Frederic Bastiat, a French economist and member of the French National Assembly, lived from 1801 to 1850. He had great admiration for our country, except for our two faults — slavery and tariffs. He said: “Look at the United States. There is no country in the world where the law is kept more within its proper domain: the protection of every person’s liberty and property.” If Bastiat were alive today, he would not have that same level of admiration. The U.S. has become what he fought against for most of his short life.

Bastiat observed that “when plunder becomes a way of life for a group of men in a society, over the course of time they create for themselves a legal system that authorizes it and a moral code that glorifies it.” You might ask, “What did Bastiat mean by ‘plunder’?” Plunder is when someone forcibly takes the property of another. That’s private plunder. What he truly railed against was legalized plunder, and he told us how to identify it. He said: “See if the law takes from some persons what belongs to them, and gives it to other persons to whom it does not belong. See if the law benefits one citizen at the expense of another by doing what the citizen himself cannot do without committing a crime.”

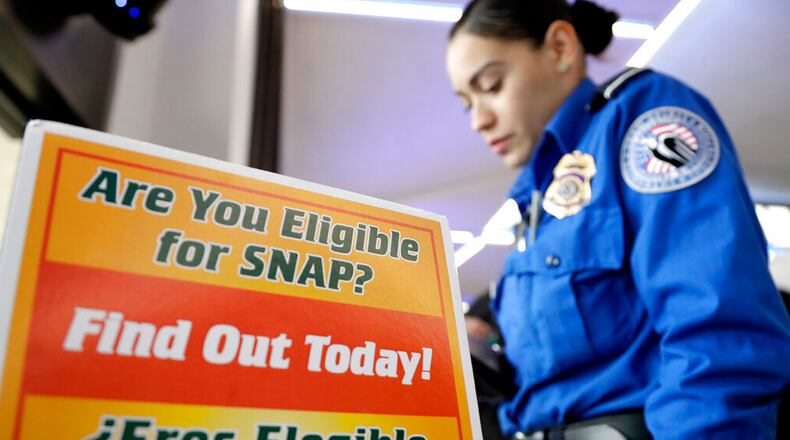

That could describe today’s American laws. We enthusiastically demand that the U.S. Congress forcibly use one American to serve the purposes of another American. You say: “Williams, that’s insulting. It’s no less than saying that we Americans support a form of slavery!” What then should we call it when two-thirds to three-quarters of a $4 trillion-plus federal budget can be described as Congress taking the property of one American and giving it to another to whom it does not belong? Where do you think Congress gets the billions upon billions of dollars for business and farmer handouts? What about the billions handed out for Medicare, Medicaid, food stamps, housing allowances and thousands of other handouts? There’s no Santa Claus or tooth fairy giving Congress the money, and members of Congress are not spending their own money. The only way Congress can give one American $1 is to first take it from another American.

What if I privately took the property of one American to give to another American to help him out? I’m guessing and hoping you’d call it theft and seek to jail me. When Congress does the same thing, it’s still theft. The only difference is that it’s legalized theft. However, legality alone does not establish morality. Slavery was legal; was it moral? Nazi, Stalinist and Maoist purges were legal, but were they moral?

Some argue that Congress gets its authority to bypass its enumerated powers from the general welfare clause. There are a host of proofs that the Framers had no such intention. James Madison, the “Father of the Constitution,” wrote, “If Congress can do whatever in their discretion can be done by money, and will promote the general welfare, the Government is no longer a limited one possessing enumerated powers, but an indefinite one.” Thomas Jefferson wrote, “Our tenet ever was … that Congress had not unlimited powers to provide for the general welfare, but were restrained to those specifically enumerated.” Rep. William Drayton of South Carolina asked in 1828, “If Congress can determine what constitutes the general welfare and can appropriate money for its advancement, where is the limitation to carrying into execution whatever can be effected by money?”

What about our nation’s future? Alexis de Tocqueville is said to have predicted, “The American republic will endure until the day Congress discovers that it can bribe the public with the public’s money.” We long ago began ignoring Bastiat’s warning when the federal government was just a tiny fraction of gross domestic product — three percent, as opposed to today’s 20 percent: “If you don’t take care, what begins by being an exception tends to become general, to multiply itself, and to develop into a veritable system.”

Moral Americans are increasingly confronted with Bastiat’s dilemma: “When law and morality contradict each other, the citizen has the cruel alternative of either losing his moral sense or losing his respect for the law.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured