City Hall — and the billionaires and millionaires it collaborates with — is obsessed with mega-projects such as the Falcons stadium, the failed 2012 transportation referendum and the under-ridden streetcar at the expense of Atlanta neighborhood development. It fails to understand Atlanta’s greatness is a product of its beautiful and vibrant neighborhoods, not just its corporate edifices.

The most neglected of these Atlanta neighborhoods are predominately African-American. Not only have these neighborhoods been neglected, they have been assaulted by the public and corporate sectors that have profited from their decline and underdevelopment. They have been victimized by predatory lending, redlining, reverse redlining, mortgage fraud, massive foreclosures and, most recently, investment land banking.

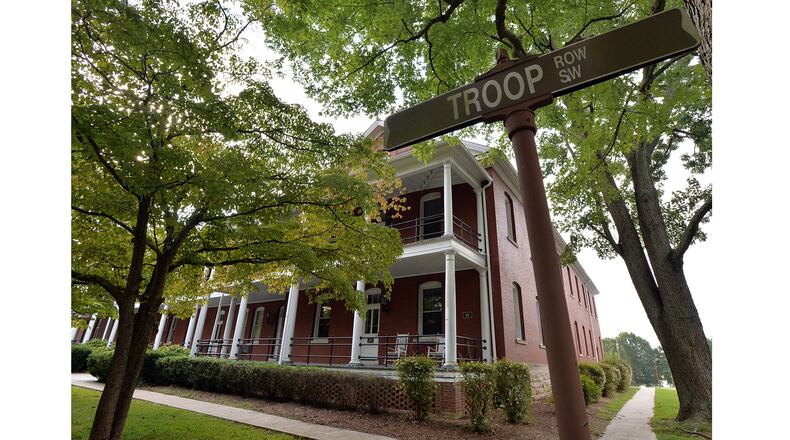

The neighborhoods around Fort McPherson are an example of this. After the decision was made to close the fort, the planning effort to redevelop the 488-acre site began in earnest. The McPherson Redevelopment Authority produced a plan that called for a mixed-use development with a biomedical facility as its centerpiece.

In addition, a community initiative staffed by Georgia Tech faculty and students produced a community-benefits plan that envisioned a development that would integrate the base into the community and hire and train people from nearby high-unemployment neighborhoods, among other things.

When one movie company proposed bringing an 80-acre studio to the base, it was told no negotiations could go forward until the authority had control of the base.

All these efforts came to naught when Mayor Kasim Reed issued an off-the-shelf edict that 330 of Fort Mac’s acres would be sold to a different movie producer — “Madea” creator Tyler Perry — for $30 million. With a net worth of $400 million, Perry was set to move his studios in Atlanta’s Greenbriar neighborhood outside the city when Reed secretly intervened to offer Perry the Fort McPherson property.

Indeed, so much of the Perry deal has been done in secret backroom dealing, I had to appeal to the attorney general to try get the McPherson authority to be transparent and open.

Perry has had a checkered relationship with the neighborhoods where his studios have been located. In Inman Park, when Perry built studios, the neighbors objected to his doing so without permits or plans, and work was stopped. Since his studios have moved to the Greenbriar area, there has been no obvious positive impact on that community. While the details of Perry’s plans for Fort McPherson remain shrouded in mystery, it is clear he intends to wall his acreage off from the community — to build a fort within a fort.

The redevelopment authority has made unsubstantiated statements about projections of added jobs Perry’s studio would produce, but he has made no commitment to hire and train residents from contiguous neighborhoods. Even the Atlanta Olympic Committee agreed to a training and job program for neighborhood residents for the Olympic stadium construction in the 1990s.

Tyler is getting the sweetest of sweetheart deals. Why? He is a friend of the mayor’s, and one of Reed’s college buddies happens to be Perry’s agent. About the time Perry contributed more than $7,000 to Gov. Nathan Deal’s reelection, the state withdrew its plan for a training facility at the fort. While the state was going to pay $10 million for 20 acres at $500,000 per acre, Perry is getting his 330 acres at $90,000 per. While the authority has a right of first refusal if Perry sells any of the property he purchases, the authority will only be able to purchase at market rates.

The coup de grace was Reed’s last-minute presentation of a proposal for the city to put taxpayers on the hook for a $13 million line of credit to do the Perry deal. Reed demanded the proposal pass the same day it was unveiled, and a docile City Council complied. These deals smack of cronyism and corruption.

The city’s neighborhoods need better from Reed and City Hall. It is not difficult to see the Perry deal will maintain underdevelopment and intensify gentrification in southwest Atlanta neighborhoods.

There are alternatives to this trickle-down redevelopment that never seems to trickle down to all of Atlanta’s neighborhoods. The Pryor Road area is an example: In an area that faced many challenges, you now have single-family subdivisions, mixed-income developments, condominiums, a YMCA, a Major League Baseball youth facility, and senior citizen housing.

Along with Turner Field, the Fort McPherson redevelopment will determine the long-term fate of many of Atlanta’s neglected neighborhoods.

State Sen. Vincent Fort, D-Atlanta, represents the 39th district.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured