The freedom fighter: How Atlanta’s C.T. Vivian changed history

It was cold and rainy in Selma the morning of Feb. 15, 1965, as C.T. Vivian rose early and carefully selected his wardrobe for the day: a dark suit and collared shirt.

Instead of a tie, he wrapped a scarf around his neck. He slipped on a pair of freshly shined shoes and his tweed overcoat. He decided against a hat — even though that was the custom in the 1960s. In a time of conflict, Vivian knew, hats got lost.

Respectability was woven into the nonviolence doctrine that Martin Luther King Jr. preached, and few practiced nonviolence as efficiently as the handsome, tall, slender and well-versed Vivian. That hadn’t always been the case. Growing up as one of only a few blacks in a small Midwestern town, Vivian brawled almost every day in the schoolyard.

Now both a minister and a leader in nonviolent protest, Vivian was about to face the biggest test of his religious and political beliefs.

On this day, he walked to Brown Chapel AME Church, a Romanesque Revival red brick church with two steeples that had become a safe haven for civil rights workers to sing, gather and pray.

If Alabama was the front line of American segregation, Selma, where 28,000 blacks were not registered to vote, was ground zero. Southern to the core, Selma enforced a strict form of oppression.

And the chief enforcer was Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark, a 6-foot-2, 220-pound bruiser known for a short temper, a fondness for cattle prods and wearing a George Patton-inspired World War II helmet.

Two weeks earlier, the local Selma paper ran a front page photo — carried nationally — of Clark beating Annie Lee Cooper, a 54-year-old black woman, on the sidewalk outside of the courthouse as she tried to register to vote.

Clark had initially poked Cooper in the back of the neck with his cattle prod, so Cooper turned and punched Clark in the face. Deputies dragged her to the ground as Clark savagely beat her with the prod. Vivian himself had a confrontation with Clark 10 days earlier.

“He was a mean, vicious, sick man,” recalled John Lewis.

At the church, Vivian greeted the crowd by asking if they remembered to be nonviolent — no weapons or fighting — even if they were beaten. They quietly nodded yes.

Vivian smiled and pulled the collar of his overcoat over his freezing ears and led them through the heart of downtown. They made a left on Lauderdale Street and arrived at the steps of the Dallas County Courthouse. Sheriff Clark was waiting.

2. Learning nonviolence

In grade school pictures, Vivian is the only black boy in a sea of overall-clad white kids. He lived with his grandmother in the small town of Macomb in western Illinois. His grandmother, Annie Woods Tindell, chose the place because it was home to Western Illinois University, and she wanted her grandson to go to college, a privilege no one in the family had ever had.

Vivian’s mother and father divorced when he was a youngster growing up in Missouri, and Annie took a keen interest in her grandson’s education.

She often read to him passages from Williams Wells Brown’s “The Black Man: His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements,” which was published in 1863 — two years before the 13th Amendment abolished slavery in America.

As outlined in Wells’ introduction, the book traced the lives of men who had, through “genius, capacity, and intellectual development, surmounted the many obstacles which slavery and prejudice have thrown in their way,” and “raised themselves to positions of honor and influence.”

The first time Annie showed Vivian the book, his jaw dropped.

“She said, ‘These are Race Men. Men of mark.’ They had made their mark in life in spite of racism and poverty,” Vivian said. “This book has always been a part of my life. She didn’t say, ‘You gonna do this,’ and I didn’t say anything back to her. She said it and moved on.

“But I knew.”

Pampered at home as the only child he was, Vivivan dressed well and was good looking. While popular in Macomb, he was not always socially accepted. “Racism was always there on the edge,” he said.

He would hear about parties, then be told by his white friends that their parents wouldn’t let them invite him. He lost the lead in a school performance because, he was told, it was a family play. Instead, he had to paint sets.

“That is a long way from the lead,” Vivian said. “But that gave me an understanding of the difference in how I thought things were, and what they actually were.”

Some slights he could not forgive, so he settled them with his fists. He was an easy target. He wore nice clothes and was black. But Vivian said most of the fights were just Depression kids acting out the only way they knew how.

“All we did was fight each other,” Vivian said. “It was not because we were black or white, because we were all poor. We just fought.”

Sometimes, he was the victim. Once a group of boys chased him to the back of a lumber yard. Cornered and figuring he couldn’t beat them all, he challenged the leader, Theodore, to a fight. Theodore refused and they all backed down.

Vivian never ran again.

Sometimes, he was the aggressor. Like the time he grew tired of a bully beating up weaker kids, so Vivian beat him up.

“We fought each other up and down that alley until we got tired,” Vivian said.

He was never bullied again.

Finally, he became the bigger person.

In the fourth grade, a white boy gave him a racist Valentine’s Day card featuring a stereotypical black image. Furious, Vivian followed him to the lumber yard.

“I pushed him. I hit him. But he wouldn’t fight me,” Vivian said. “If he wasn’t going to fight me, I couldn’t fight him. I wanted to fight, but I couldn’t. That is when I first learned nonviolence.”

3. Leading a movement

Vivian left Illinois in 1955 and moved to Nashville to study religion at the historically black American Baptist College. After high school, he fulfilled his grandmother’s wishes and enrolled in Western Illinois, majoring in English. But he was barred from joining the prestigious English Club by the adviser and quickly became disillusioned with the university.

By the time he reached Nashville, Vivian was already a husband, father and experienced civil rights advocate. He participated in his first sit-in in Peoria, Ill., in 1947, nearly a decade before the Montgomery bus boycotts and well before King burst upon the stage.

A local restaurant was refusing to serve blacks. The sit-in ended the discriminatory policy.

“I knew then that we would always be working to end segregation and racism,” he said.

Nashville in the late 1950s became the training ground for non-violent protest, thanks to a Methodist minister and Ghandi follower named Jim Lawson.

Along with Kelly Miller Smith, Lawson and Vivian formed the Nashville Christian Leadership Conference, the first affiliate of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Like Atlanta, Nashville was teeming with black colleges such as American Baptist, Fisk, Meharry and Tennessee State, which produced a class of civil rights leaders that included John Lewis, Diane Nash, James Bevel and Bernard Lafayette.

With the students on board, Lawson began a series of weekly workshops in black churches to discuss ways to desegregate Nashville through direct action, which would include sit-ins, picketing, economic boycotts and the possibility of jail.

Older than most of the others, Vivian was a student of Lawson, but also a key mentor to younger students because of his age, experience and unique intellectual interpretation of nonviolence.

Vivian became so committed to nonviolence that he wouldn’t even allow his children to watch “The Three Stooges,” according to his daughter.

Vivian drew others to him another way: He was a skilled and gifted orator. Indeed, King himself later called Vivian the “greatest preacher that ever lived.”

In 1961, as they continued to train, the Nashville group watched closely as a group of civil rights workers from the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE), started Freedom Rides, to challenge interstate transportation laws. When they abandoned the rides after a series of vicious attacks in Alabama, the Nashville group, including Vivian, continued through the treacherous Deep South.

Those rides, which led to Vivian being arrested and shipped to Mississippi’s notorious Parchman Prison, marked the beginning of his major national movement work.

Andrew Young said because Vivian was from the Midwest and had grown up with whites — unlike most of the Southern leaders — he brought a different perspective to SCLC.

“He was always free of any ego or any attempt to self-serve. He was totally unselfish in a movement that had a bunch of big egos,” Young said. “He was comfortable working with and being around white people. He was not intimidated.”

Vivian was also strongly influenced by events in his personal life. His first son and third child, Cordy Jr., was born in 1955 with cerebral palsy.

Doctors initially refused to place the prematurely-born Cordy in an incubator, because they didn’t have one for black babies.

“Daddy always believed that that contributed to Cordy’s condition,” said Denise Morse, Vivian’s daughter.

Cordy had limited use of his arms and legs his whole life. Until he was able to walk on his own, his parents literally carried him to school.

Cordy had a rocking horse that he played on until he fell asleep.

It was when Cordy was asleep that the pain was the most intense — for everyone. Doctors fitted his leg with a steel brace in an effort to straighten it. At night, Vivian often walked into the darkness of his son’s room and saw him squirming and crying in pain.

His trademark smile disappears and his eyes fill with tears when he recalls those moments.

“I just wanted to snatch that thing off him and stop the pain,” Vivian said. “But I knew if he grew up not being able to walk, he would know that I should have allowed the suffering.”

Vivian turned Cordy’s ordeal into a parable for the civil rights movement.

“C.T. would tell us that story about how painful that was for him,” Young said. “If the South is gonna rise and walk again, we had to keep the pressure on, because racism was a sickness only we can heal. It was the perfect analogy of what we did in the South to keep the pressure on.”

4. Selma, 1965

Vivian and his 40 marchers arrived at the Selma courthouse and found Clark standing at the top of the steps, surrounded by a phalanx of deputies. TV news crews waited to capture the tense moment.

It was Vivian, the SCLC’s national director of affiliates, who had convinced the group that Selma’s black community was savvy enough to start a major campaign, said Pulitzer Prize-winner David Garrow, author of “Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.”

Several different groups — teachers, housekeepers, students — had made unsuccessful attempts to register to vote. That cold February day in 1965 was not Vivian’s first time confronting Clark. On Feb. 5, he made an earlier trip, where he was greeted by a helmeted Clark, who allowed him to pray before arresting him.

This time, Vivian walked up the steps, telling his familiar adversary the marchers had come to register to vote. Clark refused to let them pass, saying the courthouse was closed, and forced them to stand in the rain.

“Whenever anyone does not have the right to vote, then every man is hurt,” Vivian told Clark, adding that the only reason he remained an elected sheriff was because he refused to allow blacks to vote. “You don’t want them to register because you would no longer be able to use your brutality on them.”

Clark turned his back on Vivian, who was quick to use the slight to his advantage.

“You can turn your back on me, but you cannot turn your back on the idea of justice. You can turn your back now and you can keep the club in your hand, but you cannot beat down justice,” Vivian said.

By now, a crowd of whites started to heckle Vivian, calling him, of all things, a screwball.

“I’m a screwball for the rights of people to vote and if this is the kind of screwball I am, this is the kind of screwball America needs,” he told them. “The kind of screwball that can get rid of Sheriff Clark, who beats people on the streets and keeps people from registering to vote.”

The growing crowd mocked Vivian, who continued to lecture them.

“You’re laughing because you don’t know what else to do. There was a day when you would beat me instead of laugh, wouldn’t you?” Vivian said, before turning back to Clark.

“There was a day when you would arrest everybody and say, ‘Well, we took care of that.’ But the day of your criminal activity is just about over, gentleman, and you’re going to have to survive by the means of law and order.”

Clark got madder, but didn’t say a word. So Vivian talked around him and addressed the deputies.

“We want you to know, gentlemen, that every one of you, we know your badge numbers, we know your names,” Vivian told the deputies, comparing their actions to Nazi Germany.

Clark finally spoke, asking Vivian if he lived in Dallas County. Vivian said no, but he represented county residents who could not vote. Vivian turned and faced the crowd, taking them to church with a call and response.

“Is what I am saying true?” he yelled.

“Yeah!” the crowd responded.

“Is it what you think and what you believe?” Vivian asked.

“Yeah!” they shouted.

Clark finally snapped.

He ordered the TV cameramen to turn off their cameras.

“If you don’t turn that light out I’m gonna shoot it out,” Clark barked.

The deputies started pushing the marchers down the stairs, as Vivian pleaded to them not to beat them.

Clark then punched Vivian square in the face with a vicious left jab, sending him sprawling down the courthouse steps.

As he tumbled down the stairs, a million things were going through his head — school fights, sit-ins, Parchman Prison, Cordy, the chance he might be killed. The marchers who had come with him screamed and began to scatter. Some started to run back to Brown Chapel. Vivian lay dazed for a moment, his head throbbing and blood streaming down his face.

The smartest thing, Vivian knew, was to stay on the ground. But he knew he had to get up.

“I had to show that I wasn’t afraid.”

Vivian got up, but he didn’t know what to say. Yet he never stopped talking. His voice now higher and more urgent.

“If you gonna arrest us, arrest us. But you don’t have to beat us. If we are wrong, why don’t you arrest us? We’re willing to be beaten for democracy. And you misuse democracy in the street. You beat people bloody in order that they don’t have the privilege to vote. You beat me in the side and then hide your blows,” shouted Vivian, before quoting Winston Churchill. “What kind of people do they think we are? What kind of people are you? We are willing to die for democracy!”

Because it was carried on television, historians have called Clark’s attack on Vivian one of the defining moments of the civil rights movement.

“He knew it was gonna advance the movement the instant it happened,” said Taylor Branch, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of several histories of the civil rights movement.

Bruised and wet, Vivian said he was never tempted to fight back. Nonviolence had to mean something, he said.

“It was not about me,” Vivian said. “It was about, does it give us a chance to get rid of an evil system and evil people that run it. You have to confront the evils that are destroying people. And stop it.”

Clark later said he didn’t realize that he had punched Vivian until his doctor told him he had a fractured finger.

He would be voted out of office a year later and eventually serve time in prison for drug smuggling. Vivian left SCLC a year later as well, focusing on other projects — including starting the Upward Bound college prep program — before coming back in 2012 to become the organization’s president.

“The thing about it is he didn’t have to do it,” Young said. “There had been people going down there every day and getting turned back by Jim Clark who just walked away. No one gave C.T. any instructions to do that. It took a lot of courage to get in Jim Clark’s face. But if he had not taken that blow in Selma, we would not have had the Voting Rights Act.”

5. At the White House, 2013

C.T. Vivian woke up early on the morning of Nov. 20.

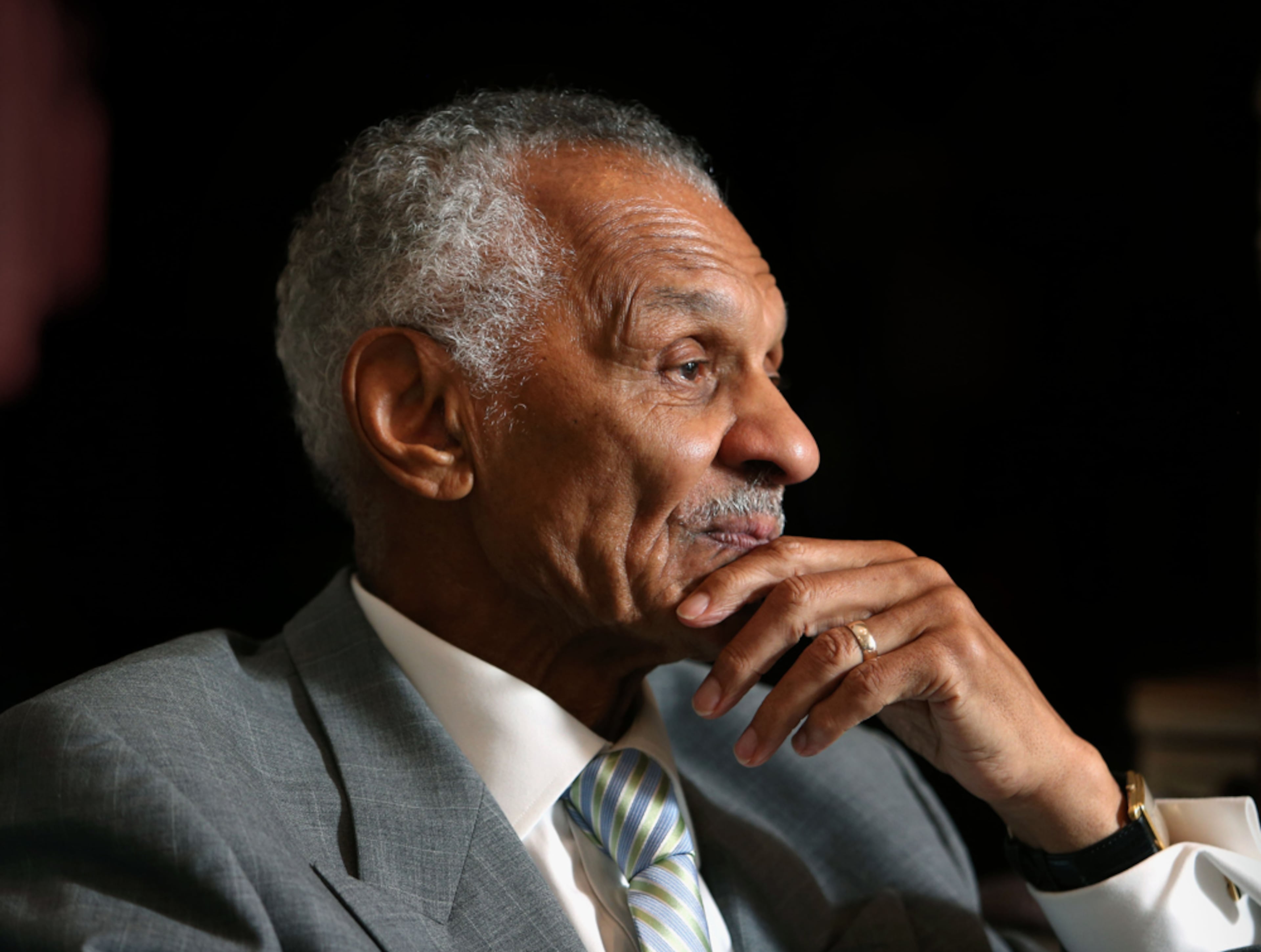

It was cold, but sunny in Washington, D.C., as the 89-year-old dressed.

He slipped on a pair of freshly shined black wing tips. He wore a red tie, a crisp white shirt with cuff links and a dark blue suit. He put on his overcoat, but no hat.

Vivian’s hair is gray now, but aside from a few wrinkles, he looks almost exactly as he did that cold morning in Selma 48 years ago.

When Vivian gets excited and wrapped up in a joke or one of his long stories, his voice gets so high and fast that you can barely piece together what he is saying. The punch line almost always comes with him slapping his thigh and calling his listener “Doc.”

His daughter, said “Doc” actually comes from her father not being able to remember names in the spur of the moment — even those of his seven children, all of whom he called “little stuff.”

A town car took him on a journey to the White House, where the country’s first black President, Barack Obama, was waiting to give him and 15 others the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor.

Each recipient got five tickets for guests, but Vivian was able to score a sixth for his children.

There were two notable absences: his wife, Octavia, and Cordy.

Cordy died on Jan. 30, 2010, of heart failure. He had studied three years at Clark College and worked for a while at Emory University, but never seemed fulfilled.

“After Cordy’s funeral, mom and dad sat in their bedroom and sobbed together,” Morse said. “They went through so much with him.”

A year later, after 58 years of marriage, Octavia died.

“She was sick and he said, ‘I am not ready,’ Morse said. “Up to the end, he couldn’t let go.”

“I wish my wife was there with me,” Vivian said later. “But life didn’t read that way for us.”

In the White House’s ornate East Room, Vivian sat on Obama’s left, while the president commanded the podium. To Vivian’s left was Patricia McGowan Wald, the first woman appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. To her left was Oprah Winfrey.

Also on stage were former President Bill Clinton, feminist Gloria Steinem, Mr. Chicago Cub Ernie Banks, musician Arturo Sandoval and country singer Loretta Lynn, among others.

“Time and again, Rev. Vivian was among the first to be in the action,” Obama said. “And at 89 years old, Rev. Vivian is still out there, still in the action, pushing us closer to our founding ideals.”

When it was time for him to get his medal, a military aide read Vivian’s bio. He stood nervously with his right hand resting across his stomach and his left hand touching his face.

Obama, who was 3 years old when the events at Selma happened, walked behind Vivian and placed the medal around his neck.

Vivian smiled. Then he laughed. Then he hugged Obama, remembering to call him Mr. President, instead of Doc.

“Did we win? Did we change the law? Did we open institutions? Did we help somebody?” Vivian said later. “There wasn’t an institution in America that wasn’t changed by what we did. But the victory isn’t completely won yet. We still have to save America. Black people have to save America. It can’t save itself. Four hundred years of slavery has proven that.”

HOW WE GOT THE STORY

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s bright light in Atlanta had the unintended consequence of blinding history to the substantial contributions of many others who played pivotal roles in the civil rights movement. Last month, President Obama recognized C.T. Vivian, one of Dr. King’s lieutenants, with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Today, AJC reporter Ernie Suggs recounts Vivian’s historic contribution to American history. Drawing on a wealth of sources, Suggs interviewed surviving luminaries of the movement such as John Lewis and Andrew Young, both former Medal of Freedom winners, and spent hours with Vivian in his Atlanta home. He also interviewed family members and historians, and traveled to Washington last month to observe Vivian receive the Medal of Freedom. He obtained historical footage of Vivian in action and was given access to oral interviews that Vivian did with The Smithsonian Institute’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Suggs’ gripping, insightful reporting is the quality journalism AJC readers expect on such an important figure in American history.

Ken Foskett

Assistant Managing Editor