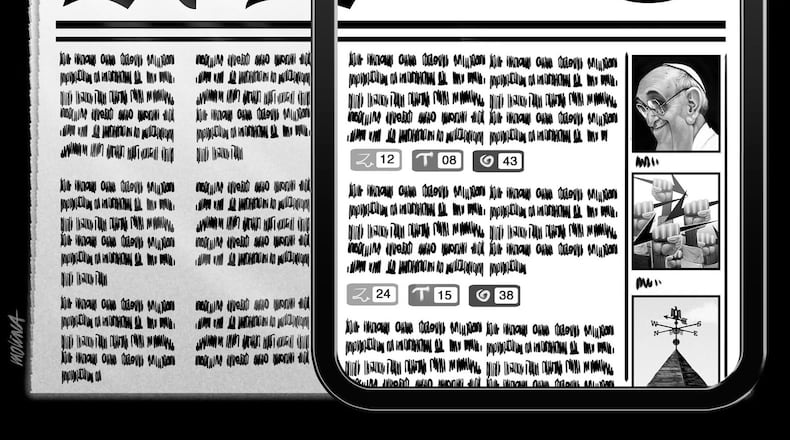

For more than a century, folks in Ware County unfolded The Waycross Journal-Herald to catch up on the births, deaths and everything that happened in between.

They could keep up with local high school scores, the latest speaker at the Kiwanis and whose son made Eagle Scout. They could see what county commissioners and city council members were up to. Now and then, they even read about their representatives in Atlanta and Washington.

Small stories add up to a real place; the Journal-Herald reminded folks who they were, where they had been and where they were going. Its pages held a community with thousands of opinions uttered in a shared voice.

That voice has fallen silent.

On Sept. 30, the family-owned newspaper printed its final edition. Roger Williams, the publisher and founder’s grandson, said he had no other choice. The paper had become a financial threat to his family, including his brother, Jack Williams III, the paper’s editor.

The Journal-Herald was eaten alive by the same pernicious forces that threaten all newspapers – including the AJC.

Ware County is the 29th county in Georgia to lose its newspaper. The silence now fills nearly a fifth of Georgia’s counties.

In news deserts, reporters no longer cover school boards, county politicians or zoning committees. No one gathers and reviews local crime reports. Judges sit on benches without the familiar sight of a reporter taking notes and creating a peoples’ record. The high school play goes unnoticed. No clips to stick proudly on the refrigerator door. Obits, births, marriages – who takes note of these?

The crooked, comfortable and cronies who always found local newspapers a nuisance can celebrate their demise. The hen house goes unwatched.

I cherish community newspapers. I began at a tiny weekly in Fayette County 40 years ago, covering ribbon cuttings, the Fayette County Tigers and the school board - as well as Halloween fairs, the cop shop and whatever else I could stuff in my notebook. I’ve never done more meaningful work. That paper is long gone. I’m not sure what I would do without The Brunswick News.

On the Journal-Herald’s website, a bright red box lists the too-familiar causes of death.

“Facebook, websites, data streaming, ‘marriage mail,’ TV, radio, and several other mediums, followed by reduced print subscriptions as Americans and Waycrossans turned to cell phones to get their news.”

(“Marriage mail” is the odd name for mass-mailed flyers that once filled papers like the Journal-Herald.)

Democracy also died a little on Sept. 30.

When the founding fathers designed our government, they assumed a healthy free press would persist. “The basis of our governments being the opinion of the people, the very first object should be to keep that right,” wrote Thomas Jefferson. “Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

It’s worth nothing that the free press is the only foundational institution of American democracy that was left to fend in the free market. For two centuries, that was just fine. Newspapers survived waves of threats including vindictive politicians, radio and television. Then came the Internet. Then smartphones. Then social media.

On the Friday before shutting down, Williams met with what was left of his staff. “We told them what the situation was,” he told The Brunswick News. “I hate it, but we didn’t have any recourse.’’

It was more than closing a business. “You feel like you’re losing a part of yourself,’’ he said. “I’m a Christian. I pray about it. The Lord will help you get through it.”

A miracle is indeed in order.

Rick Head, the paper’s sports writer, is working to create one. He purchased the Journal-Herald’s nameplate and subscriber list and intends to reintroduce it as a weekly that doubles down on being local. National news is everywhere; Ware County isn’t.

“Several employees approached me to consider buying the business,” Head told me. He already owns a weekly in neighboring Brantley County.

Maybe he can conjure a glimmer from a landscape of gloom. More than 170 counties across the country no longer have a local newspaper.

This is more than nostalgia: The disintegration of community journalism contributes to the polarization tearing at our country. It lowers voter turnout, reduces government accountability and leads to less trust.

The loss in the South is breathtaking. Since 2004, more than 90 weeklies and dailies have folded across the poorest and least educated part of America. This dwarfs the losses in other regions – the next worse, the Mountain Region, lost 29 newspapers, the same as the state of Georgia alone.

“The stakes are high,” a group of researchers at the University of North Carolina wrote. “Our sense of community and our trust in democracy at all levels suffer when journalism is lost or diminished. In an age of fake news and divisive politics, the fate of communities across the country — and of grassroots democracy itself — is linked to the vitality of local journalism.”

Folks in news deserts can stll communicate, at least the ones with computers or data plans. Facebook and other social media slither hungrily into the void.

But it’s not the same. I don’t care what they all say about “citizen journalism.” The heavy lifting of democracy requires trained reporters and editors.

The AJC remains a mighty engine for reporting on state politics and policies as well as providing deep investigations. But who’s watching the hundreds of politicians, police chiefs and bureaucrats in the rest of the state?

Maybe digital is the answer. In recent years, as many as 200 state and community sites have been launched across the country – many are nonprofits funded by philanthropy. The online-only Texas Tribune has filled the state government space well in Texas. Others show promise, including MinnPost, Florida Bulldog, Maryland Matters.

Most of these startups are focused on watchdog and investigative journalism. Some have an obvious political bias – preaching to the choir as its niches.

Watchdog reporting is important stuff, but it isn’t the same as reading about volunteers tidying a local river, the hunt for a speeder who tried to pass a school bus or the opening of a teen recreation center.

Can anyone ever pull it all together into something like a newspaper?

Rick Head is working on his miracle in Waycross.

“The support from the community of the announcement of me buying the publication has been surreal,” he said. “I’m very humbled and excited.”

Local news could use a bloom in the desert.

Bert Roughton Jr. is the retired senior managing editor and editorial director for the AJC. He can be reached at ajcbroughton@gmail.com.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured