brain. Youth who’ve been incarcerated have an increased likelihood of recidivism.

Are these kids learning to respect the law, or are they learning to be better criminals? This is a question we must ask when considering whether to keep juvenile halls.

The Atlanta Police Foundation has taken on the challenge of reducing juvenile crime with the help of the At-Promise Center. At-Promise focuses on diverting youths with misdemeanors away from detention centers, intervening to address behavior, and helping prevent future crime through education and personal growth. The program is in its second year and is showing greatly improved outcomes — participants show recidivism rates of between 2 percent and 4 percent.

But what about youths who require placement in secure facilities?

These children are placed in detention centers and secure campuses throughout the state. Not only are these facilities ineffective, they have also been shown to cause great harm. Like adult jails and prisons, there are also concerns for inmate safety in juvenile secure facilities. Children locked in these facilities are at an increased risk of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, both by other inmates and corrections staff..

In Georgia, officials say it costs $90,000 per incarcerated juvenile each year, and according to the Georgia Department of Juvenile Justice, the 2019 state budget for secure detention centers is $128.8 million. Why do we spend so much money on facilities that do not work?

Although it’s difficult to admit, we are not helping juveniles prepare for successful reentry after incarceration, we are actually hardening juveniles and psychologically preparing them for the realities of life as an incarcerated adult.

If these secure detention facilities are ineffective, harmful, and costly, how do we accommodate children who have committed crimes and need a structured and supervised environment? There must be an alternative to using cages for intervention; after all, they are only children.

We propose, for example, that the city create a multi-use center that provides job training, mental health services, and resources for successful reintegration and prevention of future crime for adult and juvenile populations, with a secure wing for juvenile housing and rehabilitation. Although centers like this are costly upfront, they save money in the long run by reducing juvenile crime and keeping more juveniles from becoming adults in the prison system. Promoting smarter decarceration creates a safer community for us all.

Stephanie M. Hawkins, from Griffin, is in the Master of Social Work degree program at the University of Southern California (USC). She has worked as a missionary in three countries with children and their families who live in poverty or have been displaced. Christina Dal Pozzo is in the same program at USC. She’s worked as a forensic interviewer and lab director at the USC Child Interviewing Lab, where she interviewed 60 children about sexual abuse cases.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured